EMI and the Teaching of Cultural Studies in Higher Education: A Study Case

Universidad de Sevilla, Spain

ABSTRACT

This paper examines students’ perspectives on the challenges raised by their first encounter with EMI pedagogy in higher education. The research was conducted with a group of beginner students with no previous experience in monolingual instruction in English. The case studied is based on two English Cultural Studies subject courses of the English Studies Program at a Spanish university and taught in a learning environment of total linguistic immersion. By activating their metacognitive and metalinguistic awareness, students were encouraged to take ownership of the stages of their learning process and assess it critically. Set at the intersection of EFL, ESP, and EAP, the specificities of these courses comprising linguistic and non-linguistic contents shed light on the teaching procedures employed in English Departments training programs, whose goals are to turn undergraduates into expert linguists and philologists and maximise their communicative proficiency in academic English.

Keywords: EMI; Cultural Studies; Higher Education; EFL; methodology

I. INTRODUCTION

This paper offers an overview of students’ appraisal of the problems they confronted with English as Medium of Instruction (henceforth EMI) for the learning of two English Cultural Studies courses in the context of the English Studies Program at Universidad de Sevilla. The methodology implemented to improve language proficiency at expert level and help them master disciplinary knowledge received a mixed response on the learners’ part, particularly during the initial stages. The results of the project identify Spanish newcomer students’ learning needs and the challenges perceived within the frame of EMI didactics. The courses selected for this study case are sequential, Estudios Culturales en Lengua Inglesa I and II; they cover core matters in the curriculum of the English Studies degree program and are mandatory for the first year of training. Both courses are fully English-taught, and deal with British and American cultural history contents. They offer trainees the necessary contextual background on different aspects of English-speaking nations’ cultural history and prepare them for the study of the specific English and American literature subject courses they will later take in the next three years to complete the program. The learning goals of this introduction to Cultural Studies are triple: on the one hand, to acquire the pertinent content-based disciplinary knowledge; secondly, to develop analytical skills to reflect on the construction of the discourses shaping the anglophone cultural tradition in different historical periods; lastly, to familiarize learners with the mechanics of academic writing in English. The classes are based on the analysis of a wide variety of key historical, legal, political, scientific and literary texts that have contributed to build and express the idiosyncratic aspects of the Anglo-American cultural heritage. This involves the upgrading of students’ hermeneutic skills, the employment of metacognitive strategies for the mastering of the categories of cultural analysis, as well as the increasing of linguistic proficiency.

All the class material (anthology of texts, class presentations, recommended bibliography, support documentation like charts, timelines, glossaries, questionnaires, tests, how-to guides, etc.) is provided in English. Likewise, all forms of instruction, explanations and learning procedures, as well as the in-class interaction with and among students are conducted in L2 in an integrative way. This way, EMI and Content and Language Integrated Learning (henceforth CLIL) teaching strategies are combined in order to create a learning environment of full immersion in academic English. Since the experience is set in the frame of the discipline of English Studies, the methodology puts to work the trainees’ metacognitive and metalinguistic awareness simultaneously, prompting them to fully engage with their education and to take responsibility for their own progression. In this sense, the course design was carefully planned to detect which EMI and CLIL resources were suitable to help first-year students adjust themselves better and faster to the higher education scenario. Further, it was essential for these beginner undergraduates to identify the possible gaps in their individual pre-college academic background so that they could receive specific guidance to bridge the deficiencies detected.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

EMI has become the object of systematic research in the context of Spanish higher education relatively late in comparison with neighboring nations. Until quite recently, Spanish tertiary education has been predominantly monolingual, except for those areas in which Basque, Catalan/Valencian and Galician are co-official languages at all educational levels. Until the last decade of the 20th c., there were no special plans for introducing English-taught courses in the university curricula beyond those of English for Specific Purposes (ESP), and most often these were initially restricted to the context of private universities. Usually, they focused on the areas of economics and business administration studies or on very specific branches of STEM and medical schools postgraduate programs. As a rule, the humanities and the arts came late to the incorporation of English courses to their curricula. In any case, the courses were mainly designed to prepare Spanish-speaking students for future career opportunities abroad rather than to attract international students to Spanish colleges. Besides, the presence of international faculty members and teaching staff was also scarce in all the levels of the Spanish educational system. In parallel to this, once it was clear that English had become the lingua franca for global communication and scientific research, universities started to offer optional courses in English for Academic Purposes (EAP). Habitually EAP classes were intended for faculty and doctoral candidates so that Spanish research could gain transnational visibility with publications in the most prestigious scientific journals. EAP training was only later introduced in undergraduate curricula.

In general, until very recently the language policy of Spanish universities did not pursue the internationalization agenda of other European countries’ tertiary education, which have for long resorted to EMI courses to widen their pools of prospective students. Even though the learning of English as a foreign language (EFL) has been mandatory in primary and secondary education in Spain since the 1980’s, and despite of the mixed success of the various bilingualism plans fostered by the regional governments, universities did not endorse bilingual undergraduate programs until 2002 (Dafouz & Nuñez, 2009). As of today, still many Spanish universities do not contemplate full instruction in English as a real possibility for all their degrees (Bazo et al., 2017).

In relation to this, we cannot forget the historical circumstances hindering the internationalization of Spanish tertiary education in the 20th century. The context of academic isolationism in the pre-democratic period caused that few foreign students considered joining Spanish universities before the 1960s, and those who did tended to be largely native Spanish speakers coming from Latin American countries, thus requiring no specific language policies to meet their formative needs. By the 1990s, however, the situation changed and progressively departments started to offer some English-taught courses in parallel to their regular Spanish-taught curricula. It is in the context of the application of the Bologna Process for the standardization of Higher Education in the European Union (EHEA) that since 1999 Spanish universities have been more consistent with the question of implementing EMI. To achieve the desirable balance of the subject content and language learning goals, lecturers resorted to CLIL methodologies, providing interesting insight on how to teach the many matters of scientific specialization in L2. In this vein, the stress fell first on producing tools and resources to teach English to a community of predominantly native Spanish-speaker students. Applied Linguistics and, in special, Functional Systemic Linguistics (SFL) approaches provided the main framework for the ensuing pedagogical investigation. With the application of the Common European Frame of References for Languages (CEFR) in 2011, EMI became central to assess Spanish universities’ chances to further their internationalization, so that they could take part in the competitive market of tertiary education. As a consequence, the methodological effort hitherto devoted to the teaching of EFL, ESP and EAP to Spanish speakers now concentrated on reconceptualizing EMI as the vehicular language to open the Spanish universities’ classrooms to the new international winds. Similarly, the implementation of EMI programs would attract more talented faculty members to their ranks.

