Contrastive relational markers in women’s expository writing in nineteenth-century English

Margarita Esther Sánchez Cuervo

margaritaesther.sanchez@ulpgc.es

Discourse, Communication and Society Research Group

Departamento de Filología Moderna, Traducción e Interpretación,

Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain

ABSTRACT

This study seeks to analyse the occurrence of contrastive relational markers in a corpus of recipes called Corpus of Women’s Instructive Texts in English, the 19th century sub-corpus (COWITE19). Opposition relations, also referred to as adversative or contrastive, are usually identified with markers such as “but”, “although”, and “however”. From a semantic point of view, a classification of these relations can be established as contrast, concession, and corrective, based on their linguistic evidence, lexical differences and syntactic behaviour (Izutsu, 2008). A further rhetorical function is antithesis, presented as a consistent device possessed of a verbal, analytical and persuasive nature (Fahnestock, 1999). The analysis of these markers is made following a computerised corpus analysis methodology and aims to discern which contrastive markers are mostly employed for the instructions conveyed by females. It also shows which opposition relation is predominant, whether contrastive, concessive, or corrective. Finally, it detects antithesis as an additional opposing meaning. In all cases, the possible argumentative role of these markers is highlighted as another step in the characterisation of women’s scientific writing.

Keywords: opposition; contrastive; concessive: corrective; antithesis.

I. INTRODUCTION

This article seeks to identify and analyse the main contrastive relations in the corpus of recipes called Corpus of Women’s Instructive Texts in English, the 19th century sub-corpus, hereafter COWITE19 (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2023). The sub-corpus comprises texts written by women which detail the preparation of multiple recipes. For this research, the author has focused on the period which covers the timespan between 1806 and 1849. Recipes can be broadly defined as a list of steps that are followed, for example, in a culinary or medical procedure, and that are usually organised by a series of guiding instructions during their preparation. As a genre, the recipe is described by its external features, bearing in mind the purpose of this activity in which the writers of recipes engage as members of our culture (Martin, 1984, p. 25). As a text-type, in contrast, the recipe is explained by means of its internal linguistic criteria, that is, its morphological, syntactic and lexical characteristics, so it can be mainly developed as an expositive or instructive text-type (Alonso-Almeida & Álvarez-Gil, 2020, pp. 64-65; Biber, 1988). Some of these linguistic features comprise the use of contrastive discourse markers which signal the basic relation of opposition between discourse segments.

In this study, broad consideration will be given to Izutsu’s (2008, pp. 648-649) research on three semantic categories of opposition relations: contrast, concessive, and corrective, which are mostly derived from Cognitive Grammar (Langacker, 1987, 1991). It is a model which offers an analysis of each semantic category, and it is suitable for the corpus under study. Izutsu (2008, p. 647) acknowledges that most studies concerning opposition relations base their argument on the dichotomy which exists between the contrast and concessive dichotomy (Blakemore, 1987, 1989; Kehler, 2002; Lakoff, 1971; Spooren, 1989) and the corrective and non-corrective dichotomy (Abraham, 1979; Anscombre & Ducrot, 1977; Dascal and Katriel, 1977; Foolen, 1991; Lang, 1984; von Klopp, 1994; Winter & Rimon, 1994). As will be seen in the results of the corpus study, the concessive dichotomy is the most repeated, mainly expressed by the coordinating conjunction ‘but’.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

The study of opposition relations includes a variety of terms like contrastive, concessive, and adversative. Grammars such as Greenbaum and Quirk’s A Student’s Grammar of the English Language (1990, p. 186) include the following names regarding the semantics of conjuncts under the umbrella of contrastive meanings:

- ) “reformulatory” and “replacive” in examples like “She’s asked some of her friends – some of her husband’s friends, rather”;

- ) “antithetic”, as in “They had expected to enjoy being in Manila but instead they both fell ill”;

- ) “concessive”, as in “My age is against me: still, it is worth a try”.

Lyons (1971) distinguishes between two uses of “but”: semantic opposition, in cases such as “John is tall, but Bill is short”, and denial of expectation, as in “John is tall, but he’s no good at basketball”, which could be paraphrased as the concessive “Although John is tall, he’s no good at basketball”. As to the relation of contrast, it has been typically marked as paratactic in terms of functional grammar through the relationship of enhancement, in which one clause enhances the meaning of another by employing a number of possible expressions which cover the references to time, place, manner, cause and condition (Halliday, 1985, pp. 232-239).

