EMI and Intercultural Competence at University of Alcalá: The case of the Master’s Degree in Teacher Training

Universidad de Alcalá, Spain

cristina.tejedormartinez@uah.es

Universidad de Alcalá, Spain

ABSTRACT

The use of English as a Medium of Instruction to teach subjects other than English is widely spread across European higher education institutions. The University of Alcalá has been working on the implementation of English-Medium Instruction (EMI) for decades now. The internationalisation process accounts for the increasing number of studies both at undergraduate and postgraduate levels taught in English. The response of international students has been positive considering the University of Alcalá one of their favourite Spanish destinations. The interaction of local and foreign students evidences the need to raise awareness towards the intercultural competence as part of the Master’s Degree in Teacher Training, so that learners will feel comfortable in a different language and culture and contribute significantly not only to the labour market but also to dialogue and living together. In this article, the authors report on how this is done in one of the compulsory courses of this specific Master’s Degree: Complementary Training in English Studies.

Keywords: EMI; Intercultural Competence; University of Alcalá; Teacher Training for Compulsory and Upper Secondary Education, Vocational Training and Foreign Language Teaching; Complementary Training in English Studies.

I. INTRODUCTION

I.1. Defining English-Medium Instruction

The concept of English-Medium Instruction (henceforth EMI) is relatively recent, juxtaposed with another phenomenon, Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), and still there is no consensus about its definition, as Kling (2019) points out:

While there is a great deal of debate as to a specific definition, English as a medium of instruction (EMI) typically refers to the use of English as the language of teaching and learning for academic content courses (e.g., chemistry, biochemistry, sociology, political science) in contexts where English is not the natural or standard language of instruction […]. In most cases, the learning outcomes for EMI courses focus on disciplinary competences; the language itself is not being explicitly taught. (2019, p. 2)

In turn, Macaro (2018, pp. 16-19), after analysing the different notions around the idea of EMI and the observations provided by various scholars, proposes the following definition: “The use of the English language to teach academic subjects (other than English itself) in countries or jurisdictions where the first language (L1) of the majority of the population is not English” (2018, p. 19). As the author explains, this definition opens several questions: “How much use? What kind of use? Used by whom?” (Macaro, 2018, p. 19). All these three questions relate directly to the core elements involved in the phenomenon of EMI. In the first place, the amount of the use of English in the teaching process: whether English will be used in all the sessions, only in the teacher’s presentation, in materials and resources (in all of them or only part), etc. In the second place, the kind of use implies, for example, that explanations are in English, but classroom management is in L1, or part of the contents are explained in English and others in L1, or contents are in English and students’ work in L1. Thus, different languages can be used while teaching. Finally, we should consider if both, teachers and students, will be using English and in which situations.

However, we have not addressed several problems that arise such as the language proficiency needed by both groups involved, training to support this way of teaching, the financial resources needed, etc., and some other questions regarding the possibility of separating completely the teaching of content from the teaching of language or the effectiveness in learning English in EMI programmes. Research to identify the difficulties has been carried out. For instance, Vu and Burns (2014, p. 5) point out some of the fifteen common problems identified by Smith (2004, as cited in Coleman, 2006) in European higher education EMI programmes: the need to improve language skills for local students and staff and the supply of competent English-speaking content lecturers, though these are not the only ones that should be considered.

There has been a significant growth of EMI courses, which is clearly related to the internationalisation strategies in which most universities are involved. Shohamy (2013) states that learning through the widespread EMI approach at universities is:

A reflection of the combination of two power entities: on the one hand, the power of the English language at this day and age, a language that a large number of learners seek to acquire given the belief that it will provide access to central bastions of society and, on the other hand, the power and status associated with the prestige of universities that grant degrees and provide access to the workplace. (2013, p. 201)

All in all, the implementation of EMI should be carefully planned by the institutions in order to get the expected results, because the spread of EMI at higher education does not imply success. In fact, the effectiveness of EMI approaches at universities poses problems about the levels of academic knowledge acquired by students. Several authors (Coleman, 2006; Tamtam et al., 2012; Shohamy, 2013; Macaro, 2018, among others) concentrate not only on the advantages and possibilities of developing EMI programmes, but also on the disadvantages that have been noticed, and point out that the theoretical analysis of the issues involved should continue in order to evaluate its effectiveness.

I.2. Internationalisation at University of Alcalá

The spread of English as the vehicle of communication all over the world is part of the globalisation process that has been taking place since the last quarter of the twentieth century, although, as Kachru explains (1996, p. 2), this global role of English was predicted for over two hundred years ago by John Adams, the second president of the United States. The English language has come to occupy a unique position due to the number of non-native users, that is “English as its other tongue” (Kachru, 1996, p. 3), and to its increasing importance in the social, economic, scientific and cultural spheres. In fact, Coleman (2011, p. 18) states that English plays an important role in “increasing employability, facilitating international mobility (migration, tourism, studying abroad), unlocking development opportunity and accessing crucial information, and acting as an impartial language”.