Nevertheless, the problem at stake was that in order to integrate EMI into Spain’s higher education efficiently, it was necessary to start by addressing the challenges emerging from the low proficiency levels in English most Spanish undergraduates have when starting college. As stated above, the study of a foreign language is mandatory in the Spanish secondary education training curricula, with most students taking English as their first FL option (Eurydice, 2017). But experience shows that, unfortunately, despite the time and economic resources invested, Spanish average students can complete this stage without really reaching the desirable B1 level of proficiency marked by the legislation. The analysis of the reasons for the systemic failure of the teaching of EFL in secondary education, as well as the shortcomings of the equally flawed bilingual education programs, lie beyond the scope of this essay, but at the end of the day the deficiencies in pre-college training hinder their possibilities of success in EMI university programs.

One of the main issues is that, in general terms, students have had very few hours of exposure to real English, even though it has been proved it has a significant impact on any FL acquisition process (Muñoz, 2006). Likewise, we must also take into account that often the English class in high school is based on the explanation of grammatical and syntactical aspects, and that frequently this is conducted in Spanish or at least bilingually. In fact, learners rarely interact among themselves in English during the class sessions, limiting the use of the FL to the completion of language exercises. There is also a pronounced unbalance between input and output in English: the production of independent thinking-based oral and written pieces is very limited, and so for example, second-year baccalaureate students are not used to write compositions longer than one page, that is, just what they are required to do for the English language section of the university access exams. Since non-guided production, either oral or written, is not trained on a regular basis, it is not surprising that students’ fluency is underdeveloped, and this hurts their confidence to use English in out-of-school contexts. Additionally, although it is common for Spanish teenagers to take English classes as part of their extra-curricular activities, once again, they are trained to pass the official exams with the practice of standardized procedures. This enables them to answer language tests and produce very repetitive pieces of writing, but trainees are little encouraged to use English for communicating creatively. Thus, beginner students arrive at the university stage with a weak EFL background; those joining EMI and English-medium Education in Multilingual University Settings (EMEMUS) programs are prone to feel they are at disadvantage when comparing themselves both to their peer students following similar Spanish-taught programs and to international students, who are often equipped with more solid EFL/bilingual skills.

Another crucial factor at play is the absence or paucity of specific training for lecturers in charge of EMI courses in Spain (Muñoz, 2001; Aguilar & Rodríguez, 2012; Doiz, Lasagabaster, & Sierra, 2013; Fortanet-Gómez, 2013; Martín del Pozo, 2015; Jiménez-Muñoz, 2016; Dafouz & Camacho-Miñano, 2016; Sancho-Esper et al., 2016; Carrió-Pastor, 2020). Instructors are certainly fully competent in their area of scientific expertise and are normally required to certify a C1 level of proficiency in English; nevertheless, they are not always properly trained for teaching in English. Thus, they frequently lack the methodological qualification to use EMI efficiently, this being one of the main obstacles for faculty professional development.

In this context, the use of EMI within the academic area of English Studies is peculiar. To begin with, English Studies lecturers fulfill the requirements to teach in English as they are experts in language themselves and have received methodological training as well. In fact, English departments pioneered in the use of EMI; since the foundation of the academic area as Estudios de Filología Inglesa or Filología Anglogermánica in the late 1950’s, the language policy followed by English departments was that of implementing full instruction in the target language already in the earliest instances of the formative program. This marked a departure from the standard didactics of other modern languages/ modern philology departments (Santoyo & Guardia, 1982; Monterrey, 2003). Additionally, English faculty stressed the metalinguistic character of the training they offered, making undergraduates aware of the pedagogical strategies involved in the learning of the language-based and the non language-based contents. When considering the applicability of EMI in the frame of English Studies degrees, it is therefore important to have in mind Carrió-Pastor’s (2021) clarification:

CLIL and EMI approaches are similar in the sense that they are both forms of bilingual education but CLIL means teaching content through any foreign language while EMI means teaching content to students who are proficient in English (at least C1 proficiency level). Another difference is the perception of teachers’ role in both approaches. In both approaches, teachers know they are using a foreign language and thus they practice English while they teach content, but they differ in the aims of the class they deliver. On the one hand, in CLIL, teachers have a dual objective, that is, teaching both language and the subject content. On the other hand, in EMI, the content teachers do not think of themselves as language teachers; they only teach content speaking a foreign language (p.23).

In the practice, the courses taught by English Departments are at the intersection of these categories. For a start, lecturers are concerned with the teaching of specific contents on English Studies –linguistic and non-linguistic– at the very same time they must endow their students with the academic English skills necessary to access this knowledge. The non linguistics-based subject courses offered are intellectually challenging and encompass subjects matters like literature, history, art, science, economy, thus demanding the engagement of sophisticated cognitive procedures that should also find their expression in L2. Most frequently, beginner students realize that they do not possess the necessary communicative skills as yet. In fact, English Studies undergraduates’ achievement level of academic accomplishment is assessed on the two criteria of the assimilation of content-based knowledge, both linguistic and non-linguistic, and language correctness in the rendering of their newly acquired scientific expertise. From first-year students’ perspective, this is challenging, and their inexperience with EMI may bring about frustration and anxiety about the quality and future of their academic performance. The current research paper examines these issues and aims at offering some orientation to overcome the problems detected.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The study case presented analyses students’ perceptions on the difficulties faced in their first educational experience with EMI in two courses on Cultural Studies taught by the Department of English and American Literature of the Facultad de Filología at Universidad de Sevilla. The language policy in this study area establishes that all courses be fully taught in English during the four years of the training program; even for newcomer undergraduates, all forms of interaction with their instructor as well as students’ work is developed in L2 regardless of the shortcomings of the trainees’ performance during the first weeks of the school year. The learners’ production –class work, assignments, exams, tests, papers, projects, etc., both individual and collaborative— is to be submitted and revised in this language. It is then essential for beginner students to familiarize themselves with the EMI didactics as soon as possible so that they can meet the courses’ specific learning objectives. It is expected that, at the end of the academic term, they have acquired an advanced B2 level of English proficiency leading to the bilingual status they should reach throughout the next years. The close examination of the data collected in this research details first-years’ responses to these curricular requirements, and evidences their self-awareness on the developmental needs raised by EMI didactics.

