Stance matrices licensing that-clauses and interpersonal meaning in nineteenth-century women’s instructive writing in English

Discourse, Communication and Society Research Group

Departamento de Filología Moderna, Traducción e Interpretación,

Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain

ABSTRACT

This paper examines stance matrices licensing that-clauses in a corpus of instructional texts authored by women during the nineteenth century, gathered under the label COWITE19. These matrices can reveal various aspects of the authors' assessment, involvement and understanding of the information they present. In other words, their use discloses the authors' evaluation of their text while conveying a wide range of interpersonal meanings without disregarding their organising potential as textual markers. The types of matrices explored in this article precede the that-clauses and generally contain information denoting authorial perspective and involvement. The data used to demonstrate their forms and functions derive from analysing all cases found in the Corpus of Women's Instructive Texts in English (1550–1900) (COWITE); for the current study, only the nineteenth-century sub-corpus, henceforth COWITE19, has been considered. This corpus exclusively comprises instructional texts penned by women during the nineteenth century. The findings reveal that although the corpus primarily encompasses recipes from a diverse range of registers, the authoritative voice of women is distinctly evident in the matrices analysed, conveying a series of interpersonal meanings that unequivocally highlight the experience of women writers and their adept command of the content and techniques being discussed.

Keywords:women's writing; that-clauses; interpersonal meanings; involvement; modality; evidentiality; nineteenth century.

I. INTRODUCTION

The use of matrices in writing reveals much about a writer's thought process and approach to reality, while it may also show how writers engage with their own texts, as these constructions have strong connections to evaluation. Scholars such as Mauranen and Bondi (2003), Stotesbury (2003), Jalilifar, Hayati and Don (2018) and Alonso-Almeida and Álvarez-Gil (2021a) have focused on how this concept applies to the analysis of academic and technical discourse. Stance matrices licensing that-clauses embody much of the evaluative content that may modulate or complete the propositional content given in the subordinating clause, as demonstrated in Hyland and Tse (2005a; 2005b), Hyland and Jiang (2018b), Kim and Crosthwaite (2019) and more recently in Alonso-Almeida and Álvarez-Gil (2021a), which focused on earlier English texts. The use of these devices reveals the authors' estimation of their own text while also allowing them to convey a wide range of interpersonal meanings without disregarding their organising potential as textual markers. As I will demonstrate, the interpersonal dimension of these features may report on authorial involvement and epistemic and affective modulation of propositional information in the sense of Langacker (2009) to signal such meanings as probability, necessity, obligation and mode of knowing, among many others. In this context, the contribution of these devices to characterise the authors' perspective by focusing on the degrees of affect and the use of these forms may entail.

The type of matrices I will focus on in this text are those licensing that-clauses (Charles, 2007; Hyland & Tse, 2005a) and which generally convey the information designating the authors' stance and involvement. The data used to illustrate their forms and functions is derived from my analysis of all instances found in the Corpus of Women's Instructive Texts in English (1550–1900) (COWITE); this time, my analysis of data has only considered the nineteenth-century subcorpus, hereafter COWITE19. This corpus is entirely composed of women's instructive writings, primarily recipes. The following are my research questions: (a) what forms of stance matrices licensing that-clauses appear in COWITE19, (b) which of these matrices are more common in these texts, (c) what meanings do these forms entail and (d) what are the pragmatic implications.

This article is organised as follows. Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of prior literature pertaining to the subject matter under investigation, which has been instrumental in identifying and interpreting the samples discovered in COWITE19. Subsequently, Section 3 delineates the corpus and methodology employed for corpus interrogation and data analysis. Section 4 presents the results, accompanied by a discussion of examples that illustrate the diverse matrix forms identified within the corpus. Finally, the concluding remarks of this study are presented in the last section.

II. MATRICES LICENSING THAT-CLAUSES AS STANCE DEVICES

The evaluative characteristics of matrices licensing that-clauses are embodied by stance language, which denotes writers' 'personal feelings, attitudes, value judgements or assessments' (Biber et al., 1999, p. 966). The interpersonal significance of stance-taking structures is evident in Clift (2006) and can encompass various concepts, such as evaluation (Martin, 2000; Mauranen & Bondi, 2003), evidentiary justification (Alonso-Almeida & Carrió-Pastor, 2019; Estellés & Albelda-Marco, 2018; Chafe, 1986; Marín-Arrese, 2011), affectivity and social relations (Abdollahzadeh, 2011; Hyland, 2005a; Wetherell, 2013), authority (Fox, 2008; Kendall, 2004) and mitigation (Alonso-Almeida, 2015; Caffi, 2007; Hyland, 1998; Hyland, 2005b), among others.

As highlighted by Halliday and Matthiessen (2014, p. 30) and Johnstone (2009, pp. 30-31), stance devices not only evaluate how authors relate to their texts but also indicate how they may wish to build rapport with their audience, thereby contributing to the creation of a shared semiotic space in which the information is both relevant and likely to be accepted. This might explain why deontic expressions in instructive writing are not perceived as patronising or abusive but as empathetically authoritative, as these expressions aim to help readers achieve their goals.

The interpersonal aspect of evaluative language has also been explored in the works of Crismore and Farnsworth (1989), Vande Kopple (2002), Hyland (2005b), Abdollahzadeh (2011), Rozumko (2019), Carrió-Pastor (2012, 2014, 2016) and Álvarez-Gil (2022). With respect to the structures examined in this study, Hyland and Tse (2005a, p. 40) suggest that they are 'perhaps one of the least noticed of these interpersonal' devices. However, their near-fixed position within the sentence's focus location appears to signify their importance in both text modelling and the pragmatic and rhetorical functions they may serve. In addition to their modulating ability to convey various degrees of probability that an event may occur or expectations and concerns regarding these occurrences, they can also be used to demonstrate how knowledge has been constructed or acquired. These applications affect how readers receive and accept information, thus revealing their potential function as persuasive technical and professional communication strategies.

