The translation of Neapolitan mafia nicknames in the TV series Gomorra into English and Spanish

Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain

Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain

ABSTRACT

This study deals with the translation for subtitling and dubbing of a type of Italian expressions called contronomi, which refer to the nicknames traditionally used by members of the Neapolitan mafia. We have focused on this special kind of nickname used in the Italian series Gomorra to identify and describe the techniques employed in the translation of these meaningful linguistic cultural elements found in the series into English and Spanish. To this end, a contrastive analysis of the source text in the Neapolitan dialect and the subtitled version in English and the dubbed version in Spanish of the first season has been carried out. The results obtained showed that the translation tendencies regarding the handling of the contronomi of the main and secondary characters of this audiovisual product greatly differ in the two target languages and cultures. While the English version tends to make them understandable to its target audience, the Spanish version favours keeping them in their original form as if they were proper names.

Keywords: audiovisual translation; dubbing; subtitling; translation technique; nickname; contronome.

I. INTRODUCTION

Technological development has contributed to the growing global consumption of audiovisual products from different countries, in a wide range of genres and through various channels. From the most traditional genres and formats, such as cinema, television films and television series, to the most recent ones, like video games and websites, these products are translated into different languages for audiences in different foreign markets. This journey from one language to another, i.e., from one culture to another, takes place thanks to audiovisual translation (AVT), the branch of translation studies focusing on the transfer of multimedia and multimodal texts into other languages and cultures (Pérez-González, 2014).

Audiovisual texts such as films or television series contain culture-specific elements that can be perceived by viewers through both its verbal and non-verbal components. From judicial and educational systems to gastronomy, the list of cultural aspects and fields is long. Conveying this type of meaning from a source to a target culture through translation can be a complex task. If the text to be translated is audiovisual, the process should, moreover, fulfil specific requirements related to the translation mode used. Among the different AVT modes, e.g., voice-over, subtitling, dubbing, free commentary, and narration, we have focused on dubbing and subtitling, the predominant methods in the languages and cultures in contact in our study.

Individuals accustomed to watching foreign audiovisual texts in cinemas, on television or the Internet are familiar with the concepts of dubbing and subtitling. However, they are not aware that these translation modes are characterised by technical aspects observed by professional translators that determine the kind of strategies to be applied when rendering the original dialogues in the foreign language. Regarding dubbing, Chaume (2016, p. 2) states that it “consists of replacing the original track where any audiovisual text’s source language dialogues are recorded with another track on which translated dialogues have been recorded in the target language”. For the translator, in terms of performance flexibility, a particularly important feature of dubbing is the fact that the original dialogue recording is removed and, as a result, viewers can hear only the translation. As for subtitling, Díaz-Cintas and Remael (2007, p. 8) define it as a linguistic practice through which a written text is presented, “generally on the lower part of the screen, that endeavours to recount the original dialogue of the speakers, as well as the discursive elements that appear in the image […] and the information that is contained on the soundtrack”, e.g., relevant songs and off-screen voices. Unlike dubbing, subtitles provide the translation at the same time as the original dialogue is heard in the source language and, consequently, subtitling is considered “an overt type of translation” (Gottlieb, 2004, p. 102). The target viewers have the chance to compare the original dialogues with the translation in the subtitles and, depending on their knowledge of the source language, they may not find the translation reliable if they detect differences in the content and length of utterances concerning the original text. For that reason, a certain degree of literalness in the translation is recommended (Díaz-Cintas, 2001).

The presence or absence of the original soundtrack in the translated or target text (TT) that characterises subtitling and dubbing very often constrains the translator’s decisions. Depending on whether the translation is to be produced for dubbing or subtitling, different techniques may be applied for the same linguistic element. Specifically, when dealing with culture-bound references, e.g., a joke, a pun, or a meaningful nickname, the difficulties of rendering meanings that do not exist in the target culture add to those produced by the technical requirements and conventions of the AVT modes.

While dubbing is the most widespread AVT mode in countries such as Italy, Spain, Austria, and Germany, subtitling is predominant in The Netherlands, Portugal, Greece, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Latin American countries. This preference regarding the method used highly influences the way viewers receive and perceive foreign audiovisual productions.

In this context, the study described in this article aims to identify and determine the translation techniques employed in the translation into English and Spanish of the contronomi—a special kind of nickname—used in the Italian series Gomorra. To achieve this objective, we have carried out an analysis of these linguistic cultural elements in the original or source text (ST), in the Neapolitan dialect, and the translated versions in Spanish and English. Specifically, comparisons have been made between the original version, the subtitled version in English, and the dubbed version in Spanish of the first season episodes. The initial hypothesis was that the English TT would resort to the preservation of the original nicknames since subtitling exposes the original dialogues to the viewers’ criticism, while the Spanish TT would present more varied and freer options because the soundtrack with the original voices disappears through dubbing. This analysis has helped us find out how these cultural linguistic elements have been re-expressed or represented in the two target languages and cultures in terms of translation tendency and to what extent they differ or coincide.