From a pragmatic perspective, the connection of contrast can be conveyed by using a varied scale of expressions. For Rudolph (1996, pp. 27-28), this particular connection indicates that there is a relationship between two contrastive states of affairs and the speaker’s opinion of that relationship. In the example “He needed the money, but I did not lend him any”, the author explains that one person is in need and the second person is expected to answer to that need; however, the second person decides not to help him. A “but” sentence seems to be a logical contrastive expression, however, without using that conjunction, the interpretation is still the same: “He needed the money. I did not lend him any”. Likewise, in the sentence “Although he needed the money, I did not lend him any”, the author admits another form of contrast with the semantic value of concession. In all of the examples, there is a causal constant that alludes to the fact that one person is in need and the other is expected to help him, but he/she does not. As a result, the causal chain that should naturally occur in these cases is broken and the expectation of help is not fulfiled. Rudolph (1996, pp. 32-39) adds that connective expressions are signs for the hearer/listener to help him/her decode the speaker’s utterance, whereas for the speaker, those expressions become instruments to give his/her personal views. Rudolph also makes a difference between simple and complex adversative and concessive connectives by including “but”, “although” and “however” within simple connectives. In contrast, complex connectives are made of two or more lexical items that receive their new contrastive meaning in the act of composition and function. “Nevertheless” and “even if” comprise an instance of complex adversative and concessive linkers respectively.

In a similar vein, Sweetser (1990, p. 76) claims that conjunctions as logical operators must be studied not only from a lexical-semantic analysis, but from “the context of an utterance’s polyfunctional status as a bearer of content, as a logical entity, and as the instrument of a speech act”. In a study of “but”, the scholar (Sweetser, 1990, p. 103) argues that many examples might be connected with “real-world” clash or contrast. Sweetser establishes a difference in cases like “John eats pancakes regularly, but he never keeps any flour or pancake mix around” and “John is rich but Bill is poor”. In the first case there seems to be a clash in the real world because the causal sequence that implies that John should keep flour if he is a pancake-eater is disrupted; in the second there is indeed a contrast, in that we can believe that there is no clash in John being wealthy and Bill being destitute since both rich and poor people exist simultaneously in the real world. A further vision of contrast is seen in Thompson et al. (2007, pp. 262-263), who include concessive clauses as a subtype of adverbial clauses. “Concessive” is discussed as a general term for a clause establishing a concession against which the proposition in the main clause is contrasted. According to this concept, definite concessive clauses are considered, which are marked by a subordinator like “although”, “even though”, or “except that”, and can be paraphrased by inserting “in spite of the fact that…”; and indefinite concessive clauses, which indicate a meaning such as “no matter what” or “whatever”. They are usually expressed by means of an indefinite pronoun as in “Whoever he is, I’m not opening that door”.

II.1. Izutsu’s model of opposition relations

Izutsu (2008, pp. 656-671) organises opposition relations into three distinct semantic categories: contrast, concessive and corrective, which are illustrated by the following examples:

- ) Contrast

- John is rich, but Tom is poor.

- I’ve read sixty pages, whereas she’s read only twenty.

- John likes math, Bill likes music, while Tom likes chemistry.

- ) Concessive

- Although John is poor, he is happy.

- Bill studied hard, but he failed the exam.

- We thought it would rain; nevertheless, we went for a walk.

- ) Corrective

- John is not American but British.

- Ann doesn’t like coffee – she likes tea.

- My grandmother died in 1978, (and) not 1977.

This classification of semantic relations was already discussed by Foolen (1991), who categorised them as “semantic opposition” (contrast), “denial of expectation” (concessive) and “correction” (corrective). Foolen regards these differences as pragmatic or “polyfunctional” rather than semantic, whereas Izutsu deems that these categories can be disambiguated regardless of the context where the sentence occurs and, as a result, they are not pragmatically ambiguous but semantically distinct from one another.

Izutsu examines the semantic categories of opposition by considering the following four factors:

- The mutual exclusiveness of different compared items (CIs) in a shared domain.

- The number and type of compared items (CIs).

- The involvement of an assumption/assumptions.

- The validity of segments combined.

Izutsu (2008, p. 656) explains that the compared items (CIs) are to some extent different and are supposed to belong to “mutually exclusive regions in a shared domain”. The second factor has to do with the number of contrasted items in a comparison, and with whether the CIs are explicitly distinguished or, by contrast, this fact is not clear enough in each sentence. The third factor focuses on whether there are one or more assumptions involved in the meaning of the opposition which show that some information is inferred by the speaker at the time of speaking. Finally, the fourth factor is related to whether the semantic content of each segment linked by a connector is accepted as valid or invalid by the speaker. A segment is defined here as a term made up of several sizes of connected units, be it a word, phrase, clause, sentence, or a stretch of discourse.