Stance matrices licensing that-clauses can take various forms, including the presence of copulas or lexical verbs, as for example, some people are of the opinion..., scholars believe..., we should consider..., it is often said... From a semantic perspective, matrices are regarded as either the source of evaluation or simply the evaluation itself, while the information provided in the accompanying that-clause represents the evaluated entity, as proposed by Hyland and Tse (2005a, p. 40). The following example in (1) summarises and illustrates this concept. The evaluation contains a volitive argument concerning the event described in the evaluative entity – that is, the fact that the biofunctional account is potentially adequate to provide more content specificity than previously believed.

- [evaluation & source of evaluation ] I will show [evaluated entity ] that the biofunctional account can give us more content specificity than Fodor supposes. (Hyland & Jiang 2018b, p. 140)

- …there is evidence that traders may reduce their costs from trading by splitting orders so as to dampen the pressure on inventory holding (Hyland & Tse, 2005a, p. 42).

- …it is possible that mainstream teachers overcompensate and are especially lenient with NNSS (Hyland & Tse 2005b, p. 125).

- One finds that good eating is not a forgotten art, and that Italian cookery has its own very distinctive features (Campbell, 1893); verb.

- You are to observe, that force-meat balls are a great addition to all made dishes (Holland, 1825); verb.

- Never leave out your clothes-line over night; and see that your clothes-pins are all gathered into a basket (Mrs Child, 1841); verb.

- It should, however, be borne in mind that the ham must not remain in the saucepan all night (Beeton, 1875); modal verb.

- The generally received opinion that salt-petre hardens meat, is entirely erroneous (Randolph, 1824); noun.

- A large quantity of fat is used in this recipe, but its extravagance is tempered by the fact that the same fat may be used over and over again until the heating property is exhausted (Lees-Dods, 1886); noun.

- It is essential that the butter should be nearly of the same consistence as the paste, for if too hard it will break in pieces when the paste is rolled, and thus lumps will be formed, and if too soft it will run off (Mrs Toogood, 1866); adjective.

- An eminent physician has discovered that by rubbing wood with a solution of vitriol, insects and bugs are prevented from harbouring there (Copley, 1825); animate.

- Some persons use no sugar which is not clarified, but I think that, for common preserves, such as are usually made in private families, good loaf sugar, not clarified, answers every purpose (Cobbett, 1835); first person singular.

- We have before observed, that a boiled fowl is cut up in the same manner as one roasted. In the representation of this the fowl is complete, whereas in the part of the other it is in part dissected (Haslehurst, 1814); first person plural.

- Ancient prejudice has established a notion, that meat killed in the decrease of the moon, will draw up when cooked (Randolph, 1824); abstract.

- THE advantages of roomy and dry cellaring, are so universally understood, that it seems unnecessary to say much about them (Cobbett, 1835); concealed.

- ...but this you must observe, that when it comes to the carmel height, it will, the moment it touches the water, snap like glass, which is the highest and last degree of refining sugar (Haslehurst, 1814).

- ... it will be a proof that it has acquired the second degree (1814 Haslehurst Priscilla).

- We have before observed, that a boiled fowl is cut up in the same manner as one roasted (Haslehurst, 1814).

- It has been remarked that the insect never returns in future years to those warts of the tree which have been thus treated (Copley, 1825).

- It is certain that very many families, who had previously never thought of brewing their own beer, have been encouraged by the plainness and simplicity of his directions to attempt it, and have never since been without good home-made beer (Cobbett, 1835).

- …but this you must observe, that when it comes to the carmel height, it will, the moment it touches the water, snap like glass, which is the highest and last degree of refining sugar (Haslehurst, 1814).

- I never tried this; but I know that silk pocket handkerchiefs, and deep blue factory cotton will not fade, if dipped in salt and water while new (Mrs Child, 1841).

- Pimpernel is a most wholesome plant, and often used on the continent for the purpose of whitening the complexion; it is there in so high reputation, that it is said generally, that it ought to be continually on the toilet of every lady who cares for the brightness of her skin (A lady of distinction, 1830).

- It may be observed that these breakfast cakes may be prepared in the evening before they are required (Mrs Toogood, 1866).

- Observe, also, that a thick slice should be cut off the meat, before you begin to help your friends, as the boiling water renders the outside vapid, and of course unfit for your guests (Holland, 1825).

- Dredge with flour and salt, baste frequently, and observe that when the MUTTON AND LAMB steam draws towards the fire, the meat is done. Serve with mint sauce (Mrs Bliss of Boston, 1850).

- Some persons, however, say that it is more expensive than buying it. With proper management it cannot be; and, even supposing the cost of the home-baked loaf to be higher, it must be remembered that that of the baker will bear no comparison with it in point of quality (Hooper, 1883).

- Take a cask or barrel, inaccessible to the external air, and put into it a layer of bran, dried in an oven, or of ashes well dried and sifted. Upon this, place a layer of grapes well cleaned, and gathered in the afternoon of a dry day, before they are fall, taking care that the grapes do not touch each other, and to let the last layer be of bran; then close the barrel, so that the air may not be able to penetrate, which is an essential point (Coopley, 1825).

- Instead of butter, many cooks take salad-oil for basting, which makes the crackling crisp; and as this is one of the principal things to be considered, perhaps it is desirable to use it; but be particular that it is very pure, or it will impart an unpleasant flavour to the meat (Beeton, 1875).