The status of English as a global language has been reflected in the tendency to offer courses in English at different European universities, that is, the promotion of EMI in higher education. EMI in Europe is seen as a means of boosting intercultural knowledge as well. Subsequently, the participation in foreign exchange programmes within the domain of higher education has been encouraged (Tamtan et al., 2012). The well-known project developed within the European Union, Erasmus (European Region Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students) has contributed to the cultural exchange and awareness of other countries which are part of the European Union. The programme has been successful all over Europe, especially in those countries receiving the higher number of exchange students; namely Spain, France, Germany, United Kingdom and Italy, according to the European Commission (2012). As Macaro explains, most Erasmus students in the 1980s and 1990s attended courses taught in the language of the host institution, but “there has been a gradual shift from attending courses in the language of the host country to attending courses taught through the medium of English” (2018, p. 50). Certainly, there has been a shift in the idea of European plurilingualism, because at a certain point English was granted a prominent position as language of instruction. In fact, English, being considered a global language, has become the lingua franca of education, also in European higher education, as Ferguson already recognised, when the Erasmus project was starting, claiming that “English is widely used on the European continent as an international language. Frequently conferences are conducted in English (and their proceedings published in English) when only a few of the participants are native speakers” (1981, p. xvii).

One of the first experiences of EMI in European higher education took place in the mid-1980s at Maastricht University, when a first-degree programme in International Management taught mainly in English was implemented (Wilkinson, 2013, p. 4). Many other projects have followed since then, as Coleman contends, in the last fifteen years, “English-medium teaching in Europe universities has shown exponential growth, initially in maste’s courses but increasingly also in undergraduate degrees” (2006, p. 6).

The desire of internationalisation of universities has triggered the use of English in higher education and in academia (Lasagabaster & Doiz, 2021, p. 1) and subsequently, EMI is gaining momentum. Spain is no exception to this, and the University of Alcalá proves to be a good example of the implementation of internationalisation plans which include courses in English, participation in study abroad programmes and the establishment of overseas partnerships in order to achieve international positioning. The mobility of the academic staff and the students is a key element in this process. In fact, the internationalisation plans were part of the strategic schemes of most universities, as the study carried out at seven hundred and forty-five universities confirmed (Egron-Polak & Ross, 2010). Recently, the University of Alcalá has created the International Summer and Winter School for both national and international university and pre-university students who want to have a multicultural experience.

The University of Alcalá is considered one of the major international destinations among undergraduate and postgraduate students, probably because of the environment where the University is set, the cultural and social activity of the city, its proximity to Madrid, the good reputation of the University, the desire to improve students’ level of Spanish, and also thanks to the number of courses that are provided in English. In fact, according to the QS WUR (World University Ranking), the University of Alcalá is the second Spanish public university in the ranking in the attraction of international students. Evidence of its appealing force is the fact that, in the latest three academic years, out of the total number of students at university, nearly one sixth of them was originally from foreign institutions. The difference between the incoming students and the outgoing is also remarkable, since we receive nearly ten times the number of students we send abroad. The distribution can be seen in the following table:

Table 1. Distribution of incoming and outgoing students

| 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incoming | 5,523 | 4,751 | 5,184 |

| Outgoing | 539 | 513 | 547 |

| Total | 28,067 | 29,063 | 29,015 |

Out of the forty-four official degrees in the University of Alcalá, twelve offer most of their teaching in English: Degree in Economics and International Business, Degree in English Studies, Degree in Modern Languages and Translation, Degree in Primary Education, Degree in Computer Engineering, Degree in Computer Science Engineering, Degree in Electronic Communications Engineering, Degree in Electronics and Industrial Automation Engineering, Degree in Information Systems, Degree in Telematics Engineering, Degree in Telecommunication Technologies Engineering, and Degree in Telecommunications Systems Engineering. The Polytechnic School is the one which incorporates subjects taught in English in the highest number of degrees, up to eight. In turn, the Faculty of Arts and Humanities participates with three degrees, and the Faculty of Economics, Business and Tourism offers another degree, in both cases in the bilingual option, at least half of the credits of students’ plan are taught in English.

Regarding the sixty-seven official master’s degrees, eight offer part of their teaching in English and this fact is clearly indicated in the specific access conditions for students, where an English level certificate is required: American Studies, Industrial Engineering, Photonics Engineering, Telecommunication Engineering, Finance and Banking, International Business Administration, Teacher Training for Compulsory and Upper Secondary Education, Vocational Training and Foreign Language Teaching (English section) and Teaching English as a Foreign Language. The two Faculties and the School mentioned above, which offer the undergraduate degrees in English, are also the ones involved in the use of English-Medium instruction at the master’s level.