II. THE TRANSLATION OF NICKNAMES

According to Merriam-Webster (n.d.), a nickname is “a usually descriptive name given instead of or in addition to the one belonging to a person, place, or thing”. The Cambridge Dictionary (n.d.) defines it as “an informal name for someone or something, especially a name that you are called by your friends or family, usually based on your real name or your character”. The Oxford English Dictionary (n.d.) adds that this name is “usually familiar or humorous”. Putting these aspects together, a nickname is an informal name given to someone, usually related to their particular characteristics (either physical or character traits) and is sometimes created for humoristic purposes. As proper names do, nicknames function as ways to identify people.

As cultural elements are significant parts of speech, their use in audiovisual texts provides the dialogues (as fictional discourse) with the flavour of daily life in specific social and cultural contexts. Nicknames are not an exception and are especially related to more traditional societies and small communities. We should bear in mind that the dialogues of audiovisual texts are planned and written in advance to sound natural and spontaneous, giving rise to what Chaume (2004, p. 68) calls “prefabricated orality”. As Baños-Piñero and Chaume posit (2009, para. 3), “Depicting realism through dialogues seems to be one of the keys to creating a successful audiovisual programme”. This pretended naturalness of the made-up dialogues becomes one of the main challenges of AVT (Baños-Piñero & Chaume, 2009). In the case of dubbing, as Pettit (2009, p. 44) puts it, “the aim is to ensure that the dubbed dialogues feel as authentic as possible, yet the image betrays specific features of the source culture”. The results obtained in this study are also helpful to understand what each TT analysed takes as authentic, i.e., keeping the original nicknames or somehow adapting them.

II. 1. The translation of proper names as a starting point

Considering the scant number of studies on the translation of nicknames, it is useful to refer to the literature on translation techniques applied to proper names as a starting point. The translation of nicknames has usually been studied as part of the research on the translation of proper names, “as an anthroponymic subcategory” (Amenta, 2019, p. 233). More than thirty years ago, Bantas and Manea (1990) lamented the lack of research on the topic. Although more recently a still-small number of scholars have addressed the translation of nicknames directly as the focus of their studies (e.g., Yang, 2013; Peterson, 2015; Bai, 2016; Zhang, 2017; Amenta, 2019; Barotova, 2021) or tangentially as part of a wider textual analysis (e.g., García García, 2001; Muñoz Muñoz and Vella Ramírez, 2011; Epstein, 2012), most research is confined to the field of literature.

Beyond the well-known debate about the translatability of proper names, discussed by Mayoral (2000) and Cuéllar Lázaro (2014), we will look at the basic premises generally applied to the translation of proper names. In general, proper names of distinguished personalities are usually adapted (e.g., names of popes, kings, and queens), but preserving the proper name in its original language is common practice when dealing with real people’s names (Moya, 1993). When fictional characters’ names are involved, there are no fixed rules in that regard. The selection of one of the two options depends on whether the name has a special meaning or lacks recognisable descriptive elements. As Nord (2003) puts it, the names in the first group could be literally translated in order to keep their descriptive meaning and those in the second group would be transcribed as they are used in the ST. According to this scholar, beyond these criteria, one more aspect is still to be considered when approaching the translation of personal names, i.e., their function, which can be informative or a cultural marker. When the information contained in a descriptive name is explicit, it can be translated. However, if it is implicit, or if the marker function is to be prioritised, “this aspect will be lost in the translation, unless the translator decides to compensate for the loss by providing the information in the context” (2003:85). Proper names with explicit descriptive characteristics lead us necessarily to the notion of nicknames. Although proper names and nicknames are conceptually different, their translation can be addressed similarly, hence the pertinence of the research on the translation of proper names to this topic.

II.2. Applicable translation techniques

Scholars who have paid special attention to the translation of proper names have produced taxonomies of translation techniques that can be applied to these elements (e.g., Hermans, 1988; Newmark, 1988; Hervey and Higgins, 1992; Ballard, 1993; Moya, 1993, 2000; Mayoral, 2000; Davies, 2003; Van Coillie, 2006; Salmon, 2006). Specifically, Davies (2003) considers nicknames as a subgroup of proper names in her classification of techniques intended for the translation of culture-specific items.

Despite terminological and conceptual disagreement among translation scholars concerning translation techniques (Molina & Hurtado Albir, 2002), which can be seen in the classifications of the previous researchers, their most common translation operations can be grouped as follows:

- Keeping the ST name unchanged in the TT. Through this technique, the TT stays closer to the ST by preserving the original culture and may seem more realistic and more easily located. However, if the proper name is semantically loaded, the target language receiver will most probably miss its meaning. An added disadvantage is that, when the TT is to be read, the receivers could find it difficult to read the proper names in the source language when their phonic and graphic rules are too distant from those of the target language. The names given by scholars to this technique are varied (e.g., exotism, copying, transfer, transference, preservation, non-translation, reproduction).

- Adapting the ST name to the phonic or graphic rules of the target language. This technique aims at fulfilling the expectations of the receivers of the TT (called transliteration, transcription, naturalisation, localisation, and adaptation).

