Do top-down and bottom-up agents agree on internationalisation? A mixed methods study of Spanish universities

University of Zaragoza, Spain

ABSTRACT

This paper explores the implementation of internationalisation in the Spanish university system and its effects from a mixed methods approach, combining quantitative corpus linguistics techniques and qualitative interview protocols. Results showed that Spanish universities’ written policies align with the national framework and rely on a complementary use of ‘abroad’ and ‘at home’ orientations for research and education. The main internationalisation strategies identified are mobility, collaboration, and English-medium instruction. A positive representation of internationalisation is also identified, with both top-down and bottom-up actors stressing its benefits for individuals and society. Yet, some critical voices pointed at mismatches between institutional views and stakeholders’ experiences, questioning the sufficient allocation of resources and lack of recognition and incentives. The paper argues that effective comprehensive internationalisation should include written internationalisation plans, communication strategies, and a clearly defined internationalisation models adapted to the universities’ particularities.

Keywords: Internationalisation, Spanish higher education, collocate analysis, document analysis, semi-structured interviews.

I. INTRODUCTION

In the last decades, globalisation has become one of the main drivers for the modernisation of higher education. As a response to the needs and demands of a global society, universities worldwide have developed internationalisation strategies (Altbach & Knight, 2007; Knight, 2004). Despite the wide range of definitions in the scholarly literature, there is a consensus about internationalisation consisting of at least the introduction of an international, intercultural, or global dimension into the university’s functions of research, teaching and administration (de Wit et al., 2015; Knight, 2004).

To illustrate the relevance of internationalisation in the European context, the European Commission has designed several policy documents to provide the member states with a space for cooperation, mobility, and intercultural awareness to “build a competitive and world-class European Higher Education system” (Evans, 2006, p. 41). Many of these European strategies (2013, 2019) address, among other things, the acquisition of transversal competences such as communication skills, global citizenship skills, professional skills, interpersonal and personal skills, and ICT skills, which are crucial for the labour market (Jones, 2013, 2020; Murray, 2016; Spencer-Oatey & Dauber, 2015). More specifically, the European Commission (2013) is focused on developing comprehensive internationalisation, which consists of three main transversal areas: “international student and staff mobility; the internationalisation and improvement of curricula and digital learning; and strategic cooperation, partnerships and capacity building” (p. 4). Hence, these policies stress the relevant role played by internationalised universities, which are essential to thrive in an interconnected and globalised world (European Commission, 2019; Sursock & Smidt 2010).

There is a clear-cut distinction between the strategies focused on ‘exporting’ and those focused on ‘importing’ internationalisation. Traditionally, internationalisation tended to understand export-oriented initiatives (internationalisation abroad) as the main indicators of internationalisation such as mobility-related strategies, cross-border educational programmes, recruitment of international students, international collaboration between researchers and institutions, and the delivery of cross-border education in off-shore campuses or joint degrees (Maringe & Foskett, 2010; de Wit, 2011; de Wit et al., 2015; Sursock & Smidt, 2010; Teichler, 2009). Internationalisation at home (import-oriented), by contrast, pays more attention to language learning, multicultural issues, curriculum development and transversal skills acquisition for those students and staff who stay on the local campus and do not engage in physical mobility. In doing so, these initiatives contribute to the achievement of internationalised learning outcomes, global competence, and cultural diversity in the domestic campus (Beelen & Jones, 2015; Knight, 2012; Yemeni & Sagie, 2016).

Although internationalisation has been thoroughly studied from a variety of perspectives, previous studies in the Spanish context seemed to focus either on the internationalisation of one or few universities (Cardim & Luzón Benedicto, 2008; Rumbley, 2010; Soler-Carbonell & Gallego-Balsà, 2019; UNESCO, 2014) or on specific areas such as the connection between languages and internationalisation or student mobility and internationalisation rather than offering a transversal and comprehensive view of the state of internationalisation in the country (Doiz et al., 2013; Haug & Vilalta, 2011; Lasagabaster et al., 2013; Ramos-García & Pavón Vázquez, 2018).

To fill in this gap, this study aims at shedding light on the understanding of institutional internationalisation during the decade 2010-2020 from a holistic perspective as it comprises data from a representative number of Spanish universities’ internationalisation written policies combined with interview data from stakeholders. Due to the mixed methods nature of this study, internationalisation policies are textually analysed to determine their effect on institutional goals, implementation processes, and stakeholders’ experiences. In this way, supported by empirical data, it is more likely to identify potential mismatches between policy and the realities on the ground that could hinder internationalisation endeavours. The complementarity of data sources and methods was deemed necessary since, as Fabricius et al. (2017) claim, there seems to be a “significant difference between theory and internationalisation in practice” (p. 10). This paper addresses the following research questions:

1. What are the main goals and strategies included in Spanish internationalisation written policies?

2. To what extent do bottom-up agents’ internationalisation experiences align with institutional policies?

II. THE INTERNATIONALISATION OF SPANISH UNIVERSITIES

II.1. Top-down internationalisation policies

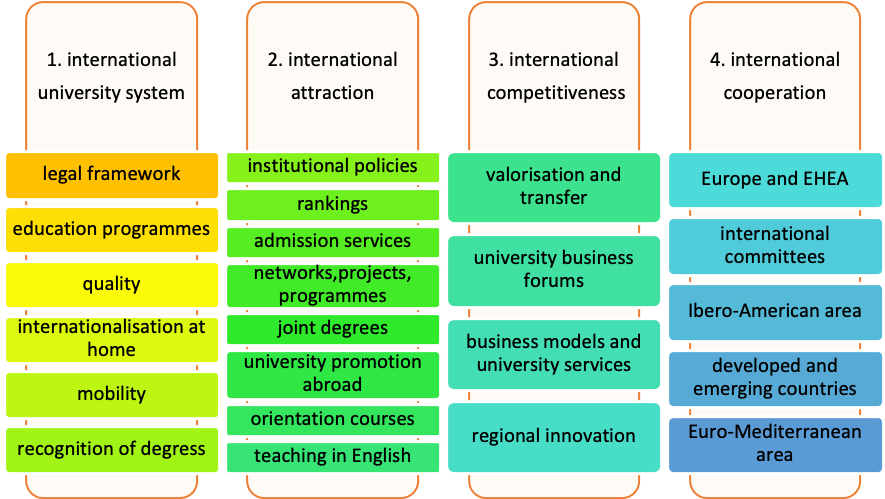

Since internationalisation has evolved from being considered a set of isolated activities to become a transversal goal embedded in the university’s mission, ethos, and values (Jones, 2020; Knight, 2004, 2012), the creation of a national strategy is advantageous for institutional policy development. The Spanish government launched the Strategy for the Internationalisation of Spanish Universities 2015-2020 (MECD, 2014) to provide universities with a general framework to succeed in a globally competitive society and to improve the Spanish university system’s quality and efficiency. Aware of the weaknesses of the university system such as the lack of internationalised study programmes, low rate of English competence, difficulties in the recruitment of international staff, or funding limitations, this strategy addresses the following objectives: the internationalisation of the university system, becoming internationally attractive, promoting the international competitive capacity of universities, and increasing cooperation with other countries (Figure 1). Each of the four objectives is complemented with specific actions that include resources, stakeholders, indicators, and timelines. In this way, the national strategy offers a roadmap to institutions that can be adapted to their context, needs and goals.

Figure 1. . General overview of the Spanish internationalisation strategy (adapted from MECD 2014)/span>

Within the second objective, boosting the international attractiveness of universities, it is mentioned the need to update institutional internationalisation policies, which aligns with the literature reporting the relevance of written policies by authors such as Childress (2010), Qiang (2003), Soliman et al. (2019), and Sursock and Smidt (2010). Their findings stress the relevance of written internationalisation plans because they include:

- well-articulated mission statements,

- clear and measurable goals,

- allocation of financial and human resources,

- stakeholder participation and active discussion of the plan,

- practical and achievable timelines and targets.

In the same line, Hénard et al. (2012) recommended a series of actions for effective comprehensive internationalisation based on the statement of clear objectives, adaptive strategies to the characteristics of the universities, the engagement of stakeholders along the process, and the introduction of quality assurance indicators. Thus, written plans are crucial as they become an essential tool for the implementation of internationalisation. In this way, universities show their commitment to internationalisation from a comprehensive point of view and provide guidance to stakeholders during the implementation, monitoring and dissemination of internationalisation endeavours.

II.2. Bottom-up internationalisation realities

Yet, to obtain a holistic view of internationalisation in the Spanish landscape, it should also be investigated from other perspectives to gain insights into the impact of internationalisation policies. In other words, to explore how internationalisation is understood not only from a top-down perspective through institutional documents but also from a bottom-up perspective investigating stakeholders’ perceptions towards internationalisation. The interrelation of both perspectives falls into the major strands of research in the internationalisation field identified by Bedenlier et al. (2018), which correspond to the combination of both institutional and bottom-up actors’ experiences and perceptions.

In this study, a group of scholars from a medium-sized Spanish university were considered one of the most suitable stakeholder groups because of their two-fold role in internationalisation at home and abroad strategies. Scholars are the intermediates between international students, bilingual education, research outputs, and international publication, which are activities highly valued by institutions to boost the international agenda and international visibility of universities. This stakeholder group, therefore, is deemed crucial for the identification of potential top-down and bottom-up mismatches. Likewise, it is a group highly influenced by institutional policies’ contents.

III.1. Corpus design and corpus-linguistic analytical techniques

A specialised corpus ad hoc was designed and compiled to investigate the nature and contents of the Spanish universities’ internationalisation policies. The corpus consisted of 66 internationalisation-related documents from 66 Spanish universities, which represent 79% of the Spanish university system (MECD, 2016, p. 5), bearing in mind issues of size, practicality, and representativeness (O’Keeffe & McCarthy, 2010). The documents were classified into internationalisation plans (n=22, 33%) and university strategic plans (n=44, 67%). When separate internationalisation plans did not exist, the university strategic plans were collected because they often included internationalisation-related information either as a strategic or transversal goal. Documents were downloaded from the universities’ websites, particularly from the international-related and transparency portal sections, and then saved in both pdf and plain text formats. Since the corpus compilation was carried out in 2020, the documents dated from 2012 to 2019, with most of them being published in 2015, probably as a consequence of the national strategy publication one year before.