Several master’s degrees in the Health Science area indicate that the teaching languages can be both English and Spanish, although English is not clearly established as a compulsory working language, for example in Manual Physical Therapy, Drug Discovery, General Health Psychology, where English is used in part of the bibliography of the subjects in this study; also for seminars and for students’ papers, whereas in Microbiology applied to Public Health and Infectious Diseases Research, Therapeutic Targets of Cells Signalling: Research and Development, the English language is occasionally used.

Similarly, in the Social and Legal Sciences field, English is also considered subsidiary working language in some master’s degrees, such as Accounting and Auditing and their Effects on Capital Markets, Conference Interpreting for Business, International Human Rights Protection, Management and Change Management, since several of the compulsory and optional courses are taught in English. In the Science area, some master’s degrees also incorporate the use of English in their teaching, either in several seminars that are taught in English, or in the bibliography used and, therefore, knowledge of English is necessary to follow the courses: Ecosystem Restoration, Chemistry for Sustainability and Energy, Geographical Information Technologies, Physical Anthropology: Human Evolution and biodiversity, and Science and Technology from Space.

It follows from the above description that the reality regarding EMI in the different undergraduate and masters’ degrees in the University of Alcalá is varied and relates directly to the questions suggested by Macaro (2018, p. 19) in his definition of the phenomenon: the amount of the use of English in the teaching process, how the use of English is organised by the participants and who will use English. A range of situations can be encountered, from a full use of English by both participants and in the whole teaching process, to the deployment of English only in the bibliography and materials that are part of the courses. Certainly, teachers play different roles in the EMI education process in this particular context possibly related to their own linguistic competence. In order to promote EMI, the University is taking several measures. Members of the teaching staff can enroll in free English language courses to improve their proficiency and, therefore, encourage them to participate in the EMI programmes. Besides, the University usually rewards these teachers in their course load count. The free English language courses are also open to the administrative staff so that they can communicate with international students.

Regarding national students attending courses at University of Alcalá, the great majority come from the Autonomous Community of Madrid in which a significant number of Primary and High Schools offer bilingual education. In fact, the so-called Bilingual Programme was implemented in the Autonomous Community of Madrid in Primary Education in 2004 and it was made extensive to Secondary Education schools in 2010. Since then, it has been gaining ground steadily. In fact, some students decide to continue their studies at tertiary level also through English and, subsequently, join EMI courses. Therefore, the entry requirements in EMI programmes are established for all students at undergraduate and master’s level. The University works in raising EMI at all levels with a twofold purpose: the international promotioni of the institution and the completion of levels of excellence necessary for an adequate academic and professional training of students.

It is a fact that EMI is widely integrated in the undergraduate and masters’ degrees. The following table shows the number of incoming international students enrolled in face-to-face undergraduate degrees in all the Faculties and Schools at the University of Alcalá during the latest three academic years:

Table 2. Incoming international students at UAH

| 2017-2018 | 2018-2019 | 2019-2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| School of Architecture | 72 | 43 | 76 |

| Polytechnic School | 28 | 44 | 44 |

| Faculty of Sciences (Biology, Chemistry, Environmental Sciences) | 24 | 32 | 30 |

| Faculty of Economics, Business and Tourism | 163 | 167 | 175 |

| Facutlty of Law | 42 | 38 | 36 |

| Faculty of Education | 16 | 13 | 38 |

| Faculty of Pharmacy | 17 | 18 | 21 |

| Faculty of Arts and Humanities | 287 | 236 | 269 |

| Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences | 52 | 45 | 45 |

When reading the table, differences in the number of incoming students can be easily observed: the Faculty of Arts and Humanities records the highest number by a wide margin over the next one, the Faculty of Economics, Business and Tourism. Both Faculties offer degrees in English or mostly taught in English, but the Faculty of Arts and Humanities also attracts international students that want to learn the Spanish language and culture, being this an essential factor to partially explain the difference in numbers. Although the School of Architecture does not offer degrees in English, it occupies the third position. The reason that explains its success is that a good number of incoming students come from Spanish speaking countries. On the contrary, the Polytechnic School, which teaches several undergraduate degrees and three masters’ degrees using English as a language of instruction, does not attract an important number of international students. In fact, it is in a similar range with other Faculties that do not offer English teaching in their degrees. Nevertheless, it can also be pointed out that the number of international students in this School have risen considerably, from 28 to 44. As we have mentioned, the University of Alcalá also attracts international students that come to join the courses offered in Spanish or even combining EMI courses with others taught in Spanish.

Students come from a wide range of countries from different backgrounds and expectations. The number of students joining the University of Alcalá either physically or virtually in master’s degrees, PhD programmes and postgraduate courses in general is even higher, which explains why the institution welcomes over five thousand international students every year. As Saarinen and Nikula pointed out, “international programmes usually involve culturally and linguistically heterogeneous student populations, with varying levels of proficiency in English and experience with English-medium instruction (EMI)” (2013, p. 132). The relationship between cultural contents and English as a medium of instruction will be addressed in the next section.