- Altering the ST name in the target language. Through this technique, the name is partially modified (called transformation and replacement).

- Translating the ST name into the target language literally. This applies when dealing with meaningful or semantically-loaded names and nicknames (called translation and semantic recreation).

- Creating a proper name that is different from the one in the ST. As Davies (2003: 88) posits, this technique is used when the original proper name “seems too alien or odd in the target culture” and when “it is desired to make the target version more semantically transparent, in order to convey some descriptive meaning” (called creation and replacement).

- Replacing the ST name with a target language name with the same cultural connotation (called cultural transplantation, substitution, and replacement).

For the sake of clarity, in their application to our study, we will refer to these techniques as (1) preservation, (2) naturalisation, (3) transformation, (4) translation, (5) creation, and (6) cultural transplantation. According to the linguistic operations involved and their effects on the TT, they are along a continuum from foreignization to domestication (as coined by Venuti, (1995)), i.e., from the transference to the adaptation of foreign elements to the target culture. While foreignizing techniques reproduce the cultural idiosyncrasy of the ST, domesticating techniques make the TT closer to the context of the target culture. In the middle of these opposite points, neutralisation pursues the removal of cultural marks. The application of these strategies depends on the translation norms of the target language and culture, which together with local policies and ideologies can influence the translator’s performance (Spiteri Miggiani, 2019).

While preservation is the most foreignizing technique, creation and cultural transplantation are the most domesticating ones, since they aim at replacing the original name with a name that is common or, at least, more acceptable in the target culture. Naturalisation and transformation are on the way towards domestication but keep the essence of the name of the ST, because, through these techniques, the names are only adapted phonetically or slightly altered and, thus, the audience can still recognise them as foreign. Although translation is near the domesticating end since its use results in an item that is completely inserted in the recipient’s linguistic universe, it is a neutralising technique.

The application of these techniques in the translation of nicknames can result in two main effects, i.e., either keeping the cultural component (as a cultural marker), thus, probably hiding the semantic load, or showing the way the bearer of the nickname is seen or considered in the ST and, consequently, missing the cultural load. In this study, we will observe which of these two options defines the translation tendency for the nicknames found in the series Gomorra in English and Spanish.

II. DATA AND METHODOLOGY

The Italian TV series Gomorra was broadcast for the first time in Italy, in May 2014, on the channel Sky Atlantic of the Sky satellite platform. In the UK, it was launched at the beginning of August 2014 on Sky Atlantic and then in the USA at the end of the same month on the Sundance TV channel. In Spain, it was shown on television in September of the same year on La Sexta.

The series is based on the book Gomorra - Viaggio nell’impero economico e nel sogno di dominio della camorra, a bestseller by Roberto Saviano (2006), and its story is set in Naples in the 2010s. It deals with the Savastano mafia family, the main drug-dealing group of the Neapolitan neighbourhood called Secondigliano, and their enemy, Salvatore Conte. Pietro Savastano, the patriarch, has entrusted his right-hand man, Ciro di Marzio, with training his son, Gennaro Savastano, to take on the role of the next capo, that is, the new boss of the neighbourhood and the family.

Saviano (2021) said to the Italian newspaper Corriere della sera that the real underlying message of the novel is not about a conflict between organised crime groups but about the conflict between groups of people who want to control a territory to use it to their advantage and rule it through intimidation.

In terms of linguistic features, the TV series Gomorra is a peculiar case because the original script is written in Neapolitan dialect and the episodes are broadcast with an option to see them with standard Italian subtitles. In this audiovisual product, the dialect spoken by the characters is extremely important because it shows their roots and their belonging to a specific geographical context and a specific moment. The dialect plays the role of highlighting the relationships among linguistic variety, culture, society, and territory. The typological and structural differences between standard Italian and Neapolitan make Neapolitan to be considered a code by itself (Marano, 2010). UNESCO recognises Neapolitan as a language which, compared to Italian, has been influenced not only by Latin but also by other languages like Greek, Spanish, French, and Arabic.

In this social and linguistic context, contronomi (plural form of contronome) play an important role in putting not only a name but also a face to the power groups represented by the mafia clans in this series. According to Giuntoli (2018), they are a kind of surname given to the most important members of the Camorra group in Naples. The expression contronome is a Neapolitan dialectal word (soprannome in standard Italian) whose meaning depends sometimes on diatopic varieties within the same geographical region. He adds that if we asked Neapolitans what the word contronome means, we would surely receive different answers. Some will even affirm that it is a synonym of ‘surname’, but Bianchi (2013) states that, in the context of the Camorra, these culture-specific linguistic elements are usually equivalent to nicknames.

As Bianchi (2013) puts it, people started using contronomi in their private lives or in small groups in order to distinguish people informally and humorously according to individual characteristics. This type of naming shows more personality than the first name or the surname and, thus, makes it easier to identify people, especially in small communities and delimited social contexts. Thus, these special nicknames meet not only a practical need but also a need to express oneself by being amusing or, sometimes, irreverent. They may refer, directly or indirectly, to people’s physical or character traits, to their birthplace, their language, or the way they express themselves. This way of addressing or referring to others is confined to the spoken language and its use in the written language is limited to private communication such as letters and emails. Since these expressions belong to the linguistic variety of the community using them, they usually present morphological, lexical, semantic, graphic, and phonetic traits of the dialect of the area where they are used.