The group of stakeholders selected took two sequential four-month courses, Estudios Culturales en Lengua Inglesa I (September-January) and Estudios Culturales en Lengua Inglesa II (February-June) in the 2020-2021 academic year, with a workload of 6 ECTS credits each one. The courses cover British and American cultural history contents and offer background knowledge in the field as well as training in textual analysis techniques and cultural critique. The students learn contents of a double nature: conceptual, consisting in the acquisition of fundamental background knowledge on the cultural history of English-speaking nations, and procedural, dealing with the interiorizing of the textual analysis skills necessary to identify and critically assess the discourses constructing this cultural tradition. Thus, Estudios Culturales I and II provide first-year undergraduates with the basis for the study of English and American literature subject courses they will take in the next three years leading to the obtention of their degree. Their understanding of the idiosyncratic traits of the culture of anglophone nations prepares them to develop future careers in the different contexts of intercultural communication too. The pedagogical approach adopted promotes students’ engagement and critical awareness, giving them the tools to describe and evaluate the discourses defining the Anglo-American cultural heritage. As Duraisingh (2021) points out, we cannot forget that “theories which seek to account for the increasing sophistication by which individuals make meaning of the world, such as the potential move from passively accept information from sources of authority to taking the responsibility of making meaning for oneself, embrace a constructivist as well as cognitive developmental stance” (p. 126). EMI didactics allow therefore to integrate the language and conceptual contents of these courses in an effective way. In the frame of this case study, the combined difficulty of working in a non-native language to make sense of its cultural milieu is perceived as doubly challenging by the trainees. It forces them to observe, contrast, compare and relate the native and the target cultural traditions, in whose languages – both in the literal and metaphorical senses of the term — they are conversant.

There are 4 hours of classes per week, and the sessions are designed to completely immerse students in an integrative learning environment that replicates the one they could have in any monolingual English-speaking academic institution. The methodological approach adopted is that of learning-by-doing and the pedagogy is student-centered, resorting to EMI and CLIL teaching strategies to enhance students’ analytical skills as well as to help them to develop their key linguistic competences in academic English. As Aguilar and Rodríguez put it, CLIL “plays a crucial role in acculturating university students into the language in which their discipline knowledge is embedded, constructed or evaluated” (2012, p. 184). The expertise learners acquire in the discipline of English Cultural Studies must be demonstrated by being able to carry out task-based activities in the form of textual analysis, group discussion of the topics proposed, and the elaboration of short critical essays (1500-2000 words) articulated as text commentaries. The learning objectives “are transformed into the ability to understand and produce literary texts thanks to the mastery of comprehension and production skills, which allow for the development of the ability to analyze works at a semantic and formal level as well as to carry out creative activities involving written production” (Ballester-Roca & Spaliviero, 2021, p. 230).

The study material comprises an anthology of texts, 31 for Estudios Culturales I and 28 for Estudios Culturales II. The selection was done by the teaching team of lecturers in charge of the courses, and the excerpts included illustrate the cultural history of English-speaking nations since the 1st century to present day. The texts chosen belong to different genres, ranging from historical chronicles to legal documents, pamphlets, speeches, poems, novels, plays, or film scripts, and all of them are presented in their original language version. Except for the Latin text on the Roman conquest of Britain, all the works were written by British or American authors, and are chronologically arranged from the 1st to the 21st century. The second type of study material provided to complement the text anthologies consists in the scientific bibliographical and reference material necessary for the study of each historical period, available through the University Library.

Working on English and American cultural contents in English turns out stressful for first-year undergraduates, specially during the earlier stages of the term. When the course starts, they are used to the teaching practices of secondary education, where classes were not completely English-taught and the material in English is often adapted, abridged, or has been especially created for the purpose of language teaching. As said above, higher education EMI courses are not focused on teaching the language, but in the case of English Studies boundaries are naturally much flexible and so the Estudios Culturales training program deliberately stimulates metalinguistic awareness is in order to facilitate first-year students’ introduction to the EMI model. To this end, some teaching strategies inspired on the CLIL toolkit (Doyle, 2010) are employed, in special those of scaffolding and sequencing. As the cognitive skills engaged must operate twofold in the scientific as well as in the linguistic field, it is relevant that the stages of learning be arranged gradually so that the less cognitively demanding tasks precede the more complex ones (Bloom et al., 1956). Helping first-year students to cope with the difficulties of combining the different thinking styles required is, then, crucial. As Álvarez-Gil (2021) highlights, in tertiary education contexts,

the ability to process the thinking about the learning process can motivate students that are frustrated because they are not able to acquire the adequate competences they need in order to evolve as well as bridge the gap some students have in their learning process since they can become aware of them and employ the appropriate tools to solve them (p. 324).

For this reason, Estudios Culturales learners receive constant orientation to solve both the content-related and language-related problems, especially at entrance level.

