4. RESULTS

A total of 55 examples were retrieved from the corpora, the majority being cases from written texts drawn from the Internet. Of note, most examples were found in the comments sections of blogs or in posts on forums. Despite the written form of such examples, computer-mediated communication has been shown to bear certain similarities with oral conversation (Herring, 2010); for example, there is typically limited planning time, as in speech production, which favors immediacy and spontaneity and hence leads to a greater use of the colloquial register. In this sense, our data suggests that the retrospective infinitive construction in Spanish is marked as being notably present in oral and informal discourse.

Turning to the examples extracted from colloquial conversations, most of the examples were from conversations occurring in harmonic situations (14 cases) rather than broadly conflictive ones (3 cases). At first sight this appears to run contrary to our initial hypothesis, which assumed the reproachative nature of the construction. However, in addressing the data from a qualitative point of view, we observed that some discrepancies arise within harmonic conversations which can explain the presence of haber + past participle. In other cases, contextual parameters may deactivate or mitigate the potential hostility of the construction (see section 4.3.1.).

Table 2. Frequency of haber + past participle

|

Absolute results |

Relative results

(presence of haber + past participle per 100,000 words) |

Colloquial conversation, harmonic situations |

14 |

1.75 |

Colloquial conversation, conflictive situations |

3 |

8.33 |

Written texts from the Internet |

38 |

- |

4.1. Characterization of structure

There are six traits that allow us to characterize this structure further: 1) the need for it to appear in a reactive turn or to be understood as a reaction; 2) its appellative nature, in that it is addressed to a 2nd person; 3) its present-future orientation although referring to actions performed in the past; 4) its use in expressing counterfactual values; 5) the requirement of agentivity; and 6) its potential to encode a hostile act.

4.1.1. Reactive turn

Haber + past participle cannot be found in discourse-initiating interventions. Unlike imperatives, these constructions require a trigger in order to be uttered. Evidence of this reactive nature is that the construction frequently appears preceded by pues (well, then), as in (4), and indeed in 36.3 % of the examples in our data.

(4)

F: y nosotros casi por un punto/ casi también nos volvemos a marchar a Mallorca// nos volvían a regalar el viaje a Mallorca si comprábamos otra cosa distinta/ yo estaba/ decidida a comprarla (RISAS)

J: no/ no/ porque no puedo ir/ voy a ir a la fábrica↑ y voy a decir↑ oye dame otra semana§

M: § ¡coño!/ pues haberla comprao y vamos nosotros→ MIRA ESTE/ TÚ NO PIENSAS EN LOS DEMÁS/ EGOÍSTA

F: and us almost for (the lack of) a point/ we also almost went back to Majorca// they gave us the trip to Majorca again if we bought something different/ I was/ determined to buy it (LAUGHS)

J: no/ no/ because I can’t go/ I’m going to go to the factory↑ and I’m going to say↑ hey, give me another week§

M: § fuck!/ well you should have bought it and we would go→ LOOK AT YOU/ YOU DON’T THINK ABOUT OTHERS/ (YOU’RE) SELFISH

In the above example, two couples are dining together. F says that she was tempted to buy something from a catalogue because the purchase would have earned her points on a reward program, leading to a free trip to Majorca. Her husband (J) discourages F from doing so because he cannot ask for more days off work. M then jokingly says that they should have bought the product anyway and given the trip to her and her husband, using pues + haber + past participle to express this.

Portolés Lázaro (1989: 131) identifies an adversative value in pues: «If a speaker says p and their interlocutor replies pues q, we must think that q contradicts some conclusion that could somehow be inferred about p, orienting the dialogue towards a different one»5. In this case, the impossibility of J asking for more time off work leads to a conclusion: F and J acted correctly. However, M humorously reprimands J, and then introduces a new conclusion: it would have been possible to buy the product in order to win the trip to Mallorca and then to ask her and her husband to take the trip instead.

Vicente (2013: 52) has argued that this construction does not always appear in a reactive intervention. He proposes that its reactive character must be understood as a tendency, since it can also be found in an initiative position, as in the following example, which he himself gives.