Although nowadays the contronomi system, especially in the biggest cities, is seen as an old sociolinguistic structure on the verge of disappearing, unless it is used by young people as a way of social cohesion and expression of friendliness (Bianchi, 2013), the relevance of contronomi in the context of the Camorra makes their study worthy as a linguistic phenomenon. As explained by Saviano (2006), in the communication among members of the mafia group, contronomi present two relevant functions: first, they hide the criminal’s real name to keep their identity unknown by civil society and judicial structures; and second, having a contronome implies their belonging to that group (the Camorra, in this case) and shows the shared inner knowledge they have of people and situations within the group. In the Camorra clan, sometimes the contronome is hereditary from father to son and can mark that they are members of the same family.

Bianchi (2013) states that, in recent years, the attribution of contronomi in the Camorra has evolved together with society and, thus, to the list of traditional contronomi of the Neapolitan dialect, other nicknames have been added that derive from the names of celebrities and cartoon and comic book heroes, or the favourite food of the camorrista (member of a Camorra clan). This new trend in the creation of contronomi contributes to the use of a combination of foreign words, especially anglicisms, and dialectical expressions of the Camorra. We will observe these features in the main characters’ contronomi analysed for this study in the first season of the series Gomorra.

To conduct this study, we have used the DVD versions of the series distributed in Spain and the UK. Specifically, we have analysed the dubbed version in Spanish and the subtitled version in English of the twelve episodes of the first season (out of five). Each episode is approximately 50 minutes long. The reason for comparing Gomorra in two different translation modes is that these were the AVT modes through which the corresponding target audiences had first access to the series in these countries.

The taxonomy of techniques we have used to describe the way these contronomi have been rendered in the TT is the following (their corresponding abbreviations for subsequent use in Table 1 are shown in brackets):

- Preservation (Pres): Transferred without alterations (e.g., Malammore – Malammore)

- Naturalisation (Nat): Phonetically adapted (e.g., Trak – Track)

- Transformation (Tran): Partially altered (e.g., Africano – Africa)

- Translation (Trans): Literally translated (e.g., Zingaro – Gipsy)

- Free translation (FTrans): Non-literally translated but related to the meaning of the original naming (e.g., Centocapelli – Hairball)

- Omission (Om): Omitted

- Creation (Cre): Newly created

- Cultural transplantation (CT): Replaced with a nickname of the target culture

For the purposes of this study, we have included the free translation technique in order to be able to explain those cases where a literal translation attempting to reproduce the exact meaning of the original utterance would have resulted in a non-idiomatic expression. Also, since the omission of linguistic elements is a common practice in the context of AVT due to the constraints imposed by the AVT modes, e.g., a limited number of characters per line and second, we have added omission. The effects produced by both techniques tend to be neutralising, hence the position they have in the list of techniques reproducing the continuum from preservation to cultural transplantation.

The fifteen contronomi of members of the two main Camorra clans portrayed in the series that we found and analysed are shown and commented on in the next pages. A short explanation of the meaning of the Italian expression is given to help discern the motivation for the use of each translation technique in the two target languages.

III. ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

The analysis of data provides the list of contronomi which are given in Table 1, below. The first column includes the contronomi found. The second and third columns present the corresponding expressions in the dubbed TT in Spanish and the subtitled TT in English, respectively. Finally, the techniques applied in both languages are specified in the fourth column.

Table 1. List of contronomi in the ST and TT, and translation techniques used

|

ST (Neapolitan) |

TTS (Spanish dubbing) |

TTE (English subtitling) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Malammore |

Malammore |

Malammore |

Pres/Pres |

|

Zecchinetta |

Zecchinetta |

Zecchinetta |

Pres/Pres |

|

Pop |

Pop |

Pop |

Pres/Pres |

|

Tonino Spiderman |

Tonino Spiderman |

Tonino Spiderman |

Pres/Pres |

|

Immortale |

Inmortal |

Immortal |

Trans/Trans |

|

Zingaro |

Gitano |

Gypsy |

Trans/Trans |

|

Leccalecca |

Piruleta |

Lollipop |

Trans/Trans |

|

Lisca |

Lisca |

Fishbone |

Pres/Trans |

|

Baroncino |

Baroncino |

Little Baron |

Pres/Trans |

|

Bolletta |

Bolletta |

Bookie |

Pres/FTrans |

|

Centocapelli |

Centocapelli |

Hairball |

Pres/FTrans |

|

Capa ‘e bomba |

Capa ‘e bomba |

Bomber |

Pres/FTrans |

|

Africano |

Africano |

Africa |

Pres/Tran |

|

Bellillo |

Bellillo |

- |

Pres/ Om |

|

Trak |

Trak |

Track |

Pres/Nat |

As we can observe, most nicknames have been preserved in the Spanish version, while the English version has usually resorted to other techniques, including transformation, translation, free translation, and naturalisation. It is important to note not only that naturalisation has not been used in the dubbed Spanish version but also that the dubbing actors imitate the original pronunciation of the contronomi in the TT.