II. INTERCULTURAL COMPETENCE AND ENGLISH-MEDIUM INSTRUCTION

II.1. The significance of Intercultural Competence

Language and culture are intrinsically interwoven. Learners cannot completely master a language if they are unaware of the environment where the language is spoken. Even if there are some aspects shared by all languages, which are often known as linguistic universals, there are traits that are specific of a given speech community. The cultural aspects are reflected through the specialisation in the lexicon, among others. Thus, it is easily understandable why Eskimo languages have various denominations for snow, or why Galician has plenty of words for the different kinds of rain. The acknowledgement of this fact is essential to any person who uses the language if effective communication is pursued. In fact, knowledge of the culture is vital to business, trade and commerce stakeholders, as well as to linguists and translators, among many other users. In this vein, Franco-Aixelá warns that culture-specific items can pose problems to translators since they may not find an equivalent in the target language. He regards a culture-specific item as “the result of a conflict arising from any linguistic represented reference in a source text when, transferred to a target language, poses a translation problem due to the nonexistence or to the different value (whether determined by ideology, usage, frequency, etc.) of the given items in the target language culture” (Franco-Aixelá, 1996, p. 57).

The adoption of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages by the Council of Europe (CEFR, 2001) gave greater importance to cultural aspects in foreign language education. According to Reid, “the aim was to equip learners with the ability to communicate appropriately across linguistic and cultural boundaries in multicultural and multilingual Europe. Even though the CEFR emphasises the importance of developing ICC, it only gives general instruction” (2015, p.940).

In turn, Moran explains that the intercultural competence consists of “developing the ability to interact effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations, regardless of the cultures involved” (2001, p.111). Lussier adds that one of the components of the intercultural competence, what this author names as trans-cultural competence, is about one’s own perspectives, practices and products and those of other sociocultural groups. Thus, it implies “the integration of new values, the respect of other values and the valorization of otherness which derives from the coexistence of different ethnic groups and cultures evolving in a same society or in distinct societies while advocating the enrichment of identity of each culture in contact” (2007, p. 324).

Scholars now agree on the fact that that knowledge of the culture is a vital element that cannot be overlooked in foreign language teaching in order to promote the intercultural competence. Likewise, it has also been emphasised that it should be integrated in EMI. Furthermore, Aguilar considers that “Intercultural Competence (IC) should become a learning outcome in ESP and EMI courses” (2018, p. 25). Thus, teachers are essential mediators to help students to learn about the language, the beliefs, values and tenets of the culture behind the language and, in getting the knowledge, teachers and students will facilitate intercultural communication.

As seen in the introduction, EMI has been defined in a number of ways. A simple definition is provided by Schmidt-Unterberger: “Teaching non-language subjects through English” (2018, p. 528). The authors are teachers in the Master’s Degree in Teacher Trainingii in the subject Complementary Training in English Studies, where both EMI and the intercultural competence are in action. The subjects taught in this master are not properly about English, but pedagogy on how to approach teaching in general and the English language in particular.

II.2.Intercultural Competence in textbooks

Several authors have mentioned that there are different types of culture (Gómez-Rodríguez, 2015; Moran, 2001; Kramsch, 2014). In fact, both Moran and Kramsch distinguish between two kinds: Culture with a big C and culture with small c. According to Kramsch, “the speech habits of native speakers in formal, written, or academic situations were captured by the big C culture of literature and the arts, the speech habits of native speakers in normal conversations were captured by the little c culture of everyday life” (2014, p.403). Kramsch adds that until the 1960s the focus on foreign language learning was placed on big C culture. Thus, textbooks tend to depict this kind of culture and often misrepresent culture with small letters.

Likewise, Bocanegra-Valle (2015) and other scholars agree on this claim, since their studies on the intercultural element in textbooks confirm this idea. Even if textbooks are powerful resources to work on the intercultural competence, publishing houses fail to help students to achieve it. According to Bocanegra-Valle, it is not a significant aim in English for Specific Purposes textbooks and many of them attempt to give a certain impression of globality by introducing the word international in their titles (2015, p. 39).