- It should not be forgotten that in most cases the ingredient added should be previously cooked, as an omelette remains too short a time over the fire to dress meat or vegetables (Mrs Toogood, 1866).

- PARTICULAR attention is necessary to see that your pots, saucepans, &c. in which you intend to make soup are well tinned, and perfectly free from sand, dirt, or grease; otherwise your soups will be ill-tasted and pernicious to the constitution (Smith, 1831).

- In departing from the usual mode of using either cold water or cold stock, as above, it is to be noted that the boiling water is here used to keep the meat from darkening, which it has a tendency to do (Lees-Dods, 1886).

- Good housekeepers do not need to be told that the best is the cheapest in the end (Hooper, 1883). ).

- An eminent physician has discovered that by rubbing wood with a solution of vitriol, insects and bugs are prevented from harbouring there (Copley, 1825).

- I never tried this; but I know that silk pocket handkerchiefs, and deep blue factory cotton will not fade, if dipped in salt and water while new (Mrs Child, 1841).

- The French, our arbiters in most things of this kind, are of opinion that for each person there should be never less than one dish given; but, generally speaking, it would be more commendable for the caterer to allow, as nearly as possible, one third more dishes than there are convives; for instance, a party of six should have eight dishes appointed them (Hill, 1863).

- Some cooks say, that it will much ameliorate the flavour of strong old cabbages to boil them in two waters, i.e. when they are half done, to take them out, and put them into another sauce pan of boiling water (Randolph, 1824).

- When a carpet is faded, I have been told that it may be restored, in a great measure, (provided there be no grease in it,) by being dipped into strong salt and water (Mrs Child, 1841).

- It may be observed that these breakfast cakes may be prepared in the evening before they are required (Mrs Toogood, 1866).

- If the directions are exactly followed, no one, without being told, could possibly guess that the shad was not fresh from market that morning (Leslie, 1854).

- As the dish is intended for dinner, it must be presumed that there is a substantial and active fire in your stove (Mason, 1871).

- I hope all my readers, whether of a hospitable habit of mind or otherwise, will by this time be convinced that in future they cannot hold themselves justified in making other than a liberal (not to say profuse) display at their desserts (Hill, 1863).

Hyland and Tse (2005a, 2005b) assert that evaluation may be encapsulated in the strategic employment of certain nouns or adjectives within the evaluation segment, as demonstrated by examples (2) and (3). In these instances, the noun evidence and the adjective possible indicate specific degrees of epistemic meaning concerning the entity being evaluated.

Hyland and Tse (2005a; 2005b) classify sentences containing an evaluating matrix and a that-clause in terms of (a) the evaluated entity, (b) the author's stance, (c) the evaluation source and (d) the formal aspect of the offered evaluation. Subsequently, Hyland and Jiang (2018b, pp. 145–146) incorporated additional subcategories, which Alonso-Almeida and Álvarez-Gil (2021a) also included in their analysis of matrices licensing that-clauses in late modern English history texts. According to Hyland and Tse (2005a, p. 46), these clause categories aim to provide 'an interpretation of the writer's claim; of the content of previous studies; of research goals; and of the research methods, models or theories that had been drawn on', as well as 'common or accepted knowledge'; the latter is given in Hyland and Jiang (2018b, p. 146). The authors' perspective is classified into attitudinal and epistemic stances. Attitudinal stance pertains to aspects of affect and obligation, while epistemic stance informs varying degrees of the described event's probability. These categories may indicate propositional truth and accuracy (Hyland & Tse, 2005a, p. 46).

The source of evaluation defines the attribution of information (Hyland & Jiang, 2018b). In the case of humans, this can be the author, expressed as the first person, or a third party, represented as a third-person singular or plural. Alonso-Almeida and Álvarez-Gil (2021a) introduce a third category, i.e. the author and colleagues (we), to denote instances 'in which the subject or subjects of conception may report on subjective or intersubjective meanings' (2021a, p. 230). Additionally, this source of evaluation may encompass entities (e.g. the study shows…) and concealed sources with opaque conceptualisers (e.g. it is often considered…). Hyland and Tse (2005a: 46) suggest that unidentified sources of evaluation may arise from authors' desire to avoid accountability. The evaluative expression category classifies evaluation in the matrix 'according to its form into non-verbal predicates, namely noun and adjectival predicates and verbal predicates, including research acts (e.g. the data show that…), discourse acts (the authors say…), and cognitive acts (the author thinks…)' (Alonso-Almeida & Álvarez-Gil, 2021a, p. 230). Moreover, Kim and Crosthwaite introduced the subcategory of 'anticipation of reader's claim' (2019, p. 5) concerning the evaluative entity. They also further divided Hyland and Tse's subcategory of 'evaluation of research methods, models and theories' (2005b) into the (a) evaluation of methods and (b) evaluation of models, theories and hypotheses, which will not be considered in this paper's analysis of findings.

This examination of findings will focus on matrices from two main perspectives, namely modulation and involvement, irrespective of the entity's nature in the source of evaluation. The modulation will encompass meanings such as probability, possibility, necessity and obligation, among others, while involvement will include categories such as cognitive attribution, inferential, input from observation and input from hearsay. All these aspects will contribute to evaluating the form, meaning and function of stance matrices that license that-clauses.

III. DESCRIPTION OF CORPUS AND METHOD

The data for this study were obtained from the 19th-century sub-corpus of the Corpus of Women's Instructive Texts in English (COWITE19) (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2023). This sub-corpus encompasses texts authored by women to provide readers with specific instructions on performing particular tasks. The version utilised in this research comprises texts gathered until 15 January 2023, all belonging to the recipe genre, as defined by Alonso-Almeida (2013). The primary text type is instructive, as delineated by Werlich (1976). The texts, originating from both print and manuscript sources housed in libraries in the UK and the USA, were digitised and stored as plain text, making them accessible for linguistic software consultation and retrieval.