We will first look at those contronomi that have been preserved in both the Spanish and the English versions. Malammore, spelt “malamore” in standard Italian, which means “bad love” or “lovesickness”, is the contronome of a mafia member who was born when his mother was sixteen and who never met his father. He considers himself to be the son of mistaken love. The use of the preservation technique in both languages may be due to the recognition by Spanish and English speakers of this expression made up of the Italian words “mal” and “amore”. The prefix “mal-” is used in English and Spanish to form many words. The word “amore” evokes the cultural background exported by Italians, for example, in world-famous love songs. By this technique, the target versions transmit the Italian (or even Neapolitan) flavour of the series to the target viewers. Regarding Zecchinetta, the bearer of this contronome runs the drug business in an area of Naples. The Zecchinetta (Lansquenet, in English) is the name of a gambling card game introduced in Italy in the fifteenth century by German mercenary soldiers called Landsknecht, meaning “servant of the country”. We can see a link between his mafia duties and his nickname. Preserving this contronome has stripped both target versions of the meaning associated with the character’s personality or way of life. Thus, the expression in the TTs acts as a proper name since the word “zecchinetta” is unlikely to be identified by the target viewers as the Italian name of a card game.

The other contronomi preserved in both languages are English expressions. Pop is one of the latest members of the clan led by Gennaro and one of his closest friends. His contronome is an English expression that can be associated with the character in different ways. Apart from being the abbreviation of “popular culture” or “pop culture” and the lifestyle that comes along with it (group identity and belonging to a specific area), it can also refer to the sound of an explosion or a gunshot (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.) or even be related to drug dealing (Urban Dictionary, n.d.). As for Tonino Spiderman, the reference to the well-known fictional hero, according to Bianchi (personal communication, March 2, 2020), responds to the fact that the youngest mafia members usually imitate characters of the cinematic universe to gain popularity in their group.

Several contronomi were literally translated into both languages. Specifically, according to the story, the character called Immortale was the only person found alive after the block of flats where he was living with his family had been destroyed by an earthquake that killed nearly 2,500 people. The Italian word is so similar in form and meaning to the English and Spanish ones (“immortal” and “inmortal”, respectively), that a literal translation produces the most natural effect. In the case of Zingaro, literally translated as “Gypsy” in English and “Gitano” in Spanish, its attribution to this character may be due to his lifestyle or physical traits. Unlike in most cases, the Spanish version also draws upon translation. As for Leccalecca, the bearer of this contronome is a loan shark. It means “drug” in the clan’s slang, which is again associated with the drug-dealing business in which most of the characters are involved. It has been literally translated as “Lollipop” in English and “Piruleta” in Spanish.

The next two contronomi have been translated into English and preserved in Spanish. The first one, Lisca, is a word used in the Neapolitan dialect and standard Italian, meaning “bone” or “fishbone”, which may point to a very thin person. While literally translated into English as “Fishbone”, the preservation technique has been used in the Spanish version although the original meaning could be rendered through a literal translation. This is worth highlighting since the Spanish TT is the dubbed version; that is, the original track cannot be heard by the target viewers and, thus, the text can be easily manipulated for the sake of making explicit the connection between the character and his name. However, for the English TT, displayed using subtitles, a translation has been used. The second one is Baroncino, one of the eldest members of the Savastano clan. It means “little baron”, which in turn refers to “son of a baron”, suggesting he is the son of an important mafia boss. While the literal translation in the English version allows its viewers to associate his name with his relevance to the Savastano family, the preservation in the Spanish version hides this link.

The next three contronomi have been freely translated in the English version and preserved in the Spanish one. Bolletta, which literally means “bill”, runs the drug-dealing business in the centre of Naples. His role as the manager of the drug-dealing money and his contronome are linked. While it is preserved in the Spanish version, the English version opts for “bookie”, an informal word for “bookmaker”. According to Merriam-Webster (n.d.), a “bookie” is “a person who determines gambling odds and receives and pays off bets”. Due to the homonymy in “bill” as “a written statement of money that you owe for goods or services” (Collins English Dictionary, n.d.) and “Bill”, the hypocorism of William, a literal translation could be perceived as an English personal name by the target viewers. Regarding Centocapelli, which literally means “a hundred hairs” and may refer either to hairy or bald people, while it has been preserved in Spanish, the free translation “hairball” was used in English, which has a similar meaning. The last free translation technique applied in the English version is that produced for Capa ‘e bomba, literally meaning “bomb headed”, which hints at a person with a big head or who is not very bright. While preserved in the Spanish version, it has been replaced with “Bomber” (as someone who explodes or makes bombs) in the English subtitles. The translator may have been misled by the word “bomba” (“bomb” in English) and thought that the contronome had something to do with weapons and bombs, deciding to translate it as “bomber” to give the character a nickname related to violence and weapons in the criminal context of the series.