II.1.1. Contrast

This first relation is defined as a simple opposition between the propositional contents of two symmetrical clauses. The change of meaning is not clear after the order of clauses is reversed, and the inclusion of the “and” linker does not entail a significant variation either. This relation should have the following characteristics:

- Different compared items (CIs).

- A shared domain.

- The mutual exclusiveness of different CIs.

The term domain or cognitive domain has to do with “a context for the characterisation of a semantic unit”, according to Langacker (1987, p. 147). The following example contains explicitly different CIs (“John” and “Tom”), which are compared in terms of the same domain and size, and show mutual exclusiveness, “small” vs. “big”.

- ) John is small, but Tom is big.

- )

- D-concessive: Although John is poor, he is happy.

- I-concessive: The car is stylish and spacious, but it is expensive.

II.1.2. Concessive

The second relation comprises some background assumption or expectation. Izutsu determines two types of concessive: direct (D-concessive) and indirect (I-concessive). For example:

The direct concessive implies an assumption which is inferentially drawn from the propositional content of the first segment. The sentence above “Although S1, S2” is formulated as follows: “If S1, (then normally) not S2”. Sentence (5a) inferentially invokes an assumption as given in (6a).

- “If John is poor, (then normally) he is not happy”.

Unlike contrast, D-concessive sentences do not indicate a mutually exclusive relation between the propositional contents of clauses. In sentence (5a), “poor” and “happy” do not belong to the same shared domain. However, what is mutually exclusive in the example can be found between the propositional content of the second clause (“he is happy”) and an assumption evoked from the first clause (“he is not happy”). D-concessive sentences can be thus described in this way:

- Two different compared items (CIs) occupy mutually exclusive regions in a shared domain.

- The compared items (CIs) are two different tokens of the identical entity with one in an assumption and the other in the propositional content.

- The relevant assumption is formulated as “If S1, (then normally) not S2”.

The term “token” is interpreted here as “each occurrence of an entity in mind for the understanding of a connected utterance” (Izutsu, 2008, p. 662). This description of D-concessive also applies to examples with final concessive clauses.

In the case of I-concessive, the assumption “If S1, (then normally) not S2” does not apply because there is a mutually exclusive relation between two assumptions deriving from S1 and S2, and not an assumption being drawn from S1 and the propositional content of S2. A further characteristic of this concessive is that the compared items (CIs) are two different tokens of the identical entity, each one being evoked as a part of a different assumption.

Izutsu follows Azar’s (1997, p. 310) explanation that the clauses of this indirect concessive sentence are oriented towards two opposite conclusions, in that S1 leads to a non-stated conclusion (C), and S2 leads to the rejection of that conclusion (~C). She offers the following interpretation from the example (5b) above:

- “If the car is stylish and spacious, we should buy it”. “If S1, (then normally) C”.

- “If the car is expensive, we should not buy it”. “If S2, (then normally) not C”.

In this I-concessive sentence, a mutually exclusive relation exists between two assumptions. The CIs are two different tokens of an identical entity, with one evoked as part of assumption (7a) and the other evoked as part of assumption (7b). Furthermore, the entity involved in the mutually exclusive relation is not a thing (like “we”, “the car”), but the relation of “our buying the car”. In summary, the I-concessive can be described as follows:

- Two different compared items (CIs) occupy mutually exclusive regions in a shared domain.

- The compared items (CIs) are two different tokens of the identical entity with each evoked as a part of a different assumption.

- The relevant assumptions are formulated as “If S1, (then normally) C” and “If S2, (then normally) not C”.

II.1.3. Corrective

The third relation conveys denial, that is, “rejection of previously made statement (or previously held belief as recognised by the speaker)” (Dacal & Katriel, 1977, p. 161). The corrective interpretation is made where “but” combines two noun phrases and not two full clauses, in which case the meaning is concessive. For example:

- He likes not coffee but tea.

- “He likes not S1 [coffee] but S2 [tea]”.

In sentence (8a), the negation entails a denial of a previous assertion or implication. The first segment (S1) shows an invalid result and anticipates a valid alternative to S1. However, the negation in (8b) is propositional negation and is part of a propositional content, so it is used for making a negative assertion. (8b) affirms the validity of S1 (the negative proposition) and also the validity of S2 (the positive proposition).