(5)

Scenario: during a soccer match, two players break the offside trap and are left two-on-one against the opposing goalkeeper. Player A is carrying the ball; it is obvious to everyone that if he passes it to Player B, then B will be able to score unopposed. Instead of doing so, A attempts to dribble the goalkeeper and ends up ruining the scoring chance. Enraged, B shouts at him:

¡Habérmela pasado, joder!

«You should have passed me the ball, dammit!»

Strictly speaking, there is not a prior verbal intervention that makes it possible to claim that B’s utterance is reactive, in a similar way to there being no previous intervention when someone says «thank you» to a person who has opened the door for them. However, neither of these two utterances would be possible had the previous action (not passing the ball or opening the door) not been performed. Some activities are not structured exclusively by means of verbalization, but are a combination of the actions that participants take and the way in which these relate to objects and the environment (Evans, 2017). In this sense, these examples can indeed be understood as reactions to previous actions, regardless of whether that action is verbal or non-verbal.

Furthermore, due to the eclectic nature of the corpora used in this study, we have found several such examples in written sources. Even in these cases, the reactive value can be confirmed, in that the speakers strive to recall possible previous interventions to which they respond with haber + past participle.

4.1.2. Prototypically addressed to a 2nd person

Given its directive nature, the structure is usually addressed to the person to whom the 2nd speaker is talking (see examples 3 and 4 above). However, Biezma (2010: 5) provides an example where the referent seems to be a non-present 3rd person. We have found similar examples in the corpora, as (6).

(6)

Muchos profesores tienen miedo al cierre de facultades científicas, pues haberlo pensado antes: no se quedan los mejores, no enseñan los mejores

Many professors are afraid of the closure of science faculties, then they/you should have thought about it before: the best do not stay, the best do not teach

From a grammatical point of view, this case is a reaction to a non-present 3rd person where haber + past participle allows the speaker to show dissatisfaction with the attitude or conduct of that 3rd person. However, from a discursive perspective, such cases can also be understood as a reframing of the situation, with the speakers expressing what they might have said to the addressee had they been present. The reference to a prior discourse or action performed by the professors allows for a shift in the discursive parameters, bringing them closer to the speaker at an enunciative level. In this sense, the infinitive is uttered as if the addressee were indeed present. Moreover, this example includes an element which endorses the use of haber + past participle as part of direct speech, such as the presence of the reactive and counter argumentative discourse marker pues. However, this marker is not always present, especially in oral discourse, where direct speech can be conveyed through the use of prosodic features (Estellés Arguedas, 2015).

In other cases, this polyphonic interpretation arises though the use of quotative devices, such as the quotative que or conditional clauses (7). Examples such as the following represent 13% of the occurrences in our corpora.

(7)

A los conhijos les encanta que juegues con sus hijos porque básicamente se los quitan de encima un rato. Si luego se van sobreexcitados, no habermelo dejado. Encima que te los entretengo, tengo que controlarme, no sea que les excite mucho!! Anda a cagar!

Parents love it when you play with their children because it basically gives them a break for a while. But if the children go home overexcited later, you shouldn’t have let them stay with me. On top of that, I entertain the children and I have to control myself so as not to excite them too much! Shit!

The retrospective imperative constitutes the apodosis, while the protasis includes the reported speech or situation to which the haber + past participle is a reaction. In terms of our collection criteria, these infinitives are not syntactically independent, but rather interdependent6. Another example (ad hoc in this case) is provided by Vicente (2013); in contrast to the previous examples, there is a 3rd-person singular pronoun, which makes it difficult to apply an interpretation involving reframing.

(8)

A: Andrés se queja de que la tortilla que has hecho no sabe bien

B: ¡Pues haberla hecho él!

A: Andrés is complaining that the omelet you cooked doesn’t taste good.

B: He should have cooked it himself, then!