For the last three contronomi, different techniques have been applied in the English version while in the Spanish dubbing, again, preservation has been chosen. The contronome Africano (meaning “African”) could refer to the character’s facial features and skin colour. While in the Spanish dubbed version the use of the preservation technique results in an identical word in this language (spelt in the same way), in the English version it was transformed into “Africa”. Instead of the demonym “African”, the toponym has been used.

The character known as Bellillo appears only once in the first season (episode 7). The Italian word is made up of “bello”, meaning “handsome”, which alludes to the physical traits of the character, and the diminutive suffix “-illo” since he is one of the youngest members of the clan. The Spanish version preserves the contronome, thus hiding the link between the character and his contronome from Spanish viewers. As pointed out before, in the Spanish version all the nicknames preserved are pronounced in Italian by the Spanish dubbing actors. In the English version, the contronome is omitted, probably for the sake of complying with the subtitling norms, e.g., a limited number of characters per line and second. The Neapolitan utterance in the ST “Oh, Bellillo, vamme a piglia’ la macchina, Vengo subit’” is translated into Spanish through dubbing as “Bellillo, vete a por el coche. ¡Nos vamos!” and into English through subtitling as “Go get me my car, / I’ll be right there”, where “\” represents the subtitle division into two lines. The length of these utterances in the dialogue track of the ST suggests the need to reduce the number of characters in the TT. When this happens, it is common practice to omit vocatives.

Finally, the contronome Trak recalls the noise of firework explosions, common in Naples, where excessive use of fireworks is made during bank holidays such as New Year’s Eve. The tric trac (regional term, according to Dizionàrio Treccani (n.d.)) is a kind of firework that produces a repetitive noise when exploding. By adapting the word phonetically (adding a “c” before the “k”), the English translator used a naturalisation.

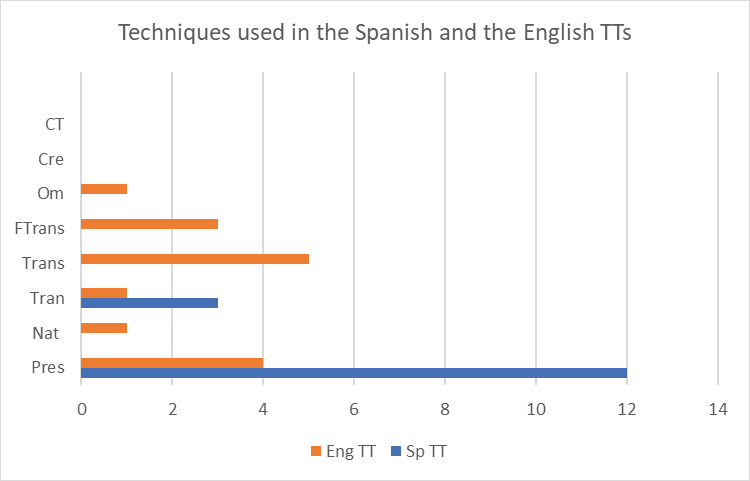

Although the number of contronomi found in these episodes of the series is small, the translation tendency in each target language regarding the treatment given to these culture-bound linguistic elements of the ST, originally written in Neapolitan, is evident. As shown in Table 1, above, out of the fifteen nicknames observed, twelve have been preserved—i.e., transferred with no changes—in the dubbed version in Spanish and only three of them have been translated. No other techniques have occurred in this TT. Consequently, preservation has proved predominant in this language. As for the subtitled version in English, the techniques applied have been varied: four cases of preservation, one of naturalisation, one of transformation, five of translation, three of free translation, and one of omission. No instances of creation and cultural transplantation have been found. Figure 1, below, is illustrative of the differences between the Spanish and the English versions.

It is relevant to note that, despite preservation cases, most techniques used in the English TT are oriented towards neutralisation since the preserved contronomi were already in English in the Neapolitan version of the series (Pop and Spiderman). Only two preservations were truly foreignizing: Malammore and Zecchinetta, of which the first can be understood by English-speaking viewers, as explained before, and the second is difficult to translate, although the creation technique could have been resorted to. Both the only transformation and the three free translations have resulted in English expressions. The tendency in the English version, thus, has been to bring the contronomi closer to the viewers of the target culture by rendering their meaning.

Quite the opposite, the tendency in Spanish is foreignization. Since Spanish viewers cannot understand most of the contronomi in the Neapolitan dialect, they may perceive them as the characters’ proper names or surnames, e.g., Zechinetta, Centocapelli, Bolletta. Consequently, they may only recognise the translated ones (Inmortal, Piruleta, and Gitano) as real nicknames and, thus, construct the link between those characters and what they are called. Bearing in mind that these contronomi not only portray physical or personality traits of their bearers (Lisca, Africano, Centocapelli, Bellillo, Zingaro, and Capa ‘e bomba) but also relevant events in their lives (Malammore and Immortale) and the job they do within the corresponding mafia group (Zecchinetta and Bolletta), the dubbed version in Spanish tends to widen the distance between its viewers and the personal features and stories of the characters.