The compilation adhered to several criteria beyond the fundamental requirement that all texts be instructive. First, the authors had to be women with English as their first language, encompassing both British and American writers. Second, the texts were selected from the earliest available editions, provided that the authors were alive during the nineteenth century and that the books did not constitute new editions or reprints of materials published in the eighteenth century or earlier. Third, the texts had to represent each decade from 1800 to 1899, with roughly equal word counts. Consequently, approximately 50,000 words were collected per decade, with the stipulation that these words originated from more than one source. While texts were gathered from the initial portion of one volume, the subsequent set of texts was taken from the latter part of another volume within the same decade. This approach ensured the avoidance of repetition and enhanced the representativeness of the corpus. The content of COWITE19 encompasses culinary, medical and pharmaceutical information, among other topics.

The following table provides further details on COWITE19:

Table 1. The Corpus of Women's Instructional Writing in English: Nineteenth-Century Subcorpus, COWITE19.

| Files | Tokens | Types | Lemmas |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | 487,136 | 12,142 | 15,374 |

In this study's methodology, the corpus underwent part-of-speech (POS) tagging to facilitate complex computational searches using CasualConc software developed by Imao. This process allowed for identifying all instances of stance matrices licensing that-clauses in the corpus, focusing on specific searches as prepositions or subordinating conjunctions with other word categories. It is acknowledged that this approach may overlook matrices not preceding that; however, the omission of that in written texts bears little significance, as noted by Hyland and Tse (2005b, p. 130). The findings from the corpus investigation were transferred to an Excel spreadsheet, providing a 50-word context on both the left and right sides, ensuring that matrices could be accurately described and categorised based on form, meaning and function. Consequently, this methodology enabled the integration of statistical results with qualitative interpretations.

IV. RESULTS

The analysis of stance matrices that license that-clauses reveals preferences in terms of structure, meanings and functions exhibited. Despite the instructional text type's inherent nature, which tends to focus on direct orientation and seemingly limits the use of complex structures and evaluative language, the findings indicate that this is not always the case, as detailed in the subsequent subsections. The corpus contains a total of 355 matrices, each with a specific distribution concerning the variables of forms, meanings and functions.

IV.1. Forms

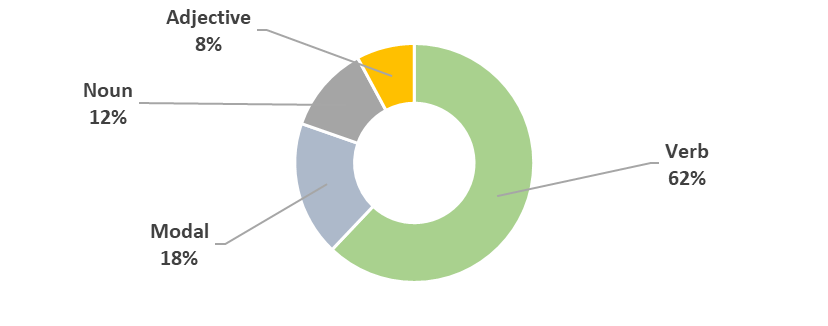

In terms of forms, matrices that license that-clauses may convey evaluative, perspectivising or legitimising meanings by emphasising certain devices: word categories and the presence of a syntactic subject. In relation to word categories, stance matrices are classified into nouns, adjectives, verbs and modal verbs, depending on their role in conveying stance meaning. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of stance matrices licensing that-clauses in COWITE19, categorised by word categories.

Figure 1. Distribution of stance matrices licensing that-clauses in terms of word categories.

The 'verb' category accounts for the vast majority of matrices, constituting 62% of instances, utilised to convey various stance meanings. Following this, modal verbs represent 18%, nouns 12% and adjectives 8%. Some examples of these stance matrices are provided below.

As observed in these examples, verbal forms may exhibit various tenses or moods, such as the present tense in (4) and (5) and the imperative in (6). Modal verbs also feature in these texts, as demonstrated in the instance (7), with should. The nouns preceding clauses in (8) and (9) serve functions such as implicature and politeness, respectively, which will be explicated later in this paper. The final example (10) depicts an adjective preceding a that-clause, where the matrix's structure is designed to convey a modal meaning of necessity in relation to the information presented in the subordinate clause.

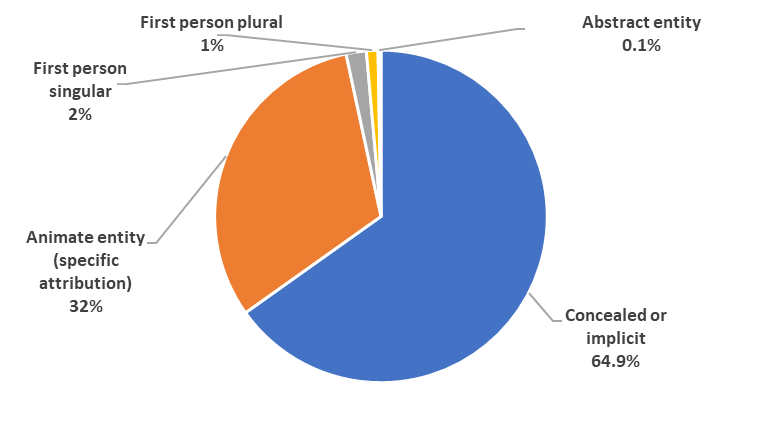

Concerning syntactic subjects, they may offer insights into aspects of involvement and commitment towards the information presented. The corpus exhibits various syntactic realisations, including concealed or implicit entities (where the source of conceptualisation is absent or unidentified), animate entities indicating specific attribution (incorporating pronouns other than 'I' and 'we'), first-person singular, first-person plural and abstract entities. These realisations are provided in the order of frequency, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Realisations of syntactic subjects