The corrective meaning can be summarised following this pattern:

- Two different compared items (CIs) occupy mutually exclusive regions in a shared domain.

- The compared items (CIs) are two different tokens of the identical entity before and after removal/relocation.

II.1.4. Antithesis

This study also examines the relationship of antithesis as a further type of semantic opposition that can be found in contrastive instances from the corpus. In rhetorical structure theory, Azar (1997, p. 305) states that, by employing antithesis, “the reader’s positive regard for the nucleus is increased by his/her comprehension of the satellite and the incompatibility between the situations presented in the nucleus and in the satellite”. Following on from this definition, Green (2022: p. 9) adds that one cannot have positive regard for both the situations which are presented in the nucleus (N) and the satellite (S). Hence, if the position described in S has negative regard, the reader will have positive regard for the situation described in N:

- [Annuals die each year and must be replanted] S

- [Perennials can stay green year-round…] N

Antithesis has also been studied as a rhetorical figure, defined as “a verbal structure that places contrasted or opposed terms in parallel or balanced cola or phrases. Parallel phrasing without opposed terms does not produce an antithesis, nor do opposed terms alone without strategic positioning in symmetrical phrasing” (Fahnestock, 1999, pp. 46-47). Fahnestock (1999, p. 48; 2011, p. 232) expands this definition by introducing several types of oppositions as developed by classical rhetoricians and semanticists:

For Fahnestock, a perfect antithesis entails the use of pairs of terms opposed by means of contraries, contradictories, or correlatives which occur in parallel phrases.

III. CORPUS METHODOLOGY

The data for this research have been obtained from COWITE19. The sub-corpus includes texts written by women as instructions to guide the reader throughout the preparation of a recipe. The cognitive domain largely represents the field of cooking and all its culinary names concerning the array of ingredients and types of dishes selected in each book. However, COWITE19 also contains recipes about medical and pharmaceutical remedies, among others.

The version employed for this study comprises texts collected up to 15 January 2023, which belong to the recipe genre and reflect an expositive text-type. The texts derive from both printed and manuscript sources located in UK and USA libraries and have been computerised and stored as plain text which can be used in linguistic software for its consultation and retrieval.

The collection of recipes fulfils several criteria alongside the required expositive and instructive nature of the texts. For example, the authors must be women who were native speakers of British or American English. The texts have to be taken from the earliest available edition, provided that the authors were alive in the nineteenth century. Likewise, the books could not be new editions or copies of material already published in the previous century or earlier. A further condition requires that the compilations need to cover material from each decade from 1800 to 1899, and are of a similar size or contain a similar word count. Hence, about 50,000 words have been collected per decade. The number of words must be obtained from more than one source; moreover, the texts that belong to more than one volume must be carefully chosen to ensure that the manuscripts do not have similar or repeated content which could alter representativeness. For this study, I have selected the books published between 1806 and 1849. Table 1 shows the distribution of COWITE19 during this period into files, tokens, types, and lemmas:

Table 1. Number of files, tokens, types, and lemmas of COWITE19 during the period 1800-1849..

| Files | Tokens | Types | Lemmas |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 222256 | 7591 | 7199 |

The list of contrastive markers found and analysed in the corpus are the following:

- Adverbs: “nevertheless”, “however”, “yet”.

- Coordinating conjunction: “but”.

- Subordinating conjunctions: “although”, “though”, “even if”, “whereas”.

As to the methodology employed for this study, the corpus was interrogated to find examples of the contrastive markers shown above by making use of the software CasualConc developed by Yasu by Imao. The findings were then copied to an Excel spreadsheet incorporating a context of 40 words on both sides of the markers in order to identify and categorise each instance properly, as reflected in section IV.

IV. RESULTS OF THE CORPUS STUDY

As can be observed in Table 2, the coordinating conjunction “but” is the most employed marker, with 501 cases and varied interpretations, as will be discussed below. The incidences of other contrastive linkers are much less numerous. “Though” and “however” appear 14 and 10 times respectively and the type of semantic opposition found is D-concessive. “Yet” is examined only in six sentences with the same D-concessive explanation, and “whereas” occurs in three sentences, one of them with a contrast reading and two with a D-concessive one. “Nevertheless”, “even if” and “although” only appear once in the corpus with a D-concessive meaning.