We did not find examples like this in the present corpora. As an alternative, we informally asked native peninsular Spanish speakers – some of whom had studied Spanish Linguistics and others not – if they would say or had heard the structure presented in (8). We found some variation as to the degree of acceptance within these two groups of informants, which might well be seen as a sign that the prototypical use of haber + past participle is to address a 2nd person. Nevertheless, more research needs to be done towards establishing stronger arguments in support of such a claim.

4.1.3. Referring to the past but future-oriented

Linguistic devices similar to the past infinitive can be found in other languages, such as Dutch (Duinhoven, 1995; Van Olmen, 2017), where a verbal form of the past is used to talk about what should have happened. In Spanish, despite the reference to the past being marked through the aspect of the past participle, in 25% of the cases that we analyzed this construction is followed by adverbs and temporal phrases that highlight this reference to the past, such as antes, a su debido tiempo, cuando tocaba, cuando estabas a tiempo (before, in due time, when it was time, when you still have time), among others.

This feature entails a paradox in that the speaker uses a past form to command or admonish, yet these actions are present or future-oriented. In such cases, the future orientation is not conceptualized as something the addressee should do in the future, but something they should have done to achieve a different outcome in the future of that past. It also prompts the addressee to reflect on what they have done and invites them to acknowledge the error of their actions and to recognize the consequences (Van Olmen, 2017).

4.1.4. Expressing counterfactual values

The structure of the enunciation, uttered in the present, in fact refers to a point in the past where a dispreferred action has taken place «and then returns (to) a set of possible worlds lying on the future of that past point» (Vicente, 2013: 15). To illustrate this counterfactual value, we will rephrase example (3a) as if A had paid her taxes.

(9)

A: los medicamentos a mí me los pagan

B: # ¡haber cotizado más!

A: I get my medicines for free

B: # you should have paid more taxes!

Formulated in this way, B’s intervention is pragmatically odd, since A has acted as expected in the past to get her medicine free through the social security system. In other words, the counterfactual value has been deactivated and thus the use of haber + past participle does not work.

4.1.5. The requirement of agentivity

Regarding the directive value of this structure, it is necessary that the addressee to whom the message is addressed has the capacity to carry out the required action. If we consider example (7) again, we can see that the speaker’s utterance is felicitous because the parents, in the past, were in a position to choose whether or not to stay with their child, or this is at least what the speaker believes to be true.

Although less frequent in our data, we have retrieved similar examples where the power of the addressee to perform an action, and thus to be held responsible for the undesired present situation that they are experiencing, is limited. This can be seen in (10) with the verb nacer (‘to be born’). A family is talking about an appropriate time for A to leave the family home. B, an older relative of A’s, has previously stated that he bought his flat when he was 21 years old and explained the effort involved in leaving his parents’ house. A then explains that nowadays it is difficult for someone in his position to become independent in this way, adding that his relatives can achieve this independence for him by giving him an apartment.

(10)

A: hombre/ si me pones un piso↑

B: no yo le puedo poner bien/ yo pongo lo mismo que me han puesto a mí/ lo mismo que me han puesto a mí

C: claaro

A: (RISAS) (…) a Ainhoa mira le han puesto un pisoo (…)

C: aah pues haber nacido- ¡haber nacido de Lidia!↑! no te jode↑

A: Well, if you give me an apartment↑

B: No, I can’t do that. I can only give you what I was given

C: Right

A: (laughs) (…) Look, Ainhoa, she got an apartment (…)

C: Ah, well, you should have been born to Lidia!↑ Fuck!↑

During the interaction, A playfully claims that the parents of an acquaintance (Ainhoa) bought her a flat, implying that to give someone property as a gift is not so extraordinary, and maybe the interlocutors here could do the same for him. An older relative (C) replies that in order to get a flat for free he should have been born as the son of Ainhoa’s mother (Lidia). Clearly, A’s ability to have performed such an action in the past is nil, hence a humorous interpretation is activated.