AntConc v.3.5.7 (Anthony, 2018) was the software used to carry out a corpus linguistics-based study of the documents because it enables large-size corpora analysis to identify representative language use patterns (McEnery & Hardie, 2012; O’Keeffe & McCarthy, 2010). More specifically, a collocate analysis of the node internationalisation was carried out to identify the most-frequently associated words co-occurring with that term. The advanced search term ‘internationali*’ was employed to include all the multilingual occurrences of the term in Spanish, Catalan, Galician, and English. Lastly, a 5-span window (left and right) with a cut-off point of 4 and MI statistical measure were used to retrieve the data.

Once the result lists were gathered, an Excel spreadsheet was created to organise, clean, and analyse the data. Categories such as function words, university names, and proper nouns were deleted. The remaining 76 collocates of the node internationalisation were grouped together according to a corpus-driven taxonomy of semantic categories:

- Strategy refers to all the initiatives implemented for internationalisation goals in the different areas of university education.

- Agency includes all the stakeholders involved in internationalisation.

- Evaluation consists of nouns, adjectives and verbs including positive or negative discourse traits, as well as references to the own documents and internationalisation.

Each of these three categories comprises a series of collocates organised into subcategories, as can be seen in Table 1:

Table 1. Distribution of incoming and outgoing students

| Category | Subcategory | Collocates |

|---|---|---|

| Strategy | research teaching administration general |

research, development, innovation, knowledge, transfer programme, undergraduate, offer, teaching, formative, education, studies, PhD, postgraduate information, resources, website, support, service international, home, mobility, cooperation, culture, project, global, excellence, digital, employability, alliance, language, quality |

| Agency | source target |

university, vice-rectorate, institution, centres, office students, administrative staff, community, teaching staff, people, company, society |

| Evaluation | nouns adjectives verbs |

activity, objective, action, process, exe, indicatior, level, initiatives, line, field, factor, challenge, vision, plan, strategy, policy, document transversal, key, integral, opportunity, major increase, boost, foster, promote, drive, improve, bet, compromise, achieve, facilitate |

During the report of results, the collocates are written in italics because it is translated into English for the sake of grouping all the multilingual occurrences under one term. For example, the collocate university includes “universidad”, “universitat”, “universidade” and “university” and it is followed by its raw frequency in parenthesis e.g. university (n=84). Finally, the collocational results were complemented with a concordance analysis to guide the discussion of findings with real examples from the texts although the universities were anonymised. The excerpts employed in the discussion were translated into English for the same reason as the collocates.

III.2. Semi-structured interview and content analysis techniques

As part of a project focused on internationalisation and linguistic diversity in internationally engaged universities (cf. Vázquez et al., 2019), a series of semi-structured interviews were conducted with scholars from a medium-sized Spanish university to enquire about their attitudes and perspectives on internationalisation. Stemming from the question “what is an international campus?”, a protocol was designed to prompt answers and guide the follow-up conversation by asking other questions such as “what should your university do to be more international in research, teaching and management?”, “what are the most important actions that should be implemented to make your university more international?”, and “what are the main challenges for an international campus?” Also, some keywords were previously identified to assess the familiarity of the scholars with internationalisation such as mobility, exchanges, media, economic life, cultural value, global citizen vs. monolingual national citizen, teaching standards, linguistic landscapes, and second language instruction. The participants were approached following a snowball sampling technique that relies on the own interviewees to suggest potential colleagues for conducting more interviews once they had done it. A total of 26 scholars from the earth sciences (n=16, 62%) and social sciences (n=10, 38%) disciplinary fields were interviewed. The interviews were conducted in Spanish to facilitate comprehension and participation. They were recorded and manually transcribed, totalling 24,789 words.

The interview data were analysed with the software Atlas.ti v.8.4.2 that assisted the qualitative content analysis, which refers to “the systematic description of data through coding” to generate categories and analyse meaning (Schreier, 2014, p. 5). For doing so, an initial close reading of the transcriptions took place to familiarise with the interviews’ contents and then a first broad descriptive data-driven coding system was developed. After a second revision, an updated grouping and redefinition of the initial coding system allowed the accurate identification of key themes emerging from the interviews. Codes were grouped into three main themes (see Table 2) and each one included descriptive codes, e.g. specific characteristics of internationalised universities, and evaluative codes, e.g. approach (aspects to change), the importance of languages, or perceived weaknesses. During the qualitative analysis, a similar approach to other studies like Carciu and Muresan (2020) and Lourenco et al. (2020) was implemented.

Table 2. Main themes and codes emerging from the interviews.

| Themes | Codes |

|---|---|

| Strategies | mobility, collaboration, exchange, international projects, networks, research stays, teaching quality |

| Language dimension | English teaching, language courses, language support, website |

| Critical views | approach, bureaucracy, funding, institutional support, perceived weakness, recognition |

IV. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

IV.1. The main dimensions o finternationalisation policies

IV.1.1 Strategies

Among the numerous strategies found in the document corpus, the collocates indicating critical areas of action refer to research and teaching, which are considered key areas in the development of an internationalised and competitive university system.