Table 2. Distribution of contrastive markers in the corpus..

| Marker | Number of occurences |

|---|---|

| But | 501 |

| Though | 14 |

| However | 10 |

| Yet | 6 |

| Whereas | 3 |

| Nevertheless | 1 |

| Even if | 1 |

| Although | 1 |

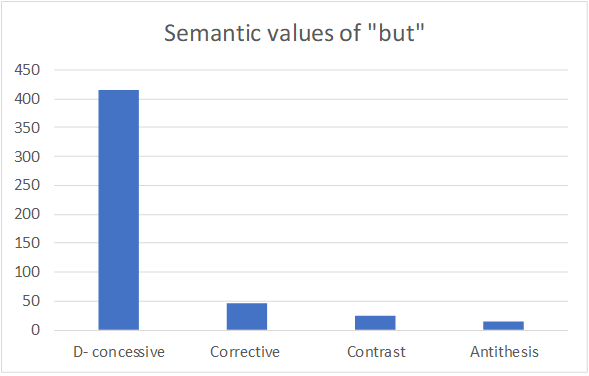

With respect to the results of Figure 1, the D-concessive meaning of “but” is the most numerous, with 416 cases, followed by the corrective opposition with 46 examples, the contrast interpretation with 25 occurrences and, finally, the antithesis relation, with 14 instances. Each type of semantic opposition relation is illustrated with several excerpts in the subsections below.

Figure 1. Distribution of semantic values of “but”.

IV.1. Contrast relations

Most contrastive occurrences in the corpus do not compare different entities, but different aspects of one entity, such as the age, the size or the weight of the product being cooked. The contrast is valid in that the CIs are explicitly indicated, and the presence of a shared domain characterises the contrast (Izutsu, 2008, p. 659). Example (11), however, includes two groups of CIs which represent different entities: “mutton” and “beef” in the first sentence and “veal”, “pork” and “lamb” in the second. Within the general domain of “cooking”, the mutual exclusiveness entails the degree of boiling that both types of animals require to be nutritious.

In (12), a ham is being contrasted by its age, “a green ham” vs. “an old ham”, so we can judge the CIs as two different tokens of the same identical entity, that is, “a ham”. The shared domain is that of cooking, and the mutual exclusiveness opposes “no soaking” to “must be soaked sixteen hours in a huge tub of water”. In this case, the contrast is acceptable because the difference between CIs is clearly indicated by the adjectives regarding the age. In (13), likewise, the CIs contrasted affect the size of “a pig” and the time needed for roasting it, in case the animal is “a fine young pig” or “a large one”. The weight of the entity “beef” entails the next compared feature in (14), being the shared domain that of “roasting”. Finally, example (15) does not focus on the cooking of meat but of vegetables. On this occasion, both the age and size of the entity “carrots” is considered in its boiling time. The CIs are further distinguished by two names: “spring carrots” vs. “Sandwich carrot”.

IV.2. Concessive relations: D-concessive

The most recurring semantic opposition found in the corpus is concession, in particular, the D-concessive type, mainly expressed by means of “but”.

In the cognitive domain of cooking that is being considered, these concessive sentences usually fulfil a non-argumentative role in that they describe a state of affairs aimed at defining the necessary steps in the art of cookery; that is, they detail the procedure needed to prepare a dish. The concessive segments are thus meant to describe states of affairs and to increase interest by adding apparent contradictory information (Azar, 1997, p. 308), or by conducting “opposition relations that bind the spans of two texts, one denying the expectations arisen from the other one” (Musi, 2018, pp. 270). From a rhetorical argumentation perspective, however, concessions can convey the idea that the speaker offers a favourable reception to some of the hearer’s real or presumed arguments with the aim of strengthening his position and making it easy to defend (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969, p. 488). Along the same lines, Azar (1997, pp. 308-309) argues that direct concessions can contain an argumentative relation because the speaker aims to make his/her primary idea more acceptable to the reader. Indeed, in elaborating the collection of recipes, the writer wishes to advise the prospective cook not to take certain wrong steps which could spoil the food. In that case, the author employs a persuader, that is, “a psychologically manipulative technique” which is reflected in the concession as a type of weaker argument. The use of a persuader is meant for increasing or changing belief or approval and for guiding the recipient towards the expected goal; likewise, it becomes a source of advice and recommendations during the elaboration of the recipe. Nevertheless, the relation of direct concessive in the corpus can be interpreted as argumentative, in so far as the writer wishes to initiate and advise the future cook to follow her guidelines. Presumably, not following these instructions could potentially ruin the desired dish.