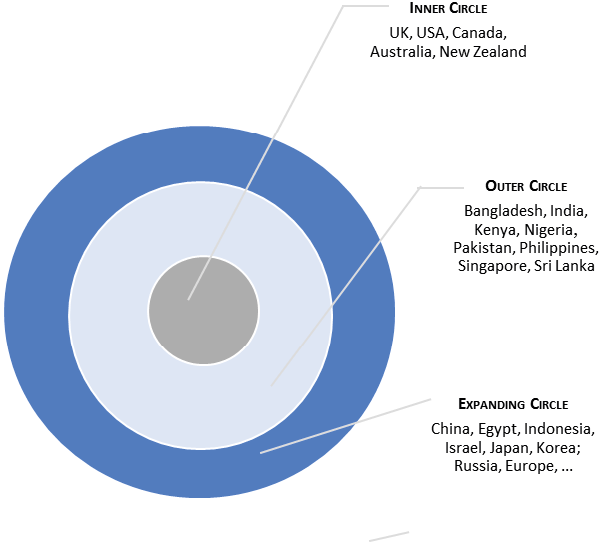

Another issue that needs to be addressed is the type of language variety and associated culture which is selected to be represented in textbooks. The question of which English should be taught is an essential one in EMI programmes too. There are several cultures associated with a particular language. Thus, English is spoken as a first language in United Kingdom, Ireland, United States of America, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. In the concentric circles of English proposed by Kachru (1985, 1996), the choice of countries in textbooks basically corresponds to the Inner Circle:

Figure 1. Adaptation of Kachru’s circles of English (Kachru, 1996, p.356)

Although Macaro (2018, p. 129) points out the value of Kachru’s model, he also explains that the model “has subsequently been critiqued because it is too heavily nation-based (Bruthiaux, 2003) and fails to identify the complex sociolinguistic and policy-driven realities within and between each of the circles”. In fact, the countries in the Outer Circle, where English is co-official with other languages and their cultures very rarely occur in textbooks.

Teachers are active ambassadors of the culture lying behind the specific variety they are teaching, since students will see the culture through their eyes. Thus, the function of language teachers is not only the transmission of information about a foreign country, but also the guiding of students through their own exploration of the reality to value and respect other cultures. In this way, according to Byram et al. (2002), the intercultural dimension is concerned with

- helping learners to understand how intercultural interaction takes place,

- how social identities are part of all interaction,

- how their perceptions of other people and others people’s perceptions of them influence the success of communication,

- how they can find out for themselves more about the people with whom they are communicating. (2002, p. 10)

III. THE CASE OF COMPLEMENTARY TRAINING IN ENGLISH STUDIES IN THE MASTER’S DEGREE IN TEACHER TRAINING

III.1. Master’s Degree in Teacher Training for Compulsory and Upper Secondary Education, Vocational Training and Foreign Language Teaching

The desire to be in line with the new demands of the labour market has led the University of Alcalá to the promotion of EMI, a practice that has been going on for decades now in Spanish higher education institutions, “in an attempt to meet the challenges of today’s rapidly changing globalised world” (Pavón-Vázquez and Ellison, 2021, p. 193). Following the university commitment to internalisation through EMI courses, the Degrees in English Studies and Modern Languages and Translation from the Department of Modern Languages have been using English as a medium of instruction in every single subject for decades, except for courses on French, German and Spanish. Likewise, most masters’ courses where the staff of the Department participate are taught in English. Thus, since 2010 the authors have been participating in the Master’s Degree in Teacher Training in the English section. The subjects in this master’s degree are not properly about the English language, but pedagogy on how to approach teaching in general, reflecting on all the aspects that need to be taken into account before planning a lesson to answer questions about the contents, materials, the timing and sequence, the target audience, the setting, the method, the objectives and competences and, once the lesson is designed, the evaluation process. Thus, teachers wonder about these elements represented in Figure 2:

Contents: What am I going to teach? And with what materials?

Timing: When is the teaching taking place and in what order are the contents and materials to be sequenced?

The target audience: Who are my students, what is their age, their level?

The setting: Where am I to teach?

The method: What approach am I going to follow?

Purpose: Which are the aims and competences?

Figure 2. Key elements in teaching planning

These elements surrounding the central idea of teaching planning, as can be seen in Figure 2, are vital to any act of teaching and so is the evaluation process that must take place to make sure the contents are assessed through appropriate instruments and to ponder on ways of improving every element that takes part in the process. Thus, the master covers all the aspects a prospective teacher must bear in mind to plan and carry out effective teaching. Gradually it will concentrate on issues that apply to any language teaching and, to do so, takes into account the tenets of foreign language teaching, with particular attention to the English language.

III.2. Complementary Training in English Studies and the Intercultural Competence

One of the subjects included in the Master’s Degree is Complementary Training in English Studies. As mentioned above, the course vehicular language is English. The syllabus includes some contents which are compulsory by the standing law, such as English as a global language, which is followed by a unit on the cultural component in languages. The main aim of this unit is to make prospective teachers aware of the necessity of teaching culture intertwined with grammar in the more holistic sense. There is no point in teaching lists of words of vegetables and fruits, for example, if we do not pinpoint the usual practice of purchasing fruit by pieces in Britain or letting students know that a pound is also a measure. Thus, great attention is paid to the achievement of the intercultural competence which is worked from a theoretical and practical point of view.