4.1.6. Potential hostility

It seems that retrospective imperatives are prone to display a certain degree of hostility. In fact, Biezma (2010: 7) qualifies them as «pretty rude» in that they carry a sense of obviousness. Besides the fact that making someone aware of the error in their actions is a potential threat to the addressee’s face, from a discursive point of view we can also perceive elements that signal potential hostility. In our data, we have observed that swear words, pejorative address forms and appellative forms often occur adjacent to the past infinitive, as well as face-threatening acts expressing counterfactivity.

Table 3. Pejorative adjacent words close to the past infinitive

Pejorative forms of address, appellative forms and swearwords |

so bobo, hijo, tonto de capirote, patojo, tú, guapo, coño |

12/55

(21.8%) |

FTAs (face-threatening acts) expressing counterfactivity |

te jodes (screw you), te aguantas (suck it up), ¡muérete! (go to hell), se siente (ironically, ‘too bad’), perdona (ironically, ‘pardon me’), etc. |

13/55

(23.6%) |

Does this mean that the use of this structure necessarily implies rudeness? The answer is no, but there is a tendency to display some hostility. The use of haber + past participle can be found in situations where speakers do not use it in a negative way, as illustrated in (11).

(11)

- Dime, ¿desde cuándo estás en el oficio?

- Desde ayer mismo.

- Pues haberlo dicho. Eso se merece un trago, muchacho.

- Tell me, how long have you been in the position?

- Since yesterday.

- Well, you should have said it. That deserves a drink, boy.

The first speaker discovers that his interlocutor has found a job and wants to celebrate it. In this context, haberlo dicho/you should have said it can hardly be considered rude, in that the speaker’s intention to celebrate the addressee’s good news is clear. However, what is inherent to the construction (no matter if it is in a harmonic interaction or oriented to a good outcome) is that the speaker who utters the past infinitive shows some dissatisfaction about the addressee’s actions in the past, and in doing so makes the addressee responsible for his actions that led to the present undesired situation. According to Vicente (2013: 19), the degree of perceived rudeness or hostility will depend on various factors, including the meaning of the retrospective imperative, the extent to which the speaker is dissatisfied, and the context, among others.

4.2. Retrospective imperative: a form of reproach?

So far, we have characterized the construction haber + past participle based on empirical data drawn from a number of corpora. We will now turn to our second research question, the aim of which is to determine whether these infinitives behave like a specialized form of reproach. It should be noted that some authors (Biezma, 2010; Bosque, 1980; Van Olmen, 2017; Vicente, 2013) have claimed that the construction is indeed used to express a reproach. However, we believe that some reflection is needed regarding the traits that have been cited as defining the (claimed) reproach here, as well as on the way that such reproaches are realized in real examples. Let us take the following example, from a conversation between a group of friends talking about the purchase of a computer, in which haber + past participle is used as a reproach.

(12)

C: ¿¡y por qué no te has comprao un- un Pecé!?

A: ¡coño! cállate ya↓ hombre/ porque es el único que conozco

C: [pero ese no es el mejor]

B: [pero ya te digo/ bu- haber co- bo- consultao a un profesional ¡coño! ¡me cagüen la puta!§

A: § si es un profesional el que yo tengo

B: ¿¡y yo qué te crees que hago↓ nano↑ donde trabajo!?

C: and why haven’t you bought a- a PC!?

A: fuck! shut up already ↓ dude / because it's the only one I know

C: [but that’s not the best]

B: [but I’m telling you/ bu-] you should have co- bo- asked a professional, fuck! bloody hell!§

A: § but the one I have is a professional

B: and what do you think I do↓ bro↑ where do I work!?

First, prior to making a reproach, a speaker must perceive a contradiction in the interlocutor’s words, actions or thoughts (Burguera Serra, 2010; Plantin, 2005). Once the contradiction is identified, the speaker reacts to it by expressing their disapproval. A discursive consequence of this sequence of actions is that reproaches are not only reactive (they require previous activity, whether verbal or non-verbal) but are also usually initiative; when a reproach is uttered, the speaker expects a reaction, preferably a reflection on the addressee’s rights and duties and/or a change in the present or future course of action. For this reason reproaches are situated on the past-present or past-future axis (Burguera Serra, 2010: 405; Van Olmen, 2017). In the example here, B notes a contradiction in A’s behavior: A has purchased a Macintosh instead of a PC because he is not a computer expert; from the perspective of B (an expert) a PC would have been the better option. The actions discussed occurred in the past, but have consequences in the present (A has not chosen wisely).