In this sense, English is always taught on practical, not theoretical bases. The different topics of cultural history are presented in class in English, and on the other, to ensure the complete understanding of the texts in the anthology illustrating these topics, their grammatical, syntactical and semantical complexities are carefully addressed during the lectures through close reading techniques. Likewise, glossaries and vocabulary lists are provided, and literary and cultural allusions clarified with the aid of reference material. Strictly speaking, these are not literature courses and the literary excerpts are studied as pieces of cultural history, yet the group receives basic information on the rhetorical and stylistic peculiarities of their artistic trends and period for those texts requiring it. Lessons are fully delivered in academic English, but the pace of explanations for new learners is slow: there is much repetition and glossing, written and visual support material is used to complement the oral input, students’ understanding is constantly checked, etc. The same philosophy applies to the monitoring of students’ textual production, both oral and written; they have practical class sessions in the form of writing workshops where they can have immediate feedback on errors, templates and style-sheets samples are supplied, etc. Similarly, a list of specific language aid on-line resources is published in the course digital platform. The study of the curricular matters of cultural history in English is facilitated with plenty of written and audiovisual materials like slideshow presentations on the syllabi topics, videos, audios, film clips, chronologies, royal genealogies, links to course-related digitalized manuscripts and historical documents, maps, and links to specialized websites for the study of British and American history, open access bibliographical repositories, as well as to sites of different libraries, museums and academic institutions’ resources where they could further investigate on the topics of their interest.

Students can always have individual consultation sessions with the lecturer so that they receive personalized feedback and supervision to solve the specific problems impeding their learning progression. Apart from this, they are strongly advised to make the most of the mandatory subject course of Lengua Inglesa I, taught by the English Language Department, whose contents are of a purely linguistic character.

III.1. Participants

Of the 46 and 40 students registered for Estudios Culturales I and Estudios Culturales II respectively, only 22 qualified as stakeholders for the purposes of this research. The selection criteria intervening were two: i) they took the two courses for the first time and therefore had no previous experience with EMI at higher education level, and none of them was a native speaker of English or bilingual; and ii) they took the courses with the same lecturer and they sat the final exams for both courses. These conditions were deemed necessary so that the impact of EMI methodology on them could be evaluated. It was also crucial that the participants’ increasing interiorization of the EMI class procedures could be monitored through the whole academic term, and so the informants’ learning progression was fully assessed by means of the summative and formative assessment of their academic performance. Even though the number of stakeholders for this research project may seem limited, we consider that the information presented is valuable and representative, as it replicates the beliefs former students shared with the lecturer in some more informal ways over the last years. It is also worth noting that the 2020-21 term was marked by the COVID-19 pandemic, and so the teaching modality has been hybrid, with onsite class rotations for one third of the students every two weeks whereas the other two thirds followed the session online via Blackboard Collaborate Ultra. Although these circumstances might have influenced some students’ attitude towards EMI pedagogy, the evidence gathered from the courses results and final grades presents no substantial variances with those of the past 5 years.

III.2. Method and instruments

Stakeholders were consulted only after they took the two courses in Estudios Culturales consecutively so that they could have a complete perspective on their exposure to EMI classes. Besides, the survey was conducted anonymously four weeks after the official publication of the final course grades of Estudios Culturales II so that students felt completely free to answer. The information was gathered from two sources: the first one was the online questionnaire with 14 items (22); the second source of data were informal personal interviews students had with the lecturer, in which the participants volunteered to comment on their experience with EMI training (6). These learners were inquired about their own perception of the challenges EMI classes posited for them in the first year of their college studies by being asked to score the level of difficulty of the different types of activities and tasks they performed for the courses. The scoring possibilities were easy, moderately complex, complex, and extremely complex. Students’ comments extracted from item fourteen in the questionnaire in answer to the question “what was the most challenging aspect of the courses for you?,” as well as the opinions expressed in the course of the interviews offer interesting insight for this study too; their words appear verbatim in the sections below, enclosed in quotation marks.

III.3. Data analysis

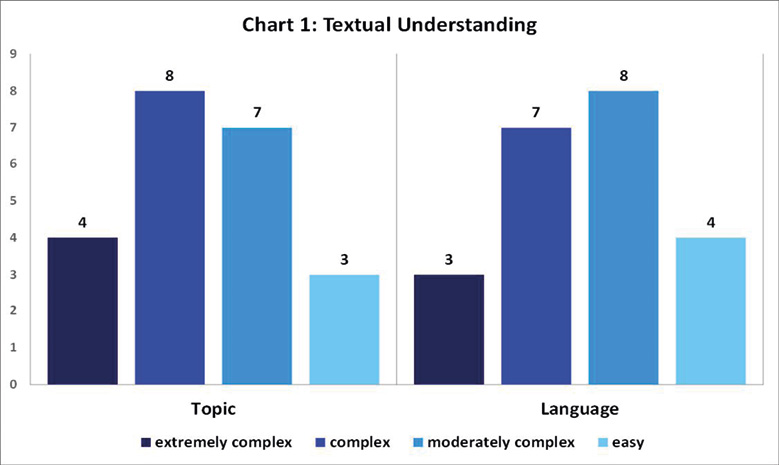

The first three items in the questionnaire dealt with the textual comprehension of the 59 excerpts included in the course anthology. Regarding their conceptual complexity, 14% stakeholders estimated that they could understand them easily; 32% said they had confronted some difficulty; 36% thought the task complex; and 18% found it extremely complex. This indicates that almost half of the group felt relatively confident with texts of an ample variety of genres –historical chronicles, essays, medieval romance, drama, novels, poems, film scripts, legal documents, manifestos and political speeches. For the rest of the group, the texts proved challenging mostly because they were not used to the genre conventions featured; the trainees claimed they had had no previous experience working with non-adapted texts in English other than short excerpts from narrative works, popular song lyrics, news reports, or advertisements in their secondary education textbooks. Very few participants had read literary works in their full English versions before. Some informants also pointed out at the fact that, in general, the poetic texts included in the course anthologies turned out more difficult to understand than prose texts, either literary or documentary. They also declared that the excerpts included in the course-pack for Estudios Culturales I were more complex because they had very little knowledge of British civilization prior to the 16th century; in contrast, they stated that were more familiar with the modern and contemporary periods and it was therefore easier for them to contextualize the information.

Students were also asked about the linguistic complexity they met in the reading of the texts; in the opinion of 18% these were easy; 32% regarded them as moderately complex; 36% defined them as complex; and 14% as very complex. It is important to notice that the Estudios Culturales I anthology included works in Latin and Old English, but their Present-Day English translations were provided on the facing page; nevertheless, the texts in Late Middle English and Early Modern English were presented in their original version, requiring further philological explanation to familiarize students with their linguistic and stylistic features. In the comments sections of the survey, some students remarked that the texts of the Estudios Culturales II courspack were in general much enjoyable to read as they were written in “modern English.” It is also relevant to consider that, in any case, by the second semester the consistency, duration, and quality of the stakeholders’ exposure to EMI was already considerable, resulting in that their average reading skills have improved greatly.