Research (n=55) objectives are related to participation in international projects (n=12), associations (n=5) and networks that promote the visibility of research results through publications in high-impact journals. In fact, a current concern of universities is the applicability of the science they create; thus, research tends to be connected to ), development (n=15), ), innovation (n=13) and ), knowledge transfer (n=8) to society and companies, as found in institutional policies where research is framed as a crucial aspect of internationalisation. See for instance the following extract that summarises this view:

Since the beginning, research has been an international activity where work is carried out and disseminated through global mechanisms (international research projects and teams, exchange of ideas in international forums, publication in international journals, etc.). It implies that internationalisation is an indispensable requirement for research excellence. (Text 1, 2015)

The idea of cross-border collaboration for research purposes is shown with both the collocate international (n=55), which points to the scope of research, and the collocates mobility (n=24) and cooperation (n=14) to foster exchanges among different universities, research institutes, companies, society, and individuals. For instance, in the case of doctoral students, references to international research stays were found in the corpus to highlight the importance of international networking and collaboration from an early career stage.

The collocate home (n=24) is part of the phrase ‘internationalisation at home’ that focuses on the education dimension of universities as well as the allocation of resources to increase the universities’ international impact. The internationalisation at home approach focuses on the strategies and actions taking place at the local campus, and it seems that for Spanish policymakers, it takes the form of including an international dimension of teaching by means of using English-medium instruction. Likewise, the collocates in the sub-category teaching show that this approach appears in relation to undergraduate and graduate teaching programmes, particularly regarding language-taught courses and mobility programmes. Some of the specific strategies focusing on these two objectives can be summarised in the following extract, where the university designs a series of actions that range from creating international support measures on campus to promoting the university presence abroad with alliances (n=5):

Incentive programmes for bilingual teaching and international student mentoring. According to the internationalisation strategy of the [university], the mechanisms that promote the quantity and quality of English-taught courses must be strengthened. […] Promotion of joint and double degrees. The creation of international official double degrees and joint degrees within and outside the European Union is a line of action already started by the [university]. They comprise a competitive advantage for the enrolled students and an additional asset to the attraction of new students [...] (Text 3, 2020)

To succeed in the previous strategies, universities must offer their information (n=7) in different languages, as observed with the collocates accompanying the node such as the allocation of resources (n=7) to translate university websites (n=5) and other digital-related media (n=5) into English, as well as offering internationally related support (n=5) and service (n=5). In this way, an international audience may access the institutional information of research, teaching, management, and transference, aspects valued by international rankings and international quality agencies.

IV.1.2. Agency

As far as agency is concerned, the most salient collocate in this section is university (n=84). It appears both with a general meaning (institution, n=40) referring to the institution itself and with a specific meaning that identifies the different levels of university managers, represented by the collocates vice-rectorate (n=47) and centres (n=13). This finding is not surprising since the institution is the main responsible for creating these policy documents, so most references to this word refer to the university name as the primary agent promoting the mentioned strategies by means of explaining its objectives and positioning in favour of internationalisation. Their relevance is observed in their responsibility to create internationalisation plans, implement the contents described in those plans, and transform them into concrete actions.

Similarly, collocates such as activity (n=42), objective (n=37), action (n=36), are likely to precede detailed information about specific strategies for teaching and research and are followed by the expression “responsible agent: vice-rectorate of internationalisation/ international relations” once the action is mentioned.

Other identified actors refer to student s (n=19), administrative staff (n=14), teaching staff (n=11), and the university community (n=9), who are the main targeted groups by internationalisation plans. It is observed that these groups of stakeholders play a two-fold role in internationalisation. When actors are the ‘receivers’ of internationalisation strategies, it is observed how students are targeted with the majority of education and mobility strategies. In the case of the teaching staff, they are addressed with research-related strategies, mobility and incentives policies for foreign-language instruction. Lastly, the administrative staff receives language training actions.

On the other hand, when actors are responsible for ‘exporting’ internationalisation, the teaching staff includes an international dimension to their research activity, the administrative staff offers a quality service to international students and staff, and students can play an essential role as international representatives of their universities, as illustrated in the following extract:

Identification and dissemination of internationally prestigious alumni and researchers of the [university]. The university wants to create a network with members who belong or used to belong to the university community and who currently have an international curriculum of excellence. […] Increase the recruitment capacity of international teaching staff. […] Develop the actions related to the international mobility of students, teaching staff, and administrative staff (mobility, intercultural and language competences). (Text 1, 2015)

IV.1.3. Evaluation

Collocates included in the evaluation category such as the verbs increase (n=22), boost (n=18), foster (n=16), or promote (n=12) show the desire to spread the internationalisation endeavours all over the university context. Moreover, collocates like transversal (n=15), key (n=8) and integral (n=7) support the comprehensive approach to internationalisation that is embedded in all the university’s functions (European Commission, 2013; Knight, 2004, 2012). The occurrence of these collocates seems to confirm one more time the institutional commitment towards internationalisation and agree on the benefits it brings to society and the university community.

The positive representation of internationalisation in the analysed documents shows that in Spanish universities it is considered a strategic and transversal objective in the areas of research, education, and physical mobility. It is regarded as necessary to become internationally competitive and prestigious, aligning with the national and European supranational educational policies, and beneficial for society and the university community in terms of employment, collaboration, and skills acquisition essential requirements in modern society. The fact that institutional documents agree on the benefits of internationalisation connects with the ideas of Maringe and Foskett (2010), among others, who argue that top-down leadership and institutional support from agents specialised in internationalisation are essential factors for the effectiveness of such policies because a planned strategy provides stakeholders with opportunities to develop an international dimension. The primary tool that shows purposeful institutional commitment is embodied in written plans. They guide and overtly show the planning and implementation process of internationalisation to the university community.