Reproaches are addressee-oriented, irrespective of whether the addressee is present or not. The addressee is being judged and/or criticized by the speaker, who considers that their interlocutor is responsible for the present bad situation and seeks to provoke a reaction. This reactive-initiative nature, plus the feeling of being judged, leads to reproaches tending to escalate into verbal conflict (Albelda Marco, 2022: 23). As a consequence, reproaches threaten the face of participants and are usually categorized as instances of impoliteness (Burguera Serra, 2010; Ilie, 1994). In example (12), B addresses A aggressively, judging him to have been responsible for a bad choice (buying a Macintosh instead of a PC). A senses this attack and feels the need to reply with a justification of his actions.

In terms of participants’ rights, when a reproach is uttered, the speaker feels morally and deontically entitled to condemn an action and to incite the interlocutor to acknowledge their error and either to emend the error or to recognize it as such. Thus, the speaker projects a deontic and socio-functional asymmetry on the addressee (Stevanovic, 2018; Stivers, 2008); an epistemic asymmetry (García Ramón, 2018; Heritage, 2012) also arises, in that the reproach is conceived as a reminder of the addressee’s duty to act in the right way. Returning to our example, B not only feels entitled to criticize A’s purchase, but also presents himself as expert in the matter, as can be inferred from B’s last intervention.

Finally, reproaches are eminently directive. However, like speech acts such as apologies and justifications, they also present features of expressive illocutionary force, and hence can be understood as acts with a hybrid illocutive force in which the directive and the expressive force combine (Albelda Marco, 2022). The expressive value stems from the negative judgement that a speaker makes about an addressee’s past actions (like buying a Macintosh instead of a PC). From the speaker’s point of view, an expectation of what should have been done is not met, and this grants them the right to express their dissatisfaction. As for the directive value, we have already described the desire to provoke a reaction in the interlocutor.

From what we have seen, then, the characteristics of the construction and the traits that define the act of reproaching have a lot in common. Hence it seems safe to say that this construction has a high degree of specialization in conveying reproach. However, our data also reveal that it is not every case in which haber + past participle appears in a statement that it can be interpreted as reproachful. Likewise, since reproaches are acts of a reactive-initiative nature, it is also necessary to analyze replies to these statements to better understand the way in which the construction is used, and how it can be interpreted from a discursive point of view.