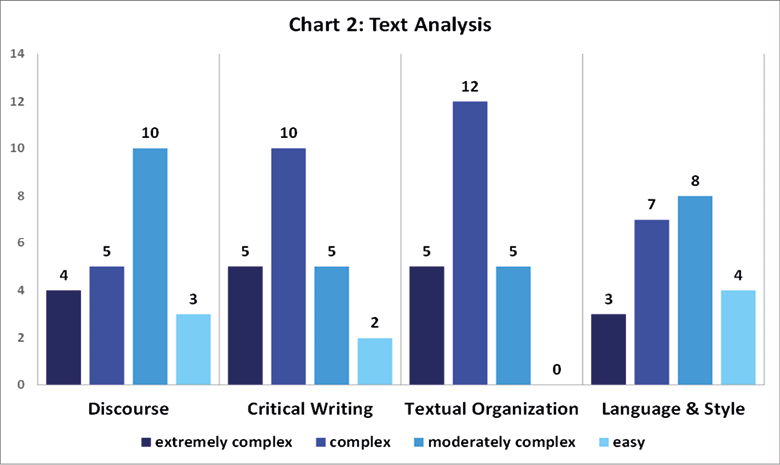

The third question of the survey was concerned the learners’ self-perception of the challenges related to their understanding of the texts’ discourse on the given cultural topics addressed. 14% considered they could do it with no difficulty; 45% declared it moderately complex; 23% found it complex; and 18% reported they had met serious obstacles with the conceptual analysis of the works, judging it as extremely complex. Actually, this kind of activity puts students’ analysis skills in English at play and was completely new for them. In the first weeks of Estudios Culturales I, some members of the group complained that they could hardly identify the author’s ideological stance on the historical topic approached in the texts unless it was explicitly stated, and that this was particularly difficult with literary texts. In contrast, they deemed this task as easier in the second semester. Therefore, the results of the survey point towards the positive effect of the EMI methodologies employed in the training, since students’ comprehension skills and cultural awareness improved through the academic year.

Questions four and five interrogated stakeholders about their capacity to produce independent critique in the frame of Cultural Studies in the form of short original critical essays, based on their analysis of the given texts. They were required to do this with expository clarity and pertinence, using the appropriate terminology, and in academic English. This task was perceived as easy by 9%; or moderately complex by 23%; however, it was regarded as complex by 45% and as extremely challenging by 23%. This evidences that curriculum-associated tasks involving independent thinking and the elaboration of original written works was one of the most demanding activities. This kind of exercises is cognitively challenging since it requires the activation of what authors define as higher-order thinking skills (Anderson & Krathwohl 2001; Álvarez-Gil, 2021). In order to articulate their individual appraisal of the cultural studies contents as part of the critical debate, learners must have assimilated the categories of cultural analysis and be able to produce academic pieces themselves, thus combining scientific content-knowledge and procedural skills of different cognitive order. The development of these professional abilities is achieved through intense practice, and since there are not two identical interpretations of one text, there are not two identical commentaries; subsequently, students need continuous, individualized feedback on their academic performance. Learning and teaching the mechanics of critical writing is one of the most time-consuming tasks in these courses’ programs. With this purpose, students are trained in commentary composition in class, and must also submit one mandatory essay as their mid-term assignment both in Estudios Culturales I & II. They have also the chance to turn in more pieces of works for extra assessment. The critical commentary activity is a powerful and valuable tool to check learners’ progression in the acquisition of academic competences, and it scores the 55% of the grade in the final exam. In connection with this, the interviews revealed that several students reckoned they felt “overwhelmed” during the first semester when it came to written assignments, and that their self-confidence was hindered as they deemed their language skills “insufficient to get good grades.”

The same self-doubt feeling applies to students’ perception of their writing abilities to structure their writing logically according to the stylistic rules of essay writing. In response to question five in the survey, only 9% found it easy to do; 23% admitted to having some difficulties; 45% considered it complex; and 23% considered it extremely complex. The most pessimistic students reported that they felt poorly prepared to advance a thesis statement and defend their claims convincingly in terms of logic, concision, accuracy, and pertinence, and not only in English but also in Spanish. These responses demonstrate flaws in the students’ educational background beyond the specific field of EFL/L2, yet they are also a good indication of first-year’s increasing ownership of their own development.

The sixth question was directly connected with the last two; concerning the mechanics of writing, students regarded producing grammatically and syntactically correct texts in academic English as easy 14%; moderately complex 32%; complex 36%; and as very complex 18%.

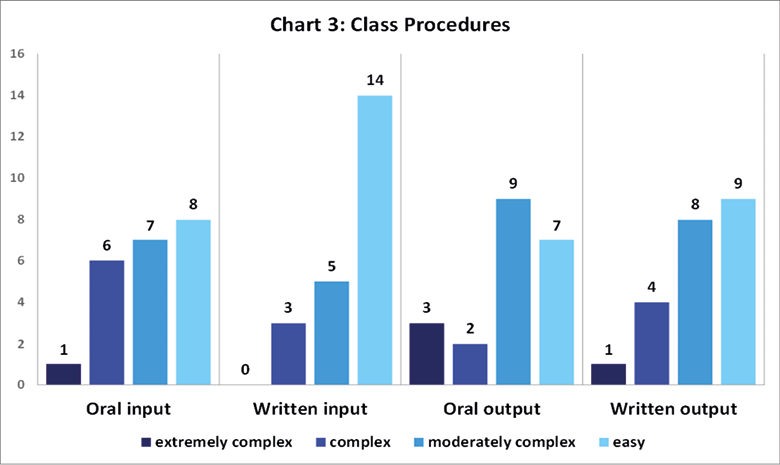

Items seven to ten surveyed the challenges met with EMI class procedures. In relation to issues with oral instruction in English, in item seven, learners rated the understanding of the oral input offered (class explanations, procedural information, debates, etc.) as easy 36%; moderately complex 32%; complex 27%; and 5% considered the classes very complex. As for the assessment of the difficulty in the understanding and assimilation of the written material used in the course (other than the anthology of texts), item eight indicates that 64% considered it easy; 23% regarded it moderately complex; and only 17% reported difficulties in working with it, with no student disapproving the task as extremely complex.