IV.2. Bottom-up stakeholders' perceptions

IV.2.1 Strategies

Mobility and the exchange of people and knowledge between universities were identified as the main aspects of an internationalised campus. Outgoing mobility was considered to be well-established among the university community, yet, the incoming mobility of international staff and students was regarded as a challenge as a consequence of financial and legal restrictions for the recruitment of high-level international staff and recognition of hard work. For instance, the interviewees commented that the mobility programmes they participated in consisted of research stays motivated by their individual interests and the support provided by their research groups. Although they agreed on the high level of collaboration between different universities in international projects, their conceptualisation of a genuinely international university was based on their previous experiences working in Anglophone universities or central/Northern European research centres where multicultural research groups and international students were easily found.

In addition to collaboration for research purposes, exchange for teaching purposes emerged from the interviews. The following interviewee shares some interesting insights that envisioned a departmental exchange of people, materials, and resources to broaden their current teaching practices, by bringing innovation and quality to the education offered at the university:

No lo sé, pero a mi me gustaría que eso [internacionalización] fuera algo con profesores de otros países y que pudieras compartir asignaturas o en un departamento que hubiera gente de otras nacionalidades. Pero sobre todo que hubiera profesores, alumnos por supuesto, pero profesores también. Es que eso abriría muchos campos y un poco la mente de nuestros compañeros. (Translation: I don’t know, but I would like it [internationalisation] to be related to lecturers from other countries, that we could share subjects, or that in a department there were people from different nationalities. Particularly focusing on lecturers, for students too, but mostly for teachers. It would bring many possibilities for us, and it would turn some colleagues into more open-minded people) . (Respondent 7_earth sciences)

IV.2.2 Language dimension

Another emerging theme suggests the importance of sharing a lingua franca because it is essential for successful collaboration at different levels. For research purposes, English was identified as the international language of collaboration in international projects and publishing in international journals. The interviewees reflected on the importance of being competent in English since these were requirements for promotion and recruitment too. In the case of teaching and attracting international students, the presence of English-taught courses was considered a crucial initiative, as seen in the extract below:

La forma de ser atractivos es ofrecer cursos en inglés, que es lo que están haciendo la mayoría, que vamos ya retrasaos. Entonces hacer cursos en inglés, y también creo que entrar en contacto con universidades para dar y ofrecer programas conjuntos en inglés igual que esta la [universidad] con el MIT ofreciendo el máster. (Translation: The way to be attractive is by offering English-taught courses, something that most universities are doing, so we are already delayed. So, to offer English courses, but also to establish contacts with other universities to teach and offer joint degrees in English, similar to the collaboration between the [university’s name] and MIT). (Respondent 20_social sciences)

Alike the corpus findings about language-related strategies, interviewees agreed on the relevance of English not only for teaching and research but also for administrative purposes: a translated version of the website’s contents and information for students and researchers in English was essential for promoting the university's international profile.

IV.2.3 Critical views

Lastly, some critical views of the university’s internationalisation strategy emerged from the interviews. The first one referred to the weaknesses of the Spanish university system, which consisted of the lack of sufficient funding and the perceived lack of a clear purpose and scope for internationalisation. The participants agreed on the importance of internationalisation strategies and the benefits it brings to them as members of the community, however, they considered that the number of sacrifices they had to do to be part of it was too high because the institution did not grant enough support resources. Thus, scholars understand internationalisation as an enriching element for their careers and self-development, although they acknowledged the presence of potential challenges.

They also agreed on the mismatches between the university managers’ words and the current actions to implement the internationalisation plans in terms of restrictions and recruitment:

Para ser un campus internacional la [universidad] tendría que abrir su mente y dejar de ponernos limitaciones a los profesores, a los investigadores y proporcionarnos más medios para poder hacer intercambios y desde luego de alguna manera reconocer un poquito más el mérito de algunos investigadores que están haciendo buena investigación con muy pocos recursos y aquí en esta universidad no se les reconoce lo suficiente. (Translation: To be an international campus, the [university] should be more open-minded, stop putting limitations to lecturers and researchers, and offer more resources so that we can do exchanges. Also, it should definitely recognise the researchers’ efforts because they are conducting great research projects with little resources, and the university does not recognise their merit). (Respondent 6_earth sciences)

Tengo la sensación de que todos los dirigentes de la universidad, y no solo me refiero a los de más alto nivel si no incluso a nivel de centros, todos en sus programas cuando se presentan para dirigir una determinada facultad o instituto de investigación llevan la palabra internacionalización. Pero la mayor parte de los casos suele estar vacía. (Translation: I have the feeling that all university managers, from top to faculty management or research institute management, include internationalisation in their programmes. But most of the time it is just an empty word or catchphrase in most cases) . (Respondent 21_social sciences)

In other words, bottom-up agents called for a clarification of approaches to become a truly internationalised university, echoing the concerns raised by de Wit (2011) or Fabricius et al. (2017) about internationalisation being a mere buzzword. These comments lead to further reflection on the type of internationalisation that can and should be implemented at the university, its scope, capacity building, and the increase in the number of support resources offered by institutional agents. Some universities may prioritise specific areas if they have a research-oriented or teaching-oriented profile; if their internationalisation strategy specialises in some academic disciplines due to geographical or cultural characteristics or offers an equal transversal international dimension; if their goals of capacity building, attraction and retention are at the international or regional levels; just to mention a few examples (Bruque, 2020; Haug, 2020, 2021).