4.3. Discursive patterns

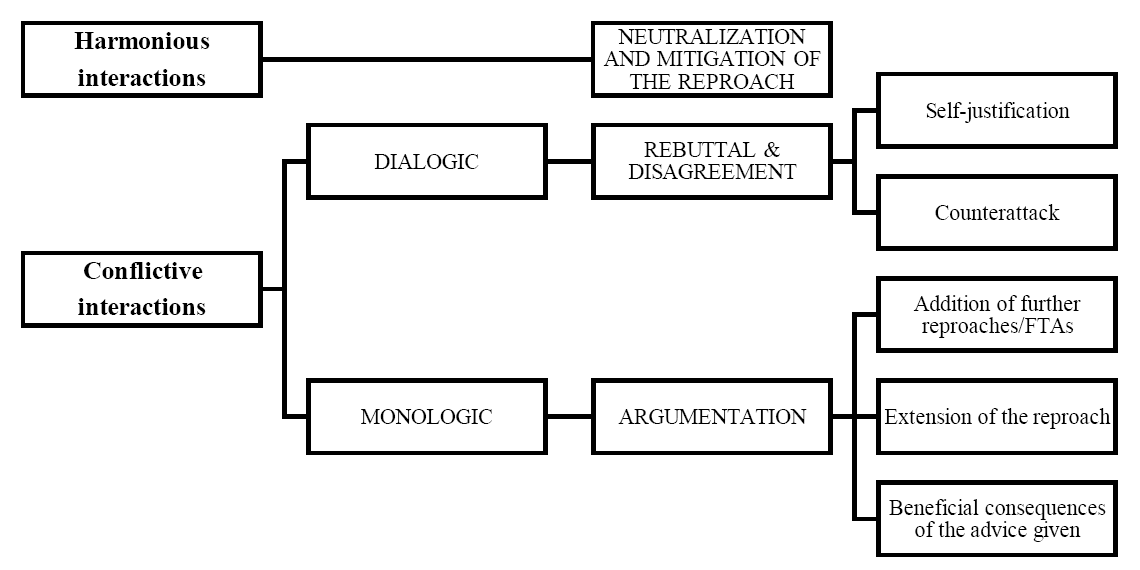

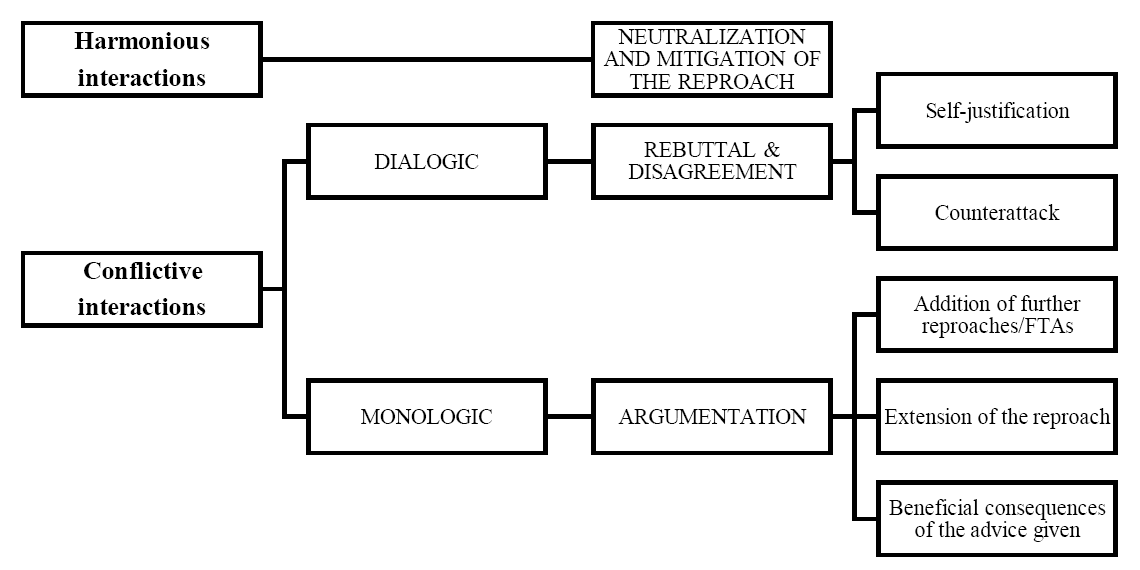

In this section we will address the issue of discursive patterns, understood as a «recurring practice in the configuration of discourse that, without reaching a fixed form, constitutes a frequent routine when arranging informative materials»7 (Taranilla, 2015: 260). To this end, attention must be paid not only to the form itself and the linguistic devices and structures that usually appear with the past infinitive, as discussed above in section 4.1., but also to the way in which the infinitive is used in the construction of discourse and in successive interventions. From this perspective, it will be possible to identify patterns of usage, as summarized in Figure 1, which we will address in more detail in what follows.

Figure 1. Discursive patterns in harmonic and conflictive interactions

4.3.1. Neutralization and mitigation of the reproach

The neutralization of a reproach occurs when some of the characteristics described in the previous sections are not present. For example, in (16) speaker C recriminates her younger relative for not having been born to a different person (haber nacido de Lidia/ you should have been born to Lidia). Since the requirement of agentivity is not met, the addressee cannot be held responsible for their past actions and thus the reproach is neutralized.