Crevels (2000, pp. 316-320) establishes up to six entity types that classify the semantic types of concessive clauses. In our corpus, we highlight the occurrence of three of those entity types: the state of affairs, the text unit, and the speech act, each one illustrated in the next three examples (Crevels, 2000, p. 317; Musi, 2018, p. 275):

In (16), the occurrence of “although” does not impede the accomplishment of the event reflected in the main clause. This concessive construction entails “a real world or content relationship” (Crevels, 2000, p. 317) because the rain, presented as an obstacle, does not prevent us from going for a walk. As to (17), the concessive clause that contains “although” extends over a sequence of preceding utterances indicating an unanticipated turn in the context, namely, the speaker realises that he/she has expressed his/her true feelings in all the languages he/she speaks and writes, not only in Romani. Finally, in (18), the concessive clause entails an obstacle to the speech act expressed in the main clause. As will be seen below, the directive speech act is significant in the corpus whenever the writer gives a series of commands to the reader during the description of the recipe.

As explained above by Izutsu, the compared items (CIs) of the concessive relation are usually two different tokens of the same entity, as in the following examples:

The D-concessive reflects an implication that the relation between the situations of the clauses above is unexpected as to the outcome of events assumed by the speaker. The assumption that is naturally thought of is the following: “If S1, (then normally) not S2”. In (19), the fact that “moist sugar may be clarified in the same way” as candy sugar may make us assume that there exists only that way of preparation; however, “it requires longer boiling and scumming” than candy sugar, so both types of boiling process can be seen as mutually exclusive regions in the shared domain of, we could say, “cooking sugar”. In addition, two different CIs are two different tokens of the identical entity, that is, the reference to “moist sugar” in the first clause and “it” referring to that same kind of sugar in the second clause. This type of concessive, which involves an assumption evoked from the propositional content of the first clause, is the most frequent in the corpus selected. In (20), the CIs regard the different styles of cooking a shoulder boned to make venison pasty. It is not enough a piece of this meat for its preparation since it requires the inclusion of other ingredients that the reader does not possibly expect. The explanation of the second clause implies an assumption also derived from the first one. Example (21) includes the marker “though”, fulfiling the same function as “but” in the instances above. The CIs are two different tokens of the same entity, “liquor”, and occupy mutually exclusive regions in the shared domain of “boiling liquor”. As before, the second clause shows a detailed instruction as to the intensity of the liquor that the reader is not likely to know about. Finally, (22) displays the only example of “even if” in the corpus selected. The CIs refer to the different occasions when someone can eat cod provided that it is conveniently salted. The propositional content of the first clause asserts the ideal way of eating cod, a fish that is generally salted in the preparation of a number of dishes and that usually requires a certain period of time to be properly consumed. This assumption, evoked from the first segment of the sentence, is relevant to the interpretation of the subordinate clause, which suggests that the cod can be equally tasty “even if to be eaten the same day”.

However, in other instances from the corpus, the CIs are two different tokens belonging to different entities, as in (23), which shows a D-concessive pattern containing the only occurrence of “nevertheless”. The propositional content of the first clause seems to evoke the assumption that, since brewing is not likely to be a feminine occupation, women should not be skilful in this art. In (24), similarly, the assumption suggests applying whiskey to alleviate a skin disease although the writer admits to not knowing about this remedy. The concessive marker of this last occurrence links a text unit entity type because the author has previously enumerated several ailments and their possible treatment. This extract also contains another “but” concessive structure which connects two different tokens of the entity “healing”.

In (25), the implied subject of both imperatives is “you”, so the CIs are two tokens of the entity regarding the recipient of the recipe. There is no mutually exclusive relation between the actions of taking off “a bit of the meat for the balls”, letting “the other be eaten” and “simmering” the bones in the broth, but they can be interpreted as complementary activities in the cooking process that contribute to the guiding tone of the instruction. In (26), the CIs are two different tokens belonging to different entities, that is, “some people”, and “you” as implied subject of the imperative “cut off”. Alongside the concessive clause, the author introduces a causal segment that justifies why to “cut off the ears at the roots” to a hare. Finally, in (27), the procedure for boiling a cabbage contains a list of several imperatives both in the first and second clauses. Again, the implied subject of both imperatives is “you”. In the case of the concessive segment, it is supported by a conditional clause that helps to elucidate why the reader must not squeeze the boiled leaves of that vegetable.