The Council of Europe (2014, p. 28) states that “intercultural competence is a pedagogical goal pursued through deliberate inclusion of specific activities for learning”. It is obvious that awareness towards the intercultural competence is a priority in the course and subsequently, a number of activities are aimed at increasing students’ awareness of the topic, so that they will introduce the intercultural competence in their learning outcomes once they start their teaching practice. Furthermore, the Council of Europe adds that “because intercultural competence involves not only attitudes, knowledge, understanding and skills but also action, equipping learners with intercultural competence through education empowers learners to take action in the world” (2014, pp. 21-22). This action will take place not only in their lives but also in others’. Our students are prospective teachers whose work will impact on the development of the new generations, so they are key participants in preparing their own students for a future professional career in a globalised world, where the intercultural knowledge will enable them to better understand otherness.

The Council of Europe (2014, pp. 20-21) provides an extensive list of items that are part of the different components of intercultural competence (attitudes, knowledge and understanding, skills and actions). In order to develop students’ intercultural competence several techniques are used in the subject Complementary Training in English Studies:

- Readings to make students aware of the cultural distance. In pairs, students are assigned the reading of an article on the topic, and they have to present the contents of the article to their partners in the following session. The authors of the articles are Spanish, like Coperías-Aguilar (2010), which allows students to reflect on the intercultural competence in a Spanish setting, but also foreigners, like Wen (2016), whose reading arises students’ awareness of other cultures apart from their own.

Similarly, the selected readings have another purpose: to explore their own intercultural identity as prospective foreign language teachers (Fernández-Agüero and Garrote, 2019) and the need for these prospective language teachers “to become aware of the multifaceted English world” (De Bartolo, 2019, p. 611).

- Role play. According to Reid (2015, pp. 942-943) “Role play is a very effective technique practicing sociolinguistic and pragmatic phrases, socio-cultural knowledge, but also non-verbal communication”. We share this opinion, and subsequently, students are given some situations to practice. For instance, in a restaurant in an English-speaking country, where the food restrictions are more varied because of the existence of a higher number of the population eating kosher, vegetarian, flexitarian, fruitarian or pescatarian. Likewise, both in restaurants and shops, but also in different means of transport, in some English-speaking countries pets are welcomed, especially those considered to be for emotional support. Although this practice is being adopted increasingly in Spain, it is not so common to see dogs, cats, or other pets on buses, planes, restaurants and shops. This is also a good opportunity to explore differences through role play.

- The technique of cultural capsule, which “demonstrates, for example a custom, which is different in two cultures” (Reid, 2015, p. 941). In the class, we discuss, for instance, main meals of the day, their timetable, their ingredients and methods of preparation. Thus, in the United Kingdom the main meal is in the evening and quite early to Spanish standards. We also deal with the rituals when offered food as a guest: whether you should accept immediately or a negotiation process begins, whereby the guest initially rejects the invitation to stay for dinner or to accept more food when sharing the table with their hosts in Spain, whereas in Britain this ritual does not necessarily take place, since the guest either accepts or rejects the invitation kindly from the very beginning. According to Reid (2015, p. 941), this activity, which “practices socio-cultural knowledge, sociolinguistic and pragmatic competences”, serves to reflect on differences. Therefore, divergences in table manners in the United States and Spain, for example, and also in some other habits are explored. For instance, sharing a salad, a starter or first course is quite frequent between friends and family in Spain, while in English-speaking countries you should ask first whether they would consider this practice acceptable.

- The comparison method, which is “one of the most used techniques for teaching cultures. It concentrates on discussing the differences between the native and target cultures” (Reid, 2015, p. 941). We practice this technique dividing the class in groups: some groups are provided with the situations in English and must discuss them in that language. Their partners receive the same situations in Spanish and must discuss them in Spanish. For instance, group A is given the following situation: “You ask your flat mate to clean up the kitchen that is in a mess after he/she used it last night”. In turn, group B gets this: “Tu compañero/a de piso dejó la cocina hecha un asco anoche, así que le pides que la limpie”. This is probably the only instance when Spanish is used as a vehicle of communication in class. Another situation for group A is: “You are wearing a T-shirt. You meet your friend, and she tells you how cool it is, what do you say?”, whereas group B receives this: “Llevas puesta una camiseta. Tu amiga te la ve y te comenta cuánto le gusta, ¿qué dices tú?”. Then, we reflect on the different discourse strategies that are used in both languages to request, demand or thank people. The findings are in line with previous studies (Cenoz & Valencia, 1996), whereby Spanish makes use of more direct commands, whereas English uses more indirect strategies.

- Final project. Students must write a final project designing a didactic unit that integrates the intercultural component. Thus, they can prepare their teaching unit with activities on festivities, habits, practices, etc. Very often they choose an environment they are familiar with and make use of their own experience in English-speaking countries. Students tend to design materials based on their stays in Ireland introducing Saint Patrick’s Day, Thanksgiving Day for those keen on the United States; the figure of Guy Fawkes with bonfire night is often recalled by students whose main stay was in England, while those staying in Scotland bring up the figure of Robert Burns and talk about Burns’ Night with haggis, nippies and tatties, and even a few of them acquainted with Australia culture may design a project on Maori art. Some other students choose other topics for their projects like sports that are rarely practised in Spain, such as baseball, rugby, cricket, curling, hurling, as they are practiced in an English-speaking country.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

The desire of internationalisation in higher education linked to the consideration of the English language as a global vehicle of communication has brought about the increase in EMI worldwide. Regarding the European higher education system, “English is clearly the dominant foreign language used in teaching at institutes of higher education in the EU countries. […] English is generally perceived to be the dominant language of teaching for the future” (Ammon & McConnell, 2002, p. 7).