The interview data points to the relevant areas for Spanish internationalisation improving the quality standards of education and research, the participation of both academics and students, and the importance of clear institutional guidance that coincided with the key areas in the national strategy (MECD, 2014). These results also echoed the studies of Carciu and Muresan (2020) and Lourenco et al. (2020), whose findings reported that scholars associated internationalisation with the areas of mobility, quality, development of skills, and the use of English for knowledge transfer, research, and education. It is worth noting how the Spanish scholars’ perceptions of internationalisation shared similar features with Southern and Eastern European contexts. Despite the literature describing the dynamic nature of internationalisation, this shows how its core features are shared throughout different contexts, leading to comparability and replicability, particularly when the scholars’ definition of internationalisation is based on their individual international experiences rather than institutional policies.

The interviewees tended to look up to the Anglophone universities as the ideal models for an internationalised university according to quantitative indicators such as international students and international staff's presence. However, these should not be the only factors considered for an international campus, as recalled by Knight’s myths (2011). In her article, Knight warns about the importance of going beyond quantitative indicators to focus on the effectiveness and quality of an internationalisation plan because “quantify outcomes […] do not capture the human key intangible performances of students, faculty, researchers, and the community that bring significant benefits of internationalisation” (2011, p. 15). Hence, it is necessary to educate stakeholders on the impact of internationalisation through different initiatives in research, education, and service, involving the international and local communities. In-depth reflection points at aspects such as (soft) skills development of academics and students, development of language learning competence, integration of internationalised values and culture in the curriculum, or increasing innovation in teaching and research. These examples are thought to lead to an inclusive internationalisation of campuses from both bottom-up and top-down perspectives. Spreading internationalisation opportunities inside and outside the campus would activate reflection about the so-called internationalisation culture and acute understanding of the different internationalisation dimensions.

V. CONCLUSIONS

The analysis presented in this paper has aimed to compare data from written policies and interviews to study the implementation of internationalisation and identify its impact on Spanish universities’ stakeholders. Concerning the main goals and strategies of Spanish universities, there are similarities between the corpus findings and the four strategic objectives outlined in the national framework (MECD, 2014). Regarding the objective of creating an internationalised university system, all the strategies falling into the teaching dimension and mobility support this objective. Increasing the attractiveness of the university for international students and staff relied on language-based strategies, which was also identified as a challenging area for Spanish universities. The objective to become more internationally competitive focused mainly on research-based strategies promoting collaboration, visibility, and prestige. Lastly, cooperation goals were integrated into the previous strategies since many relied on mobility and networking. All in all, these findings show how institutions promote their international profile in research and teaching to increase incoming mobility and international capacity building, two weaknesses of the Spanish university system identified by the national strategy as well as the interview data.

The analysed strategies align with the comprehensive approach to internationalisation defined by the European Commission (2013) and Wit et al. (2015), where these initiatives are implemented in teaching, research, and management. Compared to the three key objectives outlined by the European Commission (2013), the objectives of mobility and strategic cooperation are thoroughly integrated and promoted in institutional policy. References to the creation of additional services and resources were mentioned in the interviews, which would certainly improve the international experiences of bottom-up stakeholders. In the case of the internationalisation of curricula and digital learning, universities opted for the introduction of English-medium instruction and joint degrees, ignoring other alternatives for the internationalisation of teaching. It could be suggested that policymakers could expand the range of at home strategies where the internationalisation of the curriculum includes a variety of initiatives promoting soft skills, digital competence, and the use of alternative teaching methodologies in addition to language learning and mobility (Beleen & Jones, 2015; Jones, 2013). In this way, internationalisation initiatives may be further elaborated to offer inclusive and integrating opportunities for all students, adapting to the needs of a globalised society (Jones, 2020; Murray, 2016; Spencer-Oatey & Dauber, 2015).

Despite the positive representation of internationalisation, it seems that Spanish universities find themselves at different stages of policy development, as seen during the corpus compilation and the level of familiarity of stakeholders with such policies. For instance, while it was frequent to find intertextual references to a wide range of top-down policies in the document analysis, the references to documents were almost non-existent during the interviews, which suggests mismatches between institutional policies and what information reaches bottom-up agents.

This study’s findings confirm that institutional policies go in the right direction in terms of implementation, in fact, many of the internationalisation strategies identified in the corpus align with the stakeholders’ perceptions of internationalisation (e.g. mobility, collaboration). Nevertheless, institutions need to go beyond quantitative indicators to meet bottom-up stakeholders’ needs. This is illustrated by the perceptions of some interviewees who concluded that their efforts were substantially more significant than the support and available resources they received from the university for teaching and research purposes. In this sense, efficient management, support services and funding are essential, as argued by Foskett (2010) and Iuspa (2010). Moreover, it is believed that the combination of recognition, incentives, and support plays an essential role in the stakeholders’ participation and satisfaction with internationalisation goals. Hence, an effective communication strategy is crucial for the dissemination of internationalisation initiatives among the university community to increase its impact, as suggested by the national strategy (MECD, 2014; see also European Commission, 2013; Hénard et al., 2012).