These results are far from what we expected. Coinciding with Valdeón’s view of subtitling as “a more honest mode than dubbing” (2022, p. 371), although more intrusive, we expected the English subtitled version to be nearer foreignization and the Spanish dubbed version to resort to domesticating techniques.

Both directions on the continuum of translation techniques presented at the beginning of Section III have advantages and disadvantages. When the balance is tilted towards foreignization, the Neapolitan or Italian flavour of the ST is transmitted in the TT, but keeping this element in the TT is detrimental to the transparency of the nickname. However, domesticating and neutralising techniques “may interfere with the function of culture marker” (Nord, 2003, p. 185).

IV. CONCLUSIONS

This study has shown how the contronomi, as special kinds of nicknames of the members of the mafia groups portrayed in Gomorra, are exposed to the Spanish and English-speaking viewers of the Italian series, set in Naples and originally written in Neapolitan. This has been achieved in terms of translation techniques, for which we have designed a classification based on existing models that cover the samples found in the audiovisual texts analysed.

Although the analysis of the techniques used in two different AVT modes could seem to produce results that are not comparable, from the point of view of this study these results respond to our main research question. We wanted to know in what way these intrinsically Neapolitan linguistic elements (contronomi) are presented to their respective target viewers in the different cultures through translation techniques. The answer to this question has also encompassed whether the link between the characters and their contronomi can be identified by these audiences or whether these linguistic culture-bound elements are perceived as mere proper names.

In principle, AVT modes such as subtitling and dubbing pose different difficulties and challenges. This requires, therefore, different solutions or techniques to cater for specific micro-textual elements (e.g., one of the contronomi analysed was omitted in the English subtitling surely due to the specific technical norms of subtitling). At the same time, when dealing with culture-bound elements, decisions need to be made regarding the method to be used depending on a variety of aspects, e.g., the text type, the genre, the target audience, the translation norms in the social and cultural context where the translated audiovisual text is to be watched, and the translator’s preferences. This concurrence of factors usually determines the final product.

In this study, regarding the translation of the elements analysed, contrary to our initial expectations, we have found that the neutralising behaviour observed in the English TT is in marked contrast to the foreignizing attitude perceived in the Spanish TT. While the English translation presents a variety of techniques, the Spanish version has been limited to the use of two of them, preservation and translation, of which the former, i.e., the most foreignizing one, is noticeably predominant. However, choosing the method implies the need to choose not only which aspect to maintain, either the Neapolitan flavour of the contronomi or its meaning, but also which one to sacrifice. As we have seen, the translation of nicknames “is one of those matters which go beyond the dictionary” (Bantas and Manea, 1990, p. 183).

V. REFERENCES

Amenta, A. (2019). Translating Nicknames: The Case of Lubiewo by Michal Witkowski. Kwartalnik Neofilologiczny, 64(2), 230-239. https://doi.org/10.24425/kn.2019.128396

Bai, Y. (2016). A Cultural Examination of Shapiro’s Translation of the Marsh Heroes’ Nicknames. Advances in Literary Study, 4, 33-36. https://doi.org/10.4236/als.2016.43006

Ballard, M. (1993). Le Nom Propre en Traduction. Babel 39(4), 194-213. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.39.4.02bal

Baños-Piñero, R., & Chaume, F. (2009). Prefabricated Orality: A Challenge in Audiovisual Translation. Intralinea, 6. https://www.intralinea.org/specials/article/1714

Bantas, A., & Manea, C. (1990). Proper names and nicknames: Challenges for translators and lexicographers. Revue roumaine de linguistique, 35(3), 183-196.

Barotova, M. (2021). Some Features of Translating Original Literary Text. JournalNX, 7(3), 369-373.

Bartoll, E. (2008). Paramètres per a una taxonomia de la subtitulació. Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Versión electrónica: http://hdl.handle.net/10803/7572

Bianchi, P. (2013). I soprannomi dei camorristi. Biblioteca digitale sulla camorra e cultura della legalità. Università di Napoli Federico II. https://www.bibliocamorra.altervista.org/pdf/i_soprannomi_dei_camorristi_Patricia_Bianchi.pdf

Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.). Nickname. In Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved January 16, 2023, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/nickname

Chaume, F. (2004). Cine y Traducción. Cátedra.

Chaume, F. (2016). Dubbing a TV drama series. The case of The West Wing. Intralinea, 18, 1-18.

Collins English Dictionary. (n.d.). Bill. In Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/bill

Cuéllar Lázaro, C. (2014). Los nombres propios y su tratamiento en traducción. Meta, 59(2), 360-379. https://doi.org/10.7202/1027480ar

Davies, E. (2003). A Goblin or a Dirty Nose? The Treatment of Culture-Specific References in Translation of the Harry Potter Books. The Translator, 9(1), 65-100.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2003.10799146

Díaz-Cintas, J. (2001). La traducción audiovisual. El subtitulado. Almar.

Díaz-Cintas, J., & Remael, A. (2007). Audiovisual Translation: Subtitling. Routledge.