The University of Alcalá is a good example of this phenomenon with twelve undergraduate degrees offering teaching in English, eight master’s degrees also including all or part of their subjects in English and other twelve master’s degrees incorporating the use of English in their teaching, either in seminars or in the materials and bibliography. As it has been explained, there is not a single scenario, but different approaches to EMI are being put into practice within the University of Alcalá. All in all, the implementation of EMI programmes at Alcalá University has proven to be successful, since it has become the second-ranking Spanish public university in attracting international students according to the QS WUR.

The integration of the intercultural competence is necessary in language teaching syllabi. Therefore, contrastive cultural studies, where traditions and culture-bound behaviour is covered, are needed to enable a good understanding. Besides, very often they go along with specific linguistic expressions that are to be uttered under certain circumstances in order to avoid social blunders. In fact, language and cultural practices are intimately connected and, therefore, the language must be learned within the culture where it is spoken.

We have presented the experience in Complementary Training in English Studies where the instruction is mediated through English. A relevant issue in the contents of the course is the students’ awareness towards the intercultural competence, since they are prospective teachers. As a way of conclusion, one can use the words by Byram et al. (2002, p. 6):

Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching involves recognising that the aims are: to give learners intercultural competence as well as linguistic competence; to prepare them for interaction with people of other cultures; to enable them to understand and accept people from other cultures as individuals with other distinctive perspectives, values and behaviours; and to help them to see that such interaction is an enriching experience (Byram et al., 2002, p. 6).

Indeed, one of the aims in this subject is to promote the knowledge about different cultures through the use of English as a Medium of Instruction. The focus is not on upgrading students’ proficiency of English, but on showing sensitivity towards other people’s cultures fostering reflection on the importance of acquiring the intercultural competence. Our intention is that these prospective teachers will combine both, intercultural competence and the use of the English language, in their teaching practice. Thus, this training will help the development of future professionals and will contribute to creating democratic citizens within a culturally diverse world.

V. REFERENCES

Aguilar, M. (2018). Integrating intercultural competence in ESP and EMI: From theory to practice. ESP Today. Journal of English for Specific Purposes at Tertiary Level, 6, 25-43.

Ammon, U. & McConnell, G. (2002). English as an academic language in Europe: A survey of its use in teaching. (Duisburger Arbeiten zur Sprach- und Kulturwissenschaft 48). Peter Lang.

Bocanegra-Valle, A. (2015). La competencia intercultural en los manuales de texto con fines específicos a través de la evaluación de sus indicadores y niveles de dominio. Cuadernos de Filología Francesa, 26, 29-43.

Bruthiaux, P. (2003). Squaring the circles: Issues in modeling English worldwide. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 13(2) , 159-178.

Byram, M., B. Gribkova & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the Intercultural Dimension in Language Teaching. A Practical Introduction for Teachers. Council of Europe.

Cenoz, J. & Valencia, J. F. (1996). Las peticiones: una comparación entre hablantes europeos y americanos. In J. Cenoz, J. & J. F. Valencia. (Eds.). La competencia pragmática: elementos lingüísticos y psicosociales (pp. 225-238). Servicio Editorial de la Universidad del País Vasco.

Coleman, J. (2006). English–medium teaching in European higher education. Language Teaching, 39, 1-14.

Coleman, H. (2011). Developing countries and the English language: Rhetoric, risks, roles and recommendations. In H. Coleman (Ed.). Dreams and realities: Developing countries and the English language (pp. 9-22). British Council.

Council of Europe (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge University Press.

Coperías-Aguilar, M. J. (2010). Intercultural communicative competence as a tool for autonomous learning. Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses, 61, 87-98.

Council of Europe (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge University Press. http://www.coe.int or http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/CADRE_EN.asp

Council of Europe (2014). Developing intercultural competence through education. Council of Europe Pestalozzi Series, No. 3. Council of Europe Publishing.

De Bartolo, A. M. (2019). A Preliminary Exploration of Teachers’ Attitudes towards Intercultural Communication through ELF. EL.LE, 8(3), 611-634. DOI 10.30687/ELLE/2280-6792/2019/03/006.

Doiz, A., Lasagabaster, D. & Sierra, J. M. (Eds.). (2013). English-Medium Instruction at Universities. Global Challenges. Multilingual Matters.