In other cases, all the characteristics are present, but there may also be other elements (such as ironic and humorous values or pseudo-impoliteness) that lead to a less menacing interpretation. Consequently, the reproach can be mitigated or even neutralized, as illustrated in example (4), here shortened and renumbered as (13).

(13)

M: § ¡coño!/ pues haberla comprao y vamos nosotros→ MIRA ESTE/ TÚ NO PIENSAS EN LOS DEMÁS/ EGOÍSTA

M: § Fuck!/ Well, you should have bought it and we would go→ LOOK AT YOU/ YOU DON'T THINK ABOUT OTHERS/ (YOU’RE) SELFISH

In (19), M’s intervention may seem to be a reproach, in that she scolds her friend for not having made a purchase that would have resulted in getting a free trip to Majorca which in turn she could have given to the speaker (M) and her husband. She even brands her interlocutor as selfish for not having done so. This exaggeration, and the fact that M’s friends are not responsible for organizing M’s holidays, triggers a rather humorous or ironic interpretation of the utterance. However, can we be sure that M is in fact satisfied with her friend’s decision, and that she does not expect to be consulted if a similar opportunity arises in the future? In other words, is she appealing for the reconsideration of a past action in order to encourage a reflection on it, or to encourage a different way of acting in the future? In the following interventions M continues with the joke until J explains that the item they had to buy was too expensive. It seems that in such cases it is not absolutely clear that the reproach is neutralized, but the harmonic context favors a diluted and playful interpretation.

4.3.2. Rebuttal and disagreement

When haber + past participle is uttered in conflictive dialogic interactions, the addressee can respond in two ways. First, they might agree with the speaker that the action in the past was not performed and try to justify their actions and make amends in some way. This is what happens in (14), where a couple interact while driving a car.

(14)

Woman: o sea lo que es un horror es no poder parar tanto/ que lo tenías tú ya pensado

Man: ¿qué pensado?

W: si tú sabes que has parado con tus padres en ese sitio siempre digo

M: [hombre claro pero a tomarme] algo

W: [pues si ya sabes que no hay nada]/ pues es que- pues es que si tenías que comprar ahí algo y no había ni para sentarse/ pues tú ya conocías el sitio pues hijo haberlo calculado↑ / y dices pues ya paramos/ pues no/ no paramos

M: bueno pero no nos paramos/ pu- pues ahora estoy buscando tu área picnic

Woman: I mean, what is a nightmare is not being able to stop as much as we’d like. You’d already thought it

Man: think what?

W: if you know that you’ve stopped with your parents always at that place, I say

M: [of course, but to get something to drink]

W: [well, if you already know there’s nothing]/ it’s just that... if you had to buy something there and there wasn’t even a place to sit/ since you already knew the place, then, honey, you should have calculated it/ and you say «we’ll stop»/ «or no / we’re not stopping»

M: well, but we didn’t stop/ so now I’m looking for your picnic area

In this example, a woman reproaches her husband for not having calculated that they are not able to stop at a service area on the highway because there are no shops or picnic areas. The husband’s reply serves as a defensive strategy, agreeing with his wife (no nos paramos/we didn’t stop) and justifying himself, as he is now actively looking for a good picnic spot for her.

The following example illustrates a case of a counterattack. A couple are discussing picking up their children from school by car.

(15)

Woman: claro/ es que además es agotador yo lo del coche las sillas y no sé/ o sea es que eso es

Man: sí/ a ti se te ve superagotada María (irónicamente)/ que es mi guerra de todos los días/ o sea [qué me estás contando]

W: [oye Eduardo]

M: que [tú los recoges] dos [días a la semana]

W: [pues a mi] [las veces que he] ido y cuando he ido con Manuel con todos ↑… haber cogido los coches↑/guapoo↑

M: yo los llevo todos los días y los recojo el resto/ que es mi- mi rutina de las mañanas ¿eh?