Another value of this study is observed in the methodological design, which combines both major trends in the field in the decade 2010s (Bedenlier et al., 2018; Yemeni & Sagie, 2016) by offering an in-depth reflection of the state of internationalisation in Spain. Despite the insights gained from this mixed methods analysis, a limitation of the study is the small interview sample. It would be recommended to expand the sample of the semi-structured interviews to other stakeholders in the institution such as students, other staff members, and policymakers; after all, internationalisation affects all the members of the university community. Similarly, another area for further research may focus on the replication of this study’s interview protocols in other institutions to get a bigger and richer overview of the Spanish university system and its stakeholders. The interviews were conducted in one university, so by increasing the scope of the interviews to more universities, the study would benefit from the diverse suggestions for policy design at the national level similar to the document analysis.

In the current era, when the local must think international, universities need to find the best solution to be both competitive and collaborative to thrive locally and internationally. Institutional policymakers, in collaboration with other stakeholder groups, should decide the most suitable model of internationalisation according to the context, strengths and weaknesses for international competition and collaboration to support the necessary measures, established or new, to reach institutional, national, and European objectives. In other words, universities should design strategies that stress the singularities of the Spanish universities, and adapt to their stakeholders’ needs to redefine collaboration, knowledge, and internationalisation in the next decade.

VI. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study is a contribution to the national research project FFI2015-68638-R MINECO/FEDER, EU, funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and the European Social Fund and to the research group H16_20R “Comunicación internacional y retos sociales” funded by the Regional Government of Aragon.

V. REFERENCES

Altbach, P.G., & Knight, J. (2007). The Internationalisation of Higher Education: Motivations and Realities. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(3), 290-305. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307303542

Anthony, L. (2018). AntConc (Version 3.5.7). Waseda University. https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software

Bedenlier, S., Kondakci, Y., & Zawacki-Richter, O. (2018). Two decades of research into the internationalization of higher education: Major themes in the Journal of studies in international education (1997-2016). Journal of Studies in International Education, 22(2), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315317710093

Beelen, J., & Jones, E. (2015). Redefining Internationalisation at Home. In A. Curaj, L. Matei, R. Pricopie, J. Salmi & P. Scott (Eds.), The European Higher Education Area: Between Critical Reflections and Future Policies (pp. 59-72). Springer.

Bruque, S. (2020). Hay que repensar lo global: ¿Un nuevo modelo de internacionalización? Jornadas Crue-Gerencias. 22nd October 2020, University of Zaragoza, Spain. Conference presentation.

Carciu, O.M., & Muresan, L.M. (2020). There Are So Many Dimensions of Internationalisation: Exploring Academics’ Views on Internationalisation in Higher Education. In A. Bocanegra-Valle (Ed.), Applied linguistics and knowledge transfer. Employability, internationalisation, and social challenges (pp. 203-222). Peter Lang.

Cardim, M., & Luzón Benedicto, J.L. (2008). Internacionalización de los estudios superiores: el caso de la Universidad de Barcelona. Universidad de Barcelona.

Childress, L.K. (2010). The Twenty-first Century University: Developing Faculty Engagement in Internationalization. Peter Lang.

Creswell, J.W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

de Wit, H. (2011). Globalisation and Internationalisation of Higher Education. Revista de Universidad y Sociedad Del Conocimiento, 8(2), 241-248.

de Wit, H., Hunter, F., Howard, L., & Egron-Polak, E. (2015). Internationalisation of Higher Education. European Union. https://doi.org/10.2861/444393

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford university press.

Doiz, A., Lasagabaster, D., & Sierra, J.M. (2014). What does ‘international university’ mean at a European bilingual university? The role of languages and culture. Language Awareness, 23(1-2), 172-186. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2013.863895

European Commission. (2013). European higher education in the world COM(2013) 499 final. Publications Office of the European Union. https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/1/2013/EN/1-2013-499EN-F1-1.pdf

European Commission. (2019). Key competences for lifelong learning. Publications Office of the European Union. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/297a33c8-a1f3-11e9-9d01-01aa75ed71a1

Evans, K. (2006). Going global with the locals: internationalisation activity at the University Colleges in British Columbia. [Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia]. https://doi.org/10.14288/1.0092937

Fabricius, A.H., Mortensen, J., & Haberland, H. (2017). The lure of internationalisation: paradoxical discourses of transnational student mobility, linguistic diversity and cross-cultural exchange. Higher Education, 73, 577–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9978-3

Foskett, N. (2010). Global markets, national challenges, local strategies: The strategic challenges of internationalisation. In F. Maringe & N. Foskett (Eds.), Globalization and Internationalization in Higher Education. Theoretical, strategic and management perspectives (pp. 35-50). Continuum.

Haug, G. (2020/07/14). “¿Internacionalización, «quo vadis» en la próxima década?” > https://www.universidadsi.es/internacionalizacion-universitaria-2020/

Haug, G. (2021, February 02). Prospectiva sobre la internacionzalización universitaria.< href="https://www.universidadsi.es/prospectiva-sobre-la-internacionalizacion-universitaria/">https://www.universidadsi.es/prospectiva-sobre-la-internacionalizacion-universitaria/

Haug, G., & Vilalta, J.M. (2011). La internacionalización de las universidades, una estrategia necesaria. Studia XXI.