Egron-Polak, E. & Ross, H. (2010). Internationalization of Higher Education: Global Trends, Regional Perspectives – IAU 3rd Global Survey Report. International Association of Universities.

European Commission (2012). Special Eurobarometer 386: Europeans and languages – a report. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_386_en.pdf

Ferguson, C. A. (1981). Foreword to the First Edition, in Kachru, B. (Ed.) (1996). The Other Tongue. English across Cultures (pp.xiii-xvii). Oxford University Press, 2nd edn.

Fernández-Agüero, M. & Garrote, M. (2019). ‘It’s not my intercultural competence, it’s me.’ The intercultural identity of prospective foreign language teachers. Educar, 55(1), 159-182.

Franco-Aixelá, J. (1996). Culture-specific items in translation. In R. Álvarez & M. C-A. Vidal (Eds.). Translation, power, subversion (pp. 52-78). Multilingual Matters.

Gómez-Rodríguez, L. F. (2015). The cultural content in EFL textbooks and what teachers need to do about it. Profile: Issues in teachers’ professional development, 17(2), 167-187. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.44272

Kling, J. (2019). TIRF language education in review: English as a medium of instruction. TIRF & Laureate International Universities.

Kachru, B. B. (1985). Standards, Codification and Sociolinguistic Realism: the English Language in the Outer Circle. In R. Quirk & H. G. Widdowson (Eds.). English in the World: Teaching and Learning the Language and Literatures (pp. 11-30). Cambridge University Press.

Kachru, B. B. (Ed.). (1996). The Other Tongue. English across Cultures. Oxford University Press. 2nd edn.

Kramsch, C. (2014). Language and Culture in Second Language Learning. In F. Sharifian (Ed.). The Routledge Handbook of Language and Culture (pp. 403-416). Routledge.

Lasagabaster, D. & Doiz, A. (2021). Introduction: Foregrounding language Issues in English-Medium Instructions Courses. In D. Lasagabaster & A. Doiz (Eds.). Language Use in English-Medium Instruction at University. International Perspectives on Teacher Practice (pp. 1-8). Routledge.

Lussier, D. (2007). Theoretical bases of a conceptual framework with reference to intercultural communicative competence, Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(3), 309 –332.

Macaro, E. (2018). English Medium Instruction. Oxford University Press.

Moran, P. (2001). Teaching Culture. Heinle.

Pavón-Vázquez, V. & Ellison, M. (2021). Implementing EMI in higher education: language use, language research and professional development. In D. Lasagabaster & A. Doiz (Eds.). Language Use in English-Medium Instruction at University. International Perspectives on Teacher Practice (pp. 193-207). Routledge.

Reid, E. (2015). Techniques developing intercultural communicative competences in English language lessons. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 186, 939-943.

Saarinen, T. & Nikula, T. (2013). Implicit policy, invisible language: Policies and practices of international degree programmes in Finnish higher education. In A. Doiz, D. Lasagabaster & J. M. Sierra (Eds.). English-Medium Instruction at Universities. Global Challenges (pp. 131-150). Multilingual Matters.

Schmidt-Unterberger, B. (2018). The English-medium paradigm: a conceptualisation of English-medium teaching in higher education. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(5), 527-539.

Shohamy, E. (2013). A critical perspective on the use of English as a Medium of Instruction at Universities. In A. Doiz, D. Lasagabaster & J. M. Sierra (Eds.). English-Medium Instruction at Universities. Global Challenges (pp. 196-210). Multilingual Matters.

Tamtam, A. G., Gallagher, F., Olabi, A. G. & Naher, S. (2012). A comparative study of the implementation of EMI in Europe, Asia and Africa. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 47, 1417 – 1425.

Vu, N. & Burns, A. (2014). English as a Medium of Instruction: Challenges for Vietnamese Tertiary Lecturers. The Journal of ASIA TEFL, 11(3), 1-31.

Wen, Q. (2016). Teaching culture(s) in English as a lingua franca in Asia: Dilemma and solution, Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 5(1), 155-177. DOI:10.1515/jelf-2016-0008.

Wilkinson, R. (2013). English-medium instruction at universities: Global challenges. Multilingual Matters, 3-24.

Received: 3 September 2021

Accepted: 7 October 2021

Notes

i This implies not only the attraction of international students, but being listed in the world’s three most prestigious university rankings: the QS World University Ranking (QS WUR), the Times Higher Education World University Ranking and the Shanghai Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU).

ii According to the 250 Master’s degrees supplement issued by the newspaper El Mundo each year, the Teacher Training for Compulsory and Upper Secondary Education, Vocational Training and Foreign Language Teaching (Máster Universitario en Formación del Profesorado de Enseñanza Secundaria Obligatoria, Bachillerato, Formación Profesional y Enseñanza de idiomas) is among the five best Masters in Spain in its field in its 2020 edition, being the third (out of five) in the Education area. (www.elmundo.es/) (consulted June 25th, 2021).