Questions nine and ten covered students’ views on their own communicative abilities to engage in EMI class dynamics. In regard of stakeholders’ perception of the complexity of carrying out oral interaction with peer students and the lecturer during the class sessions and consultation hours, 33% considered it was easy to express their ideas, present their points of view in the class debates, contribute information, ask questions and offer comments; 43% could do it with moderate difficulty; 10% found it complex; and 14% considered it extremely complex, to the point that in some cases they were reluctant to participate as they lacked the confidence to speak English in public because of their individual language issues (fluency and accent problems, etc.). Item ten assessed the written version of these interaction procedures; it is important to notice that due to the repeated malfunctioning of Collaborate Ultra and the large number of people in the hybrid class (with approximately 30 online assistants), many students often resorted to writing in the class chat when they could not use the micro/audio devices, this increasing somehow artificially the average frequency of in-class written communication in comparison with past terms. Although some students acknowledged their anxiety about their oral performance in class interaction, the results about indicate that they were less hesitant to write in English, and so 45% of stakeholders answered that they had no problems with written participation, 36% found it moderately complex; 18% saw it as complex; and 5% indicated it was extremely complicated for them.

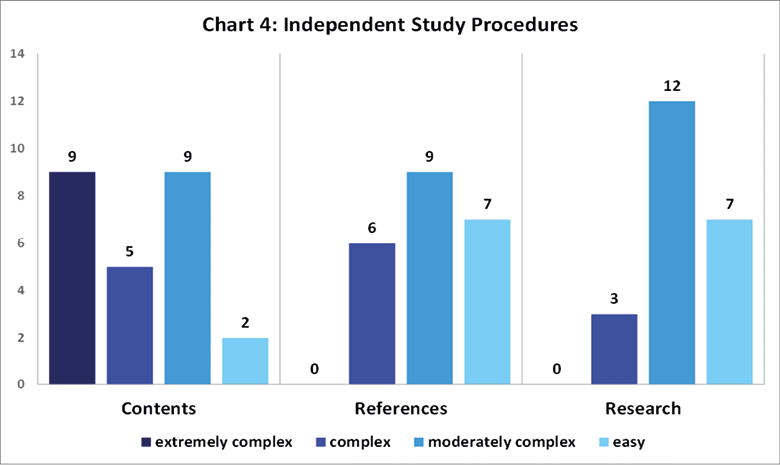

Items eleven to thirteen focused on individual study dynamics in these EMI courses. Stakeholders’ opinions regarding the complexity of working in English show that 9% considered it easy; 41% moderately complex; 23% complex; and 27% saw it as extremely complex. In the comments sections, informants expressed their concerns about not having received consistent training to study intellectually demanding matters in English on their own, as they had no previous experience with not being assigned homework or short task-based projects to be presented in the class immediate revision. For 50% of the group, their independent study hours presented them with problems because, contrarily to expectations based on their former educational experience, there was no single manual or textbook for the whole course. Even though three fundamental cultural history manuals are recommended, the course resorts to a wide variety of information and reference sources, and likewise memorizing data was important but obviously not the only goal in a subject course promoting independent, critical thinking. Therefore, students claimed that their learning progression was conducted at a slow pace. Some of them also stated that they felt uneasy about using the appropriate the content-specific and professional terminology of cultural studies and historiography when elaborating summaries, study notes, concept maps, etc. in English on their own. Once more, they declared this had been hard on them especially in the earlier stages of the first semester, but that they were more at ease in Estudios Culturales II.

In response to the twelfth question, informants reported that the consultation of the recommended course bibliography in English had been easy in 32% of the cases; moderately complex in 41%; complex in 27%; and no informant qualified it as extremely complex.

Item thirteen interrogated learners on their skills to do autonomous research in English to seek information and reference bibliography other than that offered as course material in the courses’ digital platform: 32% deemed this as easy; 55% as moderately complex; 14% as complex; and no one considered it extremely complex.

The last item of the survey asked the participants directly about the learning aspects of the course they considered most complex. There were 20 answers, out of which 90% stressed that mastering critical writing in academic English had been the most challenging one. 70% of these recognized they had not been trained to assess texts critically on their own before, since the model of text commentary they had practiced in secondary education differed greatly from the one used in Estudios Culturales. For some learners, this was the first time they were required to put critical abilities and independent thinking skills at work for the interpretation of primary sources. They reported having issues with the identification of the texts’ discursive strategies and the logical arrangement of the essays they wrote on them. Also, 30% declared to possess poor knowledge of universal history, and remarked that they had to invest much time in studying history contents that were already familiar for their peer students.

Figure 1. Textual understanding

Figure 2. Text analysis

Figure 3. Class procedures

Figure 4. Independent study procedures

III.4. Discussion

The findings presented above are consistent with studies conducted internationally indicating that the students of tertiary education EMI courses share the impression that they are not fully competent for these programs. This belief affects undergraduates even in places where bilingual education has a solid tradition and EMI has been established for long (Macaro et al., 2018, p. 53). In the case study presented, the fact that practically 50% of the informants declared that they felt not fully prepared to study the cultural history of English-speaking societies in English reveals the shortcomings of the pre-college training received. This perception is coincidental with lecturers’ appraisal of the situation of higher education EMI programs in Spain, as they consider that the linguistic barriers typical of this learning environment are difficult to overcome (Doiz et al., 2013). In fact, our informants perceived these Estudios Culturales courses as “quite demanding” because there was “too much material to study in English,” and suggested reducing the number of texts included in the course anthologies for the future. In this regard, it is also worth noticing that a large number of the stakeholders admitted that they had not read the courses descriptions (available through the university website and the course digital platform) before choosing to join the English Studies program, only to find out that EMI was in full operation from the very start. These participants had erroneously assumed that the instruction would be “at least partially delivered in Spanish.”