Concealed conceptualisers and/or syntactic subjects emerge as the most prevalent type in COWITE19, accounting for 65% of the analysed matrices, the reasons for which will be elucidated. This type is succeeded by animate entities, constituting 32% of the instances. First-person singular and plural pronouns follow, with a 2% and 1% distribution, respectively. The single case of a subject realised by abstract entities renders it an outlier. The examples below demonstrate these subject types in COWITE19:

Identifying these matrices is crucial for understanding their functions, as they may convey information regarding conceptualisers and the author's degree of involvement in developing information, among other aspects. Indeed, this information is necessary for the qualitative interpretation of the matrices, as the combination of the categories addressed in this study yields specific evaluative interpretations, particularly in terms of modulation and involvement. The instance in (11) demonstrates that the information is intersubjectively construed; however, the semantics of the verbal phrase entails this, as the syntactic subject (i.e. the advantages of roomy and dry cellaring) does not disclose any specific conceptualiser, and no agent is provided. Instance (12) presents a case of an animate syntactic subject (i.e. an eminent physician) to whom the information in that that-clause is entirely attributed. The use of "I" and "we" in (13) and (14) reflects subjective and intersubjective conceptualisers, respectively, and these resolve into meanings concerning the authors' involvement in the informative quality of the proposition. This may also impact the authors' degree of commitment to propositional truth. Finally, (15) displays a case of an abstract entity (i.e. ancient prejudice), which refers to shared knowledge, and this, coupled with the abstract noun preceding the that-clause (i.e. notion), may underscore a lack of involvement concerning the inception of information. All of these factors may contribute to interpreting the entire matrix in terms of discourse politeness (cf. Brown & Levinson, 1987).

IV.2. Meanings

The stance matrices licensing that-clauses, as identified in the COWITE19 corpus, encompass a range of meanings, including possibility, probability, certainty, inferential, obligation, necessity, volition, input derived from observation or hearsay and attribution (both communicative and cognitive). Table 1 presents the distribution of matrices corresponding to these values within the corpus.

Table 2. Percentage distribution of stance matrices licensing that-clauses according to the variable of meaning.

| Meaning | Count | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Obligation | 55.18% | Modal, deontic |

| Necessity | 16.25% | Modal, deontic |

| Input from observation | 9.52% | Evidential, experiential |

| Communicative (others) | 6.16% | Evidential, communicative |

| Cognitive attribution (others) | 3.64% | Evidential, cognitive |

| Input from hearsay | 2.80% | Evidential, communicative |

| Possibility | 1.68% | Modal, epistemic |

| Certainty | 1.68% | Modal, epistemic |

| Cognitive attribution (self) | 1.12% | Evidential, cognitive |

| Inferentiality | 0.84% | Inference, cognitive |

| Probability | 0.84% | Modal, epistemic |

| Volition | 0.28% | Modal, epistemic |

Table 2 demonstrates that obligation is the most prevalent meaning in the examined matrices, followed by necessity and first-hand evidence, which include observational input. Subsequently, evidentials based on third parties – such as communicative others, cognitive attribution (others), and hearsay – appear in descending order of frequency. The least frequent meanings involve epistemic categories like 'possibility, certainty, cognitive attribution (self), inferentiality, probability and the affective category of volition'.

These examples further indicate a general tendency in COWITE19 to convey information through stance-taking devices that demonstrate the author's unambiguous authority on the subject, as seen in (16) and (17), and legitimise their opinions based primarily on first-hand evidence, as in (18) or third parties, as in (19). The highly pedagogical tone of the texts and the authors' intention to showcase their expertise may account for the use of these strategies. Consequently, a sense of factuality is evident, which could also explain the few instances of epistemic devices related to probability, certainty and cognitive evidentiality found in this compilation. Example (20) exemplifies a matrix expressing certainty.

IV.3. Functions

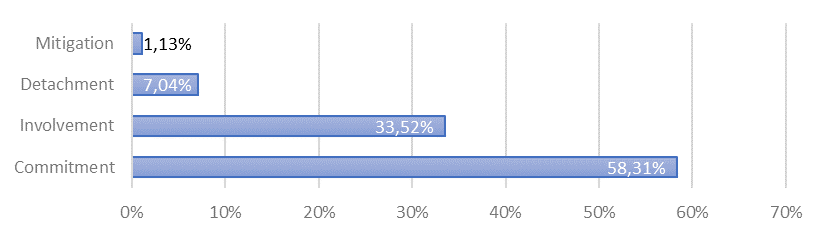

My analysis of stance matrices licensing that-clauses has also isolated a number of functions associated with these devices, with the results provided in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Percentage distribution of stance matrices licensing that-clauses according to their main function.

The notion of commitment frequently appears in instructional texts, accounting for approximately one-third of cases. Notably, the concepts of attenuation and detachment are only identified in just over 8% of instances, with attenuation being the least prominent. Consider the following examples:

Example (21) demonstrates the concept of commitment, manifested in the use of the modal of obligation must, which modulates the experiential verb observe, ultimately reflecting the author's confidence in the provided information. In (22), the cognitive matrix conveys the author's subjective contribution to the information within the that-clause. In contrast, example (23) utilises the intersubjective communicative evidential 'is said generally, that' to indicate a lack of involvement concerning the proposition within the subordinating clause. Lastly, example (24) represents a case of mitigation, as evidenced by the use of may.

V. DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

The presented results reveal the prominent use of stance matrices licensing that-clauses in COWITE19 to assess the information within the subordinated clause. As previously noted, these matrices serve primary functions, which can be categorised into four main groups. These groups emphasise aspects related to the authors' modulation or involvement concerning the content to clarify the author's perspective on what is described in the subordinated clause. These primary functions give rise to several pragmatic interpretations of these matrices, including authority, persuasion, negative politeness, impoliteness and positive politeness.

Conveying authority is the most frequent pragmatic function identified in our corpus, accounting for 71.75% of cases, particularly relevant in the context of instructive writing. The expression of authority may, in turn, be indicative of reliable information, as exemplified in the following example:

In example (25), authority is established through the imperative mood, indicating a required action and the need for caution. This enables the author to demonstrate and emphasise her expertise, thereby increasing the reader's trust. Although the imperative mood suggests a hidden conceptualiser, the conveyed subjective meaning reflects the authors' commitment to their texts. Commitment-associated meanings include obligation and necessity, often with a concealed or implicit conceptualiser, and occasionally, specific attributions to animate entities or, less frequently, first-person singular entities. This is evident in the following sentences, where the qualifying or stance feature is encoded in the verbal tense or lexical items such as verbs (26), modals (27), nouns (28) and adjectives (29):

In (26), the verb observe serves as an effective stance strategy, as the author explicitly demands a specific response from the reader. While the imperative usage is typical in recipe genres, this experiential verb distinguishes itself from others more closely related to culinary practices. A similar intention appears in (28).

In (27), an implicit conceptualiser is introduced using a cleft sentence, focusing on the cognitive event, i.e. remember, modulated by the deontic modal verb must. Interestingly, the entire passage remains within an argumentative thread, employing the inferential form supposing to justify the earlier counterargument it cannot be in response to the intersubjective claim introduced earlier, i.e. some persons, however, say that it is more expensive than buying it. The author weaves the text using a series of arguments based on authoritative knowledge, culminating in the effective strategy must be remembered, which is softened by the aforementioned inferential as a negative politeness strategy.

Finally, in (29), be particular that results from the earlier reference to unknown cooks using salad oil for basting. The author provides precise understanding through a series of effective stance strategies, including to be considered, it is desirable to and be particular, before offering the justification for her claim, i.e. or it will impart an unpleasant flavour. These sequences consistently communicate the intention to convey authoritative guidance by asserting reliability claims, seemingly rooted in the author's expertise and, at times, declared experience.

Authority is manifested through matrices conveying necessity, achieved through modal verbs, as illustrated in (30); adjectives suggesting modality, as shown in (31); deontic structures, such as to be to + infinitive, as in (32); and lexical verbs, as demonstrated in (33).

Authority is evident in matrices attributing information sources, such as in (34), and subjective cognitive expressions, such as in (35). The overt manifestation of involvement signals the authors' expertise in these cases.

Matrices indicating source or mode of knowledge are also employed to suggest persuasion, as demonstrated in the examples below:

In these instances, the use of attribution, such as a cognitive source in (36) and a communicative source in (37), aims to convince readers by presenting the viewpoints of third parties, which may be considered authorities. In (36), a parenthetical emphasises the significance of the French culinary tradition: The French, our arbiters in most things of this kind. The communicative evidential phrase I have been told that in (38) features an opaque conceptualiser; however, the overall impression suggests that this structure is intended to persuade the reader of the assertion's truth, even if the attribution also implies a degree of authorial detachment, as she is not responsible for the claim.

The function of the matrices described above is closely related to the expression of negative politeness to avoid imposition, which is also evident in the use of epistemic modals or inferential devices, as illustrated below:

These examples demonstrate the use of epistemic modals, such as may in (39) and could in (40), to provide information while avoiding the imposition of perspective. The epistemic adverb, possibly, in (40) contributes to hedging the proposition, mitigating its illocutionary force, as highlighted by Álvarez-Gil (2018, p. 49), in contrast to other factual adverbs in the realm of certainty (cf. Álvarez-Gil, 2019). Similarly, the modal of epistemic necessity must modulates the passive construction be presumed that (41), denoting a sense of politeness by suggesting the manner in which the information has been elaborated, allowing readers to evaluate and agree on the quality and verisimilitude of the information for themselves.

The use of matrices that emphasise an authoritative stance can also convey impoliteness, even if unintended, as demonstrated in the following example:

In (42), the phrase will be convinced by this time reveals a degree of overt authorial imposition on the readers to meet the author's expectations. Interestingly, the condescending tone, already evident in the stance-taking device I hope and reinforced by whether of a hospitable habit of mind or otherwise, accentuates the author's power, encroaching on the readers' space in multiple ways (cf. Alonso-Almeida & Álvarez-Gil, 2021b; Culpeper, 2012).

VI. CONCLUDING REMARKS

This article presents research conducted using evidence from COWITE19 and addresses the questions posited in the introduction. The findings demonstrate how nineteenth-century stance matrices, which license that-clauses, convey interpersonal meanings related to the authors' perspectives and involvement with the information in the accompanying that-clauses. The study reveals that the matrices' structure aligns closely with the semantic meanings they encode, allowing for the communication of pragmatic meanings, such as authority, persuasion and politeness, in the analysed instructive texts.

Regarding form, the most frequently observed stance features in the matrices are verbs in their corresponding tenses, followed by modal verbs, nouns and adjectives. Syntactic subjects constitute another significant feature, as they may indicate varying degrees of reliability when evaluating statements. The most common strategies involve concealed or implicit entities and animate entities with specific attributions of information. First-person pronouns are analysed separately to assess the authors' self-reported involvement in the information development.