IV.3. Corrective

I have picked up three examples of corrective opposition which display several verbal and nominal forms, all of them entailing a direct rejection of the previous segment:

In (28), the negative adverb “seldom” announces to the reader that “a pig” is not usually “sent whole to the table” in the first segment (S1), anticipating the alternative present in the second one (S2), which offers a detailed explanation of how the pig is dressed by the cook. A past participle is the verbal form employed in both segments to signal the two (CIs), “sent (whole)” vs. “cut up”, of the entity “pig”; in (29), nevertheless, the same demonstrative pronoun, “those”, is repeated in the two segments to refer to the entity “meat”. The corrective relation is introduced as part of the writer’s advice to save money when shopping for cheap pieces of meat, and specifies the importance of not only the price of that food, but also the good use given to it. Finally, in (30), the corrective sentence regards the phases in the process of brewing beer, in which the author indicates, by means of two present participles, how to treat “the scum” of the liquid, not taking it off, “but stirring it down”.

IV.4. Antithesis

This part of the analysis examines the occurrence of antithesis in contrast sentences. Cases have been isolated where there is a semantic opposition which appears in parallel structures, and which can be categorised according to Fahnestock’s classification:

In (31), for instance, we can observe two pairs of contraries between “male” vs. “females” and “soft” vs. “hard”. It can be interpreted as a contrastive sentence in that the CIs entail two different aspects of one entity, that is, “roe of a male fish” and “[roe] of the female”. The consistency of the roe into “soft” and “hard” is also opposed alongside the sex by means of parallel copulative sentences. Example (32), similarly, contrasts two different aspects of the entity “salts”, and both the subject and predicate reflect parallel structures. Whereas “medicinal” and “poisonous” can be interpreted as contrary adjectives, especially in a healing or curative domain such as this one, the adjectives found in the predicates just qualify the noun “taste”, which is also repeated. The resulting pairing provides a rhythmical sequence of opposite meanings. Example (33) regards the possible value of the entity “bottles” in accordance with the material of which they are made. The mutually exclusive relation is found between the material of both bottles: those made of “good thick glass” are worthy and those of “French thin glass” are worthless. The parallelism derives from the use of two symmetrical conditional sentences and the contraries “thick” and “thin”.

V. CONCLUSIONS

This study has analysed the use of contrastive markers from COWITE19 samples throughout the period which spans from 1806 to 1849. The inclusion of these opposing devices is justified throughout the instruction process involved in the development of a recipe, from the preparation and cooking time to the selection of ingredients and the steps needed in the elaboration of the dish. Following Izutsu’s model of analysis for semantic opposition relations, three main types of relations have been identified which establish contrast, concessive and corrective meanings, as well as antithesis as a rhetorical figure.

The most repeated discourse marker is the coordinating conjunction “but”, employed in all the opposition relations examined. In the contrast relation, the mutual exclusiveness of different compared items (CIs) comprises different aspects of one entity in a shared domain, rather than two different CIs. As it is usual, this contrast aims at elucidating distinct elements which help the reader during a certain phase of the cooking process. Within the concessive relation, the D-concessive is by far the most recurrent. In this kind of concessive sentence, the mutual exclusiveness is established between the propositional content of the second clause and an assumption evoked from the first clause. Although D-concessive sentences are usually non-argumentative, an argumentative relation or persuader has been favoured, in that the writers of recipes seek to advise and guide the reader towards a successful accomplishment of the dish. This argumentative value is reinforced by the use of imperatives in one or both clauses, functioning as commands and having the illocutionary force of directives. The corrective relation is also found in the corpus as a further way of rejecting one element of the recipe and relocating an alternative, thus presenting a more detailed direction to the future cook. Finally, reference has also been made to antithesis as an opposing structure, that not only compares the clauses by means of a linker but also involves the lexical repetition of words, phrases or even clauses. The possible argumentative value of this rhetorical figure derives from the parallel phrasing that favours a better understanding of the opposition.

VI. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research conducted in this article has been supported by the Plan Estatal de Investigación Científica, Técnica y de Innovación 2021-2023 of the Ministerios de Ciencia e Innovación under award number PID2021-125928NB-I00, and the Agencia Canaria de investigación, innovación y sociedad de la información under award number CEI2020-09. We hereby express our thanks.