EMI in English Studies programs requires total linguistic immersion and a high-level degree of language awareness that is not required in other scientific areas, which is hard on first-year undergraduates. Our students informed that the estimated home workload dedicated to the Estudios Culturales courses oscillated between 4-10 hours per week, and half of this time was devoted to work on language issues. In order to help trainees adapt to the courses’ EMI didactics, the less proficient ones were especially encouraged to compensate for their educational deficits and bridge this gap in different ways. The records of this research indicate that stakeholders met no significant challenge in the understanding of the class input, as they could follow the oral explanations and in-class activities, and read the bibliographical material with low or moderate difficulty, as the answers to items seven and eight show. The survey also reveals an acceptably positive self-image concerning their in-class performance both oral and written; students considered that they could interact fluently both by speaking and writing during the sessions, as stated in items nine and ten. This has to do with the fact that learners counted on that the standards of correction and accuracy were more relaxed during class sessions than for more formal written assignments. They regarded receiving immediate oral feedback on errors during their class performance as helpful and encouraging. It is also worth noting that this more individualized monitoring of students’ in-class performance was possible because of the limited number of people in the classroom (6-14) in this academic year; the average pre-COVID class groups numbers of 40-50 people would not allow for it.

Regarding the development of analytical skills, students’ self-perception was less positive. According to the data gathered, they considered they may possess the hermeneutic basis and know how to use the suitable interpretive strategies for the task, but found it hard to express the results of the analysis in the required format of the critical essay. Stakeholders expressed their disappointment with their pre-college experience in critical writing: some of them admitted that either in English or Spanish, they felt capacitated to summarize and paraphrase texts, but could not discuss them in their cultural and historical contexts. This level of philological expertise was one of the key learning goals of the courses, and it had to be gradually achieved as it requires the consistent practice for the interiorization of essay writing strategies. In this sense, it is understandable that some stakeholders experienced frustration during the first months. They observed that the refining of their analytical reading skills took place much sooner than the improvement of their production skills, and this unbalance unsettled them. In the course of 3 of the 6 personal interviews conducted, 4 participants declared that they were now aware that the secondary education training in English “had failed them.” Also, 5 of them added that they did not feel confident at all they could produce solid written academic essays until the end of the first semester, and that the essay section included in the final exam of Estudios Culturales I had taken them twice as long as the completion of the other half of the test, consisting in elaborating short definition entries for several cultural history topics studied. This was particularly problematic in the case of Estudios Culturales I, when some learners felt so insecure about their EMI academic capabilities that relied too much on the bibliography consulted, sometimes verging on flagrant plagiarism. Rather that submitting their own essays, they preferred to replicate literally what they thought to be the opinions of authoritative sources -- even though sometimes these sources might be not very academically commendable, as is the case of Wikipedia, amateur and personal websites, essay-writing aid service websites, blogs, etc. Actually, it has been one of the most recurrent complaints among newcomer students over the years that there are no textbooks for these courses. They claim they cannot find suitable essays and commentaries on the specific excerpts included in the course anthologies that they could in turn use as models to memorize and reproduce. This is a sad consequence of their lack of training in the production of independent thinking-based text in English, and so it takes time to orient them towards developing their English writing skills and trusting their own critical aptitudes to produce academic material of their own authorship.

Although, in most cases, negative beliefs about their critical writing skills changed gradually through the term, the process of adaptation involved a substantial effort on the students’ part, and this no doubt affected their perspectives on English Studies as an academic area. On a positive note, answers to item 14 of the questionnaire, where stakeholders could add opinions freely, stressed that even though developing critical skills in academic English was the most arduous part of the training, they felt the global experience of the courses had endowed them with new metacognitive abilities, and that by the second term of Estudios Culturales their anxiety levels had decreased. Finally, the analysis of students’ responses to the dynamics and procedures of individual study expresses that they did not confront significant difficulties with independent learning in English once they got used to EMI. The results demonstrate that they could manage both contents and language-related issues.

This relates to the students’ own sense of accomplishment concerning the learning goals set for the Estudios Culturales courses: to gain the background knowledge to address complex contents in their original language, being attentive to the nuances of cultural analysis, and to be able to engage with them critically. In this regard, 1 of the interviewed remarked that taking the two Estudios Culturales courses had made her aware that “there are no neutral texts” in the rendering of history, and that therefore “one must be careful when assessing those texts in the present.” A second participant informed she felt know comfortable with her language and critical skills to “make sense of the texts in their context,” as she had found out that being trained in the techniques of close reading had “helped her detect that the authors’ approaches could be biased by their political, religious, class or gender prejudices.” The comments volunteered by students in response to item 14 of the questionnaire also stressed that at the end of the school year they felt intellectually equipped to assess the texts’ discourses on controversial topics such as nationalism, colonialism, imperialism, ethnocentrism, racism, migration, and other cultural constructions.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

From the very start, the students taking the two Estudios Culturales courses were well aware that the teaching of the English language was not the proper objective of these classes, but they were all the same conscious of the advanced level of proficiency in English necessary for attaining the learning goals. In the first two weeks of the Estudios Culturales I, first-years reported they had detected a considerable gap between the language competences they had acquired at their secondary education stage and what they understood was the adequate background to specialize in English Studies. The results of the research conducted show that after two semesters of consistently resorting to EMI teaching strategies, both face-to-face and online, and thanks to the use of course materials in the target language, the group’s average academic skills advanced considerably. The comparison of the final grades reports that 72% passed Estudios Culturales I, whereas 86% completed Estudios Culturales II successfully. This corroborates the widely spread idea that success in EMI programs largely depends on the accumulative effect of the individual’s exposure to the instruction in the foreign language. It is observable that in the study case presented, reading comprehension skills develop less in comparison to writing abilities, but the massive reading had a very positive impact on students’ own writing, as they learnt appropriate vocabulary and interiorized the formal structure of expository texts. Consequently, the quality of the essays they submitted for Estudios Culturales II was noticeably better than their first attempts in Estudios Culturales I. Actually, some of the informants interviewed declared that they had mixed feelings on this question; for 3 of them the experience had been “rewarding in the end,” even though during the first semester of Estudios Culturales they had doubts about the effectiveness of the methodology; on the contrary, the other 3 informants declared that from the beginning they understood that although EMI total immersion was demanding for them, it was the only way to “not repeat the failed methodology of the English classes in secondary education.” This confirms that newcomer undergraduates trained with EMI pedagogy develop metacognitive skills and gain ownership on their own education process.