In terms of meaning, the majority of matrices exhibit strategies conveying a sense of obligation alongside first-hand evidential strategies, revealing a distinct evaluation of the texts. Epistemic modals and communicative and cognitive evidentials are utilised to express varying degrees of certainty and factuality. This aspect correlates strongly with the functions of the matrices identified in COWITE19. Four primary functions are recognised with these devices: commitment, involvement, detachment and mitigation. These inform the pragmatic functions of 'authority, persuasion and (im)politeness', with authority being the most prominent.

The results contribute to existing research on earlier women's writing, aiming to discern whether it exhibits a unique voice with distinguishable rhetorical strategies in the development, attribution and representation of the meaning or whether it adheres to contemporary technical and scientific writing styles. The size of COWITE19 suggests a high degree of representativeness in the results presented herein. However, this study is limited by the absence of a comparison to a corpus of texts authored by men, which is planned for future research to unveil potential gender differences.

VII. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research conducted in this article has been supported by the Plan Estatal de Investigación Científica, Técnica y de Innovación 2021–2023 of the Ministerios de Ciencia e Innovación under award number PID2021-125928NB-I00, and the Agencia Canaria de investigación, innovación y sociedad de la información under award number CEI2020-09. We hereby express our thanks.

VIII. REFERENCES

Abdollahzadeh, E. (2011). Poring over the findings: Interpersonal authorial engagement in applied linguistics papers. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(1), 288-297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.019

Alonso-Almeida, F. (2013). Genre conventions in English recipes, 1600–1800. In M. DiMeo & S. Pennell (Eds.) Reading and writing recipe books, 1550–1800 (pp. 68-92). Manchester University Press. https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526129901.00011

Alonso-Almeida, F. (2015). On the mitigating function of modality and evidentiality. Evidence from English and Spanish medical research papers. Intercultural Pragmatics, 12(1), 33-57. https://doi.org/10.1515/ip-2015-0002

Alonso-Almeida, F. and Álvarez-Gil, F. J. (2021a) Evaluative that structures in the Corpus of English Life Sciences Texts. In: I. Moskowich, I. Lareo, and G. Camiña (Eds.), “All families and genera.” Exploring the Corpus of English Life Sciences Texts (pp. 228-247). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.237.12alo.

Alonso-Almeida, F. & Álvarez-Gil, F. J. (2021b) Impoliteness in women’s specialised writing in seventeenth-century English. Journal of Historical Pragmatics, 22(1), 121–152. https://doi.org/10.1075/jhp.20004.alo.

Alonso-Almeida, F. & Carrió-Pastor, M. L. (2019). Constructing legitimation in Scottish newspapers: The case of the independence referendum. Discourse Studies, 21(6), 621-635. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445619866982.

Alonso-Almeida, F., Ortega-Barrera, I., Álvarez-Gil, F., Quintana-Toledo, E. & Sánchez-Cuervo, M. (Eds.) (2023). COWITE19= Corpus of Women’s Instructive Writing, 1800-1899. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

Álvarez-Gil, F. J. (2018). Adverbs ending in -ly in late Modern English. Evidence from the Coruña Corpus of History English texts. Universidad Politécnica de Valencia.

Álvarez-Gil, F. J. (2022). Stance devices in tourism-related research articles: A corpus-based study. Peter Lang Verlag. https://doi.org/10.3726/b20000.

Álvarez-Gil, F. J. (2019) An analysis of certainly and generally in Late-Modern English English history texts. Research in Language 17 (2), 179-195. https://doi.org/10.2478/rela-2019-0011.

Beeton, M. (1875). The Englishwoman’s cookery book: being a collection of economical recipes taken from her “Book of household management”. Ward, Lock, and Co.

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S. & Finegan, E. (1999). Longman grammar of spoken and written English. Longman.

Brown, P. & Levinson, S. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press.

Caffi, C. (2007). Mitigation. Elsevier.

Campbell, H. (1893). In foreign kitchens: with choice recipes from England, France, Germany, Italy, and the North. Robert Brothers.

Carrió-Pastor, M. L. (2012). A contrastive analysis of epistemic modality in scientific English. Revista de lenguas para fines específicos, 18, 115-132.

Carrió-Pastor, M. L. (2014). Cross-cultural variation in the use of modal verbs in academic English. SKY Journal of Linguistics, 27 (1),153–166

Carrió-Pastor, M. L. (2016). Mitigation of claims in medical research papers: A comparative study of English- and Spanish-language writers. Communication and Medicine, 13 (3), 249-261. https://doi.org/10.1558/cam.28424.

Chafe, W. (1986). Evidentiality in English conversation and academic writing. In W. Chafe & J. Nichols (eds.), Evidentiality: The linguistic coding of epistemology (pp. 261-272). Ablex.

Charles, M. (2007). Argument or evidence? Disciplinary variation in the use of the Noun that pattern in stance construction. English for Specific Purposes, 23, 203-218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2006.08.004.

Child, L. M. (1841). The American Frugal Housewife: Dedicated to Those who are Not Ashamed of Economy. Samuel S. & W. Wood.

Clift, R. (2006). Indexing stance: Reported speech as an interactional evidential. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 10(5), 569-595. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2006.00296.x.

Cobbett, A. (1835). The English Housekeeper: Or, Manual of Domestic Management, Etc. Anne Cobbett.

Copley, E. (1825). The cook’s complete guide, on the principles of frugality, comfort, and elegance: including the art of carving and the most approved method of setting-out a table, explained by numerous copper-plate engravings: instructions for preserving health and att. George Virtue.