VII. REFERENCES

Abraham, W. (1979). But. Studia Linguistica, 33(2), 89-119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9582.1979.tb00678.x

Alonso-Almeida, F., & Álvarez-Gil, F. J. (2020). ‘So that it may reach to the jugular’. Modal verbs in early modern English recipes. Studia Neofilologiczne, 16, 61-88. https://doi.org/10.16926/sn.2020.16.04

Alonso-Almeida, F., Ortega-Barrera, I., Álvarez-Gil, F., Quintana-Toledo, E., & Sánchez-Cuervo, M. (Eds.) (2023). COWITE19= Corpus of Women’s Instructive Writing, 1800-1899. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. Anscombre, J. C., & Ducrot, O. (1977). Deux mais en français? Lingua, 43(1), 23-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3841(77)90046-8

Azar, M. (1997). Concessive relations as argumentation. Text, 17(3), 301-316. https://doi.org/10.1515/text.1.1997.17.3.301

Biber, D. (1988). Variation across speech and writing. Cambridge University Press. Blakemore, D. (1987). Semantic constraints on relevance. Blackwell. Blakemore, D. (1989). Denial and contrast: A relevance theoretic analysis of ‘but’. Linguistics and Philosophy, 12(1), 15-37. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00627397

Crevels, M. (2000). Concessive on different semantic levels: A typological perspective. In E. Couper-Kuhlen & B. Kortmann (Eds.), Cause. Condition. Concession. Contrast. Cognitive and Discourse Perspectives (pp. 313-339). Mouton de Gruyter. Dacal, M., & Katriel, T. (1977). Between semantics and pragmatics: The two types of ‘but’ – Hebrew ‘Aval’ and ‘Ela’. https://doi.org/10.1515/thli.1977.4.1-3.143

Fahnestock, J. (1999). Rhetorical figures in science. Oxford University Press. Fahnestock, J. (2011). Rhetorical style. The uses of language in persuasion. Oxford University Press. Foolen, A. (1991). Polyfunctionality and the semantics of adversative conjunctions. Multilingua, 10 (1/2), 79-92. Green, N. L. (2022). The use of antithesis and other contrastive relations in argumentation. Argument & Computation, 14(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.3233/AAC-210025

Greenbaum, S., & Quirk, R. (1990). A student’s grammar of the English language. Longman. Halliday, M. A. K. (1994). Edward Arnold. Imao, Y. (2022). CasualConc (Version 3.0). [Computer software]. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/site/casualconcj/

Izutsu, M. N. (2008). Contrast, concessive and corrective: towards a comprehensive study of opposition relations. Journal of Pragmatics, 40(4), 646-675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2007.07.001

Kehler, A. (2002). Coherence, reference, and the theory of grammar. CSLI Publications. Lang, E. (1984). The Semantics of coordination. John Benjamins. Langacker, R. W. (1987). Foundations of cognitive grammar (Vol. 1). Theoretical prerequisites. Stanford University Press. Langacker, R. W. (1991). Foundations of cognitive grammar (Vol. 2). Descriptive application. Stanford University Press. Lyons, J. (1971). Semantics (Vol. 2). Cambridge University Press. Martin, J. R. (1984). Language, genre, and register. In F. Christie. (Ed.). Children writing: A reader (pp. 21-29). Deakin University Press. Musi, E. (2018). ‘How did you change my view?’ A corpus-based study of concessions’ argumentative role. Discourse Studies, 20(2), 270-288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445617734955

Perelman, C., Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). In J. Wilkinson & P. Weaver Trans., The new rhetoric. A treatise on argumentation. University of Notre Dame Press. Rudolph, E. (1996). Contrast: Adversative and concessive expressions on sentence and text level. Walter de Gruyter. Spooren, W. (1989). Some aspects of the form and interpretation of global contrastive coherence Relations [Doctoral dissertation, Nijmegen University]. Sweetser, E. E. (1990). From etymology to pragmatics. Cambridge University Press.

Takahashi, H. (2008). Imperatives in concessive clauses: Compatibility between constructions. Constructions, 2, 1-39. https://doi.org/10.24338/cons-454

Thompson, S. A., Longacre, R. E., & Hwang, S. J. J. (2007). Adverbial clauses. In T. Shopen (Ed.), Language Typology and Syntactic Description. Volume II: Complex Constructions (pp. 237-269). Cambridge University Press. von Klopp, A. (1994). But and negation. Nordic Journal of Linguistics, 17(1), 1-34. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0332586500000032

Winter, Y., & Rimon, M. (1994). Contrast and implication in natural language. Journal of Semantics, 11, 365-406. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/11.4.36

Received: 01 March 2023 Accepted: 14 April 2023