Iuspa, F.E. (2010). Assessing the Effectiveness of the Internationalization Process in Higher Education Institutions: A Case Study of Florida International University. [Doctoral dissertation, Florida International University] http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/dissertations/AAI3447784/

Jones, E. (2013). Internationalisation and employability: The role of intercultural experiences in the development of transferable skills. Public Money and Management, 33(2), 95-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2013.763416

Jones, E. (2020). The role of languages in transformational internationalisation. In A. Bocanegra-Valle (Ed.), Applied linguistics and knowledge transfer. Employability, internationalisation, and social challenges (pp. 135-157). Peter Lang.

Knight, J. (2004). Internationalisation remodelled: definition, approaches, and rationales. Journal of Studies in International Education, 8(1), 5-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315303260832

Knight, J. (2011). Five Myths about Internationalization. International Higher Education, 62, 14-15. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2011.62.8532

Knight, J. (2012). Concepts, Rationales, and Interpretive Frameworks in the Internationalisation of Higher Education. In D.K. Deardoff, H. de Wi., J.D. Heyl & T. Adams (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of International Higher Education (pp. 27-42). SAGE Publications.

Lasagabaster, D., Cots, J.M., & Mancho-Barés, G. (2013). Teaching staff’s views about the internationalisation of higher education: The case of two bilingual communities in Spain. Multilingua, 32(6), 751-788. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2013-0036

Lourenco, M., Andrade, A.I., & Byram, M. (2020). Representations of internationalisation at a Portuguese higher education institution: From institutional discourse to stakeholders’ voices. Revista Lusófona de Educaçao, 47, 53-68. https://doi.org/10.24140/issn.1645-7250.rle47.04

Maringe, F., & Foskett, N. (Eds.) (2010). Globalisation and internationalisation in Higher Education: theoretical, strategic, and management perspectives. Continuum International Publishing.

McEnery, T., & Hardie, H. (2012). Corpus Linguistics: Method, Theory and Practice. Cambridge University Press.

MECD (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte). (2014). Estrategia para la Internacionalización de las Universidades Españolas 2015-2020. http://www.mecd.gob.es/educacion-mecd/dms/mecd/educacion-mecd/areas-educacion/universidades/politica-internacional/estrategia-internacionalizacion/EstrategiaInternacionalizaci-n-Final.pdf

MECD (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte). (2016). Datos y cifras del sistema universitario español. Curso 2015-2016. Secretaría General Técnica Subdirección General de Documentación y Publicaciones.

Murray, N. (2016). Standards of English in Higher Education: Issues, Challenges and Strategies. Cambridge University Press.

Hénard, F., Diamond, L., & Roseveare, D. (2012). Approaches to internationalisation and their implications for strategic management and institutional practice. A guide for higher education institutions. OECD Better policies for better lives.

O’Keeffe, A., & McCarthy, M. (Eds.) (2010). The Routledge Handbook of Corpus Linguistics. Routledge.

Qiang, Z. (2003). Internationalisation of Higher Education: towards a conceptual framework. Policy Futures in Education, 1(2), 248-270.

Ramos-García, A.M., & Pavón Vázquez, V. (2018). The Linguistic Internationalization of Higher Education: A Study on the Presence of Language Policies and Bilingual Studies in Spanish Universities. Porta Linguarum, Monográfico III, 31-46.

Rumbley, L.E. (2010). Internationalisation in the Universities of Spain: Changes and Challenges at Four Institutions. In F. Maringe & N. Foskett (Eds.), Globalization and Internationalization in Higher Education. Theoretical, strategic and management perspectives (pp. 207-224). Continuum.

Schreier, M. (2014). Qualitative content analysis. In U. Flick (Ed.), The Sage handbook of qualitative data analysis (pp. 170–183). SAGE.

Soler-Carbonell, J., & Gallego-Balsà, L. (2019). The sociolinguistics of higher education: Language policy and internationalisation in Catalonia. Palgrave Macmillan.

Soliman, S, Anchor, J., & Taylor, D. (2019). The international strategies of universities: deliberate or emergent? Studies in Higher Education, 44(8), 1412-1424. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1445985

Spencer-Oatey, H., & Dauber, D. (2015). How ‘internationalised’ is your university? Moving beyond structural indicators towards social integration. Going Global Event 2015.

Sursock, A., & Smidt, H. (2010). Trends 2010: A decade of change in European Higher. European University Association.

Teichler, U. (2009). Internationalisation of higher education: European experiences. Asia Pacific Education Review, 10(1), 93-106.

UNESCO. (2014). Informe sobre la internacionalización de las universidades de Madrid. Imprenta Gamar.

Vázquez, I., Luzón, M.J., & Pérez-Llantada, C. (2019). Linguistic diversity in a traditionally monolingual university: A multi-analytical approach. In J. Jenkins & A. Mauranen (Eds.), Linguistic diversity on the EMI campus. Insider accounts of the use of English and other languages in universities within Asia, Australasia, and Europe (pp. 74-95). Routledge.

Yemini, M., & Sagie, N. (2016). Research on internationalisation in higher education – exploratory analysis, Perspectives. Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 20(2-3), 90-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2015.1062057