Culpeper, J. (2011). Impoliteness: Using language to cause offence. Cambridge University Press.

Cust, M. A. B. L. (1853). The invalid’s own book: a collection of recipes from various books and various countries by the honourable Lady Cust. D. Appleton and Company.

Distinction, A L. of. (1830). The Mirror of the Graces: Or, The English Lady’s Costume. Containing General Instructions for Combining Elegance, Simplicity, and Economy with Fashion in Dress; Hints on Female Accomplishments and Manners; and Directions for the Preservation of Health and Beauty. A. Black.

Estellés, M. & Albelda Marco, M. (2018). On the dynamicity of evidential scales. In C. Bates Figueras and A. Cabedo Nebot (Eds.), Perspectives on evidentiality in Spanish. Explorations across genres (pp. 25-48). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.290.02est.

Fox, B. A. (2008). Evidentiality: Authority, responsibility, and entitlement in English conversation. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 11, 167-92. https://doi.org/10.1525/jlin.2001.11.2.167.

Halliday, M. & Matthiessen, C. (2014). An introduction to functional grammar. Taylor & Francis.

Haslehurst, P. (1814). The family friend, and young woman’s companion; or, housekeeper’s instructor: containing a very complete collection of original and approved receipts in every branch of cookery, confectionery, &c. &c. C. & W. Thompson.

Hill, G. (1863). The Lady’s Dessert Book: A Calendar for the Use of Hosts and Housekeepers, Containing Recipes, Bills of Fare, and Dessert Arrangements for the Whole Year. Richard Bentley.

Holland, M. (1825). The complete economical cook and frugal housewife. T. Tegg.

Hooper, M. (1883). Every day meals: being economic and wholesome recipes for breakfast, luncheon, and supper. Kegan Paul, Trench.

Hyland, K. (1998). Hedging in scientific research articles John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Hyland, K. (2005a). Stance and engagement: A model of interaction in academic discourse. Discourse Studies, 7(2), 173-192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445605050365.

Hyland, K. (2005b). Metadiscourse. Exploring interaction in writing. Continuum.

Hyland, K & Jiang, F. K. (2018a). “In this paper we suggest”: Changing patterns of disciplinary metadiscourse. English for Specific Purposes, 51, 18-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2018.02.001.

Hyland, K. & Jiang, F. K. (2018b). ‘We Believe That … ’: Changes in an Academic Stance Marker. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 38(2), 139-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/07268602.2018.1400498.

Hyland, K. and Tse, P. (2005a). Evaluative that constructions: Signalling stance in research abstracts. Functions of Language, 12(1), 39-63. https://doi.org/10.1075/fol.12.1.03hyl.

Hyland, K. & Tse, P. (2005b). Hooking the reader: A corpus study of evaluative that in abstracts. English for Specific Purposes, 24(2), 123-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2004.02.002.

Jalilifar, A, Hayati, S. & Don, A. (2018). Investigating metadiscourse markers in book reviews and blurbs: A study of interested and disinterested genres. Studies About Languages, 33, 90-107. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.sal.33.0.19415.

Johnstone, B. (2009). Stance, style, and the linguistic individual. In A. Jaffe (Ed.), Stance: sociolinguistic perspectives (pp. 29-71). Oxford University Press.

Kendall, K. (2004). Framing authority: Gender, face, and mitigation at a radio network. Discourse and Society, 15(1), 55-79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926504038946.

Kim, C. & Crosthwaite, P. (2019). Disciplinary differences in the use of evaluative that: Expression of stance via that-clauses in business and medicine. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 41, article 100775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2019.100775.

Langacker, R. W. (2009) Investigations in cognitive grammar. Mouton de Gruyter.

Lees-Dods, M. (1886). Handbook of practical cookery: with an introduction on the philosophy of cookery. T. Nelson and Sons.

Leslie, E. (1854). New Receipts for Cooking. T. B. Peterson.

Marín-Arrese, J. I. (2011). Epistemic legitimizing strategies, commitment and accountability in discourse. Discourse studies, 13(6), 789-797. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445611421360c.

Martin, J. (2000). Beyond exchange: APPRAISAL systems in English. In S. Hunston and G. Thompson (Eds.), Evaluation in text: authorial stance and the construction of discourse (pp. 142-175). Oxford University Press.

Mrs. Bliss of Boston. (1850). The Practical Cook Book: Containing Upwards of One Thousand Receipts. Lippincott, Grambo & Co.

Mason, M. A. B. (1871). The Young Housewife’s Counsellor and Friend: Containing Directions in Every Department of Housekeeping, Including the Duties of Wife and Mother. J.B. Lippincott & Company.

Mauranen, A. & Bondi, M. (2003). Evaluative language use in academic discourse. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 2 (4), 269-271. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1475-1585(03)00045-6.

Randolph, M. (1824). The Virginia house-wife. Davis and Force.

Smith, P. (1831). Modern American Cookery ... With a list of family medical recipes, and a valuable miscellany. J. & J. HARPER.

Stotesbury, H. (2003). Evaluation in research article abstracts in the narrative and hard sciences. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 2 (4), 327-341. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1475-1585(03)00049-3.

Toogood, H. (1866). Treasury of French Cookery: A Collection of the Best French Recipes Arranged and Adapted for English Households. Richard.

Werlich, E. (1976). A text grammar of English. Quelle and Meyer.

Wetherell, M. (2013). Affect and discourse–What’s the problem? From affect as excess to affective/discursive practice. Subjectivity, 6 (4), 349-368. https://doi.org/10.1057/sub.2013.13.

Received: 13 March 2023

Accepted: 27 May 2023