First-year undergraduates in English Studies are unsure of their proficiency with EMI, and so motivating and triggering learners to use the language creatively is crucial. As this study case shows, and due to the special metalinguistic nature the English Studies program, enhancing their written production skills is considered by students as the most challenging aspect of their training. A widely spread feeling of insecurity emerges from being compelled to perform learning tasks in a language they do not master yet. In the case of English Cultural Studies, learners can be quite reluctant to depart from the authoritative interpretation of literary and historical works they can consult in manuals because they do not trust their own hermeneutic skills, which in turn are impended by the trainees’ self-perceived limited proficiency in academic English. Some suggestions for improvement can be made in this respect. Thus, it would be advisable to offer beginners more hours of total language immersion. Further, these learners would also greatly benefit from the implementation of academic writing workshops and seminars in the earliest stages of English Studies programs. These could give the less proficient students a much-needed language support by working in parallel to the core content-specific subject courses. For instance, by taking advantage of the ICT it would be possible to offer them tutorials and webinars that could be taken at one’s own pace; additionally, receiving aid from the so-called “writing labs” consulting services for academic writing, after the fashion of the ones functioning in foreign campuses, could be an advantageous resource to upgrade their academic communicative competences.

The feedback this study case provided will no doubt contribute to reorient those EMI class strategies that proved insufficient to meet beginner students’ learning challenges and educational needs in the future. The information gathered has been very valuable to understand the learning scenario of Spanish universities, and to detect the flaws in the training programs that, despite the long tradition of using EMI for English Studies, still need to be addressed.

V. REFERENCES

Aguilar, M., and R. Rodríguez (2012). Lecturer and student perceptions on CLIL at a Spanish university. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 15(2), 133-197.

Álvarez-Gil, F. J. (2021). Essential Framework for Planning CLIL Lessons and Teachers’ Attitudes Toward the Methodology. In M. L. Carrió-Pastor & and B. Bellés-Fortuño, (Eds.), Teaching Language and Content in Multicultural and Multilingual Classrooms: CLIL and EMI Approaches (pp. 315-338). Cham: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

Ballester-Roca, J. & Spaliviero, C. (2021). CLIL and Literary Education: Teaching foreign languages and literature from an intercultural Perspective. The results of a case study. In M. L Carrió-Pastor & and B. Bellés-Fortuño, (Eds.), Teaching Language and Content in Multicultural and Multilingual Classrooms: CLIL and EMI Approaches (pp. 225-251). Cham: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Bazo, P., González, D., Centellas, A., Dafouz, E., Fernández, A., & Pavón, V. (2017). Linguistic policy for the internationalization of the Spanish university system: A framework document. Madrid: CRUE.

Bloom, B., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. New York: Longman.

Carrió-Pastor, M. L. (Ed.). (2020). Internationalising learning in higher education: The challenges of English as a medium of instruction. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Carrió-Pastor, M. L., & Bellés-Fortuño, B. (Eds.) (2021). Teaching Language and Content in Multicultural and Multilingual Classrooms: CLIL and EMI Approaches. Cham: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Dafouz, E. & Núñez, (2009). CLIL in higher education: Devising a new learning landscape. In E. Dafouz, & M. Guerrini, (Eds.), CLIL across education levels: Opportunities for all (pp. 101-112). Madrid: Richmond-Santillana.

Dafouz, E., & Camacho-Miñano, M. M. (2016). Exploring the impact of English-medium instruction on university student academic achievement: The case of accounting. English for Specific Purposes, 44, 57–67.

Doiz, A., Lasagabaster, D. & Sierra J. M. (Eds.) (2013). English-Medium Instruction at Universities: Global Challenges. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Duraisingh, L.D. (2021) Promoting engagement, understanding and critical awareness: Tapping the potential of peer-to-peer student-centered learning experiences in the humanities and beyond. In S. Hoidn & M. Klemenčič (Eds.), The Routledge International Handbook of Student-Centered Learning and Teaching in Higher Education (pp. 123-138). London: Routledge.

Eurydice Report (2017). European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. Key data on teaching languages at schools in Europe -2017 edition. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union.

Fortanet-Gómez, I., & Räisänen, C. A. (Eds.) (2008). ESP in European Higher Education: Integrating language and content. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Jiménez-Muñoz, A. (2016). Content and Language: The Impact of Pedagogical Designs on Academic Performance within Tertiary English as a Medium of Instruction. Porta Linguarum Monograph (1), 111-125.

Macaro, E., Curle, S. Pun, J. An, J. & Dearden, J. (2018). A systematic review of English Instruction in Higher Education. Language Teaching, 51(1), 36-76.

Martín del Pozo, M. (2015). Teacher education for content and language integrated learning: Insights from a current European debate. Revista electrónica universitaria de formación del profesorado, 18, 153-168.

Monterrey, T. (2003). Los estudios ingleses en España (1900-1950): Legislación curricular. Atlantis, 25(1), 63-80.

Muñoz, C. (2001). The use of the target language as the medium of instruction: University students’ perceptions. Anuari de Filologia, XXIII A 10, 71-82.

Muñoz, C. (2006). Age and foreign language learning rate. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Sancho-Esper, F., Ruiz-Moreno, F., Rodríguez-Sánchez, C., & Turino, F. (2016). Percepción del profesorado y alumnado sobre la docencia en inglés: Aplicación AICLE en la UA. In M. Tortosa, S. Grau, S., & J. D. Álvarez, (Eds.), Investigación, Innovación y Enseñanza universitaria: Enfoques pluridisciplinares (pp. 353-368). Alicante: Universidad de Alicante.

Santoyo, J. C., & Guardia, P. (1982). Treinta años de Filología Inglesa en la universidad española. Madrid: Alhambra.

Received: 8 September 2021

Accepted: 30 September 2021