Dizionàrio Treccani. (n.d.). Tric trac. In Dizionàrio Treccani. Retrieved January 13, 2023, from https://www.treccani.it/vocabolario/tric-trac_(Sinonimi-e-Contrari)

Epstein, B. J. (2012). Translating Expressive Language in Children’s Literature: Problems and Solutions. Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-0353-0271-4

García García, O. (2001). La onomástica en la taducción al alemán de Manolito Gafotas. Anuario de Estudios Filológicos, 24, 153-167.

Giuntoli, G. (2018). Sul concetto di “contronome” in Gomorra di Roberto Saviano. Onomàstica. Anuari de la Societat d’Onomàstica, 4, 49-62,

https://raco.cat/index.php/Onomastica/article/view/369746

Gottlieb, H. (2004). Language-political implications of subtitling. In P. Orero (Ed.), Topics in Audiovisual Translation (pp. 83-100). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.56.11got

Hermans, T. (1988). On translating proper names, with reference to De Witte and Max Havelaar. In M. J. Wintle (Ed.), Modern Dutch Studies. Essays in Honour of Professor Peter King on the Occasion of his Retirement (pp. 1-24). The Athlone Press.

Hervey, S., & Higgins, I. (1992). Thinking Translation. A Course in Translation Method – French to English. Routledge.

Marano, L. (2010). Aspetti sintattici dell’italiano parlato a Napoli. Un’analisi diagenerazionale [Doctoral dissertation, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico I]. Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico I, http://www.fedoa.unina.it/8035/

Mayoral, R. (2000). La traducción audiovisual y los nombres propios. In L. Lorenzo García, & A. M. Pereira Rodríguez (Eds.), Traducción subordinada (I) (inglés-español/galego). El doblaje (pp. 103-114). Universidad de Vigo.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Nickname. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved March 1, 2023, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/nickname

Molina, L., & Hurtado Albir, A. (2002). Translation Techniques Revisited: A Dynamic and Functionalist Approach. Meta, 47(4), 498-512. https://doi.org/10.7202/008033ar

Moya, V. (1993). Nombres propios: su traducción. Revista de Filología de la Universidad de La Laguna, 12, 233-248.

Moya, V. (2000). La traducción de los nombres propios. Cátedra.

Muñoz Muñoz, J. M., & Vella Ramírez, M. (2011). Intención comunicativa y nombres propios en la traducción española de Porterhouse Blue. Trans. Revista de Traductología, 15, 155-170. https://doi.org/10.24310/TRANS.2011.v0i15.3201

Newmark, P. (1988). A Textbook of Translation. Prentice Hall.

Nord, C. (2003). Proper Names in Translations for Children. Alice in Wonderland as a Case in Point. Meta, 48(1-2), 182-196. https://doi.org/10.7202/006966ar

Oxford English Dictionary. (n.d.). Nickname. In Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved March 1, 2023, from https://www.oed.com/search/dictionary/?scope=Entries&q=nickname

Pérez-González, L. (2014). Audiovisual Translation Theories, Methods and Issues. Routledge.

Peterson, P. R. (2015). Old Norse Nicknames. (Publication No. 3706936) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota]. ProQuest LLC.

Pettit, Z. (2009). Connecting Cultures: Cultural Transfer in Subtitling and Dubbing. In J. Díaz-Cintas (Ed.), New Trends in Audiovisual Translation (44-57). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847691552-005

Salmon, L. (2006). La traduzione dei nomi propri nei testi fizionali. Teorie e strategie in ottica multidisciplinare. Il Nome nel testo. Rivista Internazionale di Onomastica letteraria, 8, 77-91.

Saviano, R. (2006) Gomorra - Viaggio nell’impero economico e nel sogno di dominio della camorra. Mondadori.

Saviano, R. (2021, August 20). Chi sono i Savastano, famiglia di potere e crimine, ma così simile alle altre. Corriere della Sera.

Spiteri Miggiani, G. (2019). Dialogue writing for dubbing. An insider’s perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04966-9

Treccani Dizionario (n.d.). Tric trac. In Trecanni Dizionario. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://www.treccani.it/vocabolario/ricerca/tric-trac/

Urban Dictionary. (n.d.). Pop. In Urban Dictionary. Retrieved October 3, 2022, from https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=a+pop

Valdeón, R. A. (2022). Latest trends in audiovisual translation. Perspectives, 30(3), 369-381. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2022.2069226

Van Coillie, J. (2006). Character Names in Translation. A Functional Approach. In J. Van Coillie, & W. P. Verschueren (Eds.), Children’s Literature in Translation: Challenges and Strategies (pp. 123-139). St. Jerome.

Venuti, L. (1995). The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. Routledge.

Yang, L. (2013). Cultural Factors in Literary Translation: Foreignization and Domestication---On the Translating of Main Characters’ Nicknames in Two Translations of Shui Hu Chuan. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(13).

Zhang, X. (2017). On Translation of Nicknames in Chinese Classic Novel Outlaws of the Marsh. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 8(4), 122-125. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.8n.4p.122

Received: 03 May 2023

Accepted: 27 September 2023