Woman: of course, besides it’s exhausting for me to deal with the car, the seats, and I don’t know. It’s just that is...

Man: yes, María, you look really tired (ironically). It’s my daily battle. I mean, what are you telling me?

W: Hey, Eduardo...

M: You pick them up two days a week.

W: Well, the times I’ve gone and when I went with Manuel with everyone... you should have taken the cars, darling!

M: I take them everyday and pick them up the rest of the time. It’s my morning routine, right?

The infinitive is used here by the wife (Haber cogido los coches, guapo/You should have taken the cars, darling!). In the following intervention, the husband replies using disagreement, which can be understood as another reproach: I take the kids every day and I pick them up the rest, it’s my daily routine, uh? In our data, this value of disagreement and counterattack is the most frequent in conflictive conversations.

4.3.3. Argumentation

In monologic contexts, we can find cases where the infinitive appears directed to a non-present interlocutor that the speaker invokes or recalls from a past or hypothetical intervention or situation. The interlocutor is not present, and thus cannot make an immediate response, and this allows the speaker to develop their line of argument. In our data, we have observed three ways that this argumentation develops: through the addition of further reproaches or FTAs, an extension of the reproach, and the expression of beneficial consequences of the advice given. Example (16) illustrates the first of these.

(16)

En mi caso (...) he encontrado una gran tabla de salvación en la Infidelidad más impertinente, descarada y absoluta... ¡Ah, se siente! Lo siento, amada. No haber engordado. No haberte traído a mamá a casa. No haberte apuntado al AMPA del colegio. No haberte teñido color mesilla de noche. A mí me ha cambiado el tiempo y tú has querido cambiar el tiempo. Y no es lo mismo, amor.

In my case (…) I’ve found my lifeline in the most impertinent, shameless and absolute infidelity… Tough! I’m sorry, darling! You shouldn’t have gained weight. You shouldn’t have brought your mom home. You shouldn’t have signed up for the school’s parent association. You shouldn’t have dyed your hair the color of the bedside table. Time has changed me and you have wanted to change the time. And it is not the same, love.

Despite the apologies and the affectionate forms of address, new reproaches compound and magnify the (hypothetical) reprimand that the speaker is making to his not-so-beloved wife for not taking good care of her appearance, among other things. As a result, the threat to the addressee’s face is heightened by the accumulation of reproaches.

Another way of developing the argument is to extend a reproach. In the following example, the speaker is posting on a forum a response to someone who complained in a previous post about spending too much time taking care of their child.

(17)

Lo siento, haberlo pensado antes de tener hijos. Él no tiene la culpa de que te canses jugando, mirándole en el tobogán y columpiándole. Si te pones nerviosa porque el niño se despelota, es tu puto problema, a él le parece de lo más interesante.

I’m sorry, you should have thought it before having children. It's not his fault that you get tired playing, watching him on the slide and swinging him. If you get nervous because the child gets naked it’s your fucking problem, he finds it very interesting.

As in the previous example, the use of an apology before the reproach is insincere since what follows conveys no empathy for the parent’s situation. Moreover, the next utterances are an expansion of what the speaker has implied (haberlo pensado antes/you should have thought it before) because it presents the behavior of the child as something normal that the parent should have expected (and therefore accepted) when they decided to have a child.

The final possible pattern differs from the previous ones in that it makes explicit the positive consequences that would have been achieved if the addressee had acted differently in the past.

(18)

Yo tengo la suerte de tener un trabajo cualificado donde me pagan bien por lo que hago y eso me permite tener ocio y vivir bien. Haber estudiado hombre y así vivirías mejor.

I’m lucky to have a qualified job where I get paid for what I do and that allows me to have leisure time and live well. You should have studied, mate, and then you would live better.

The interlocutor is reproached for not having studied, because had he done so he would now have more leisure time and a better quality of life. After uttering the infinitive, the beneficial consequences of having followed the advice conveyed by the reproach are expressed.