Cultura, lenguaje y representación / Culture, Language and Representation

Llorens-Simón, Eva María (2024): Exploring the Metaphorical Language of Menstruation. Health, Hygiene or Camouflage? Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación, Vol. XXXIV, 83-106

ISSN 1697-7750 · E-ISSN 2340-4981

DOI: https://doi.org/10.6035/clr.7878

Universitat Jaume I

Exploring the Metaphorical Language of Menstruation. Health, Hygiene or Camouflage?

Explorando el lenguaje metafórico sobre la menstruación. ¿Salud, higiene o camuflaje?

Artículo recibido el / Article received: 2024-01-16

Artículo aceptado el / Article accepted: 2024-03-24

Abstract: This article is centred on a corpus-based methodology and approach to delve into the metaphoric language surrounding menstruation. Its primary goal is to illuminate prevalent figurative expressions and their implications on societal perceptions concerning women’s health and menstruation. Observing a relevant and representative corpus on the topic, our findings underscore a notable thematic concentration on health and hygiene-related metaphors. However, most of them, despite their science-centric nature, carry a significantly negative undertone, perpetuating stereotypes that cast menstruation as an unfavourable and stigmatised experience. This study positions menstruation within a broader social context, revealing a pervasive inclination to camouflage this natural phenomenon. Despite being a fundamental aspect of women’s lives, metaphors often portray menstruation as an adverse event, a dark circumstance, or a longstanding taboo, transcending cultural and historical boundaries. By shedding light on these linguistic nuances, this research contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the language used to discuss menstruation. Through this exploration and evaluation, we advocate for a shift towards inclusive and empathetic discourse surrounding women’s health discourse.

Key words: biomedical discourse analysis, gender-sensitive terminology, corpus-based analysis, metaphors, women’s health

Resumen: Este artículo se basa en el análisis de corpus como metodología y enfoque para profundizar en el lenguaje metafórico referido a la menstruación. Su principal objetivo es mostrar expresiones figuradas predominantes en este tipo de discurso y analizar sus implicaciones en las percepciones sociales sobre salud femenina y menstruación. Con la observación de un corpus relevante y representativo acerca del tema, nuestros resultados ponen de relieve una notable concentración temática en las metáforas relacionadas con la salud y la higiene. Sin embargo, la mayoría de ellas, a pesar de su carácter científico, conllevan un matiz eminentemente negativo, por lo que contribuyen a la consolidación de estereotipos que presentan la menstruación como una experiencia desfavorable y estigmatizada. De hecho, este estudio engloba la menstruación en un contexto social más amplio y revela una tendencia generalizada a camuflar este fenómeno natural. A pesar de ser un aspecto fundamental de la vida de las mujeres, las metáforas suelen retratar la menstruación como un acontecimiento adverso, una circunstancia oscura o un tabú persistente a lo largo del tiempo que traspasa las fronteras culturales e históricas. Al poner de manifiesto estos matices lingüísticos, este trabajo de investigación permite comprender con mayor rigor cuál es la trascendencia del lenguaje utilizado para hablar de la menstruación. A partir de esta labor de análisis y evaluación, abogamos por un cambio hacia un discurso inclusivo y empático en torno al lenguaje sobre la salud de la mujer.

Palabras clave: análisis del discurso biomédico, terminología sensible al género, análisis basado en corpus, metáforas, salud en la mujer

1. INTRODUCTION

The historical treatment of women’s health phenomena has, regrettably, been marred by collective norms that often render natural processes as illnesses or stigmatising syndromes to be hidden from the public eye (Barona, 2023; Wood, 2020; Ussher and Perz, 2014). This overarching tendency is especially evident in the discourse surrounding menstruation, a fundamental aspect of women’s lives. Instead of embracing menstruation as a natural and positive occurrence, it has traditionally been relegated to the shadows, obscured by cultural taboos, and darkened with an inclination to view it through a lens of fault or handicap (Blázquez Rodríguez, 2023; Gottlieb, 2020; Jackson and Falmagne, 2013; Luke, 1997; Idoiaga-Mondragon and Belasko-Txertudi, 2019).

The narrative surrounding menstruation, kept by centuries of cultural influence, extends beyond mere perceptions and has penetrated the medical discourse as well (Blázquez Rodríguez, 2023; Jeoung, 2020). In fact, the language used to describe menstruation both in scientific and general discourse has contributed significantly to the perpetuation of negative stereotypes, portraying this natural process as undesirable and in need of concealment rather than acceptance (Bonilla Campos, 2023; Burrows and Johnson, 2005; Johnston-Robledo and Chrisler, 2020; Newton, 2016; Wood, 2020).

Our specific focus is to unravel the metaphorical language encapsulating menstruation. By employing a corpus-based methodology, we aim to shed light on prevalent figurative expressions and their social implications, transcending the boundaries of negative biases that have clouded the discourse on women’s health.

As we navigate the linguistic landscape surrounding menstruation, our mission extends beyond analysis to action. We strive to challenge the historical discourse that has obscured the natural and positive essence of menstruation. This exploration is not merely an academic endeavour but a call to transform the prevailing narrative, fostering inclusive and empathetic discourse that recognises menstruation as an inherent and fundamental aspect of women’s lives.

In summary, our overarching goal is to exhibit how figurative language contributes to the consolidation of stereotypes and taboo-centred attitudes involving concealment and silence, which were perpetuated within the discourse surrounding menstruation all over history and somewhat validated with scientific and medical discourse seconding them. After a meticulous observation of the corpus, we aim to bring to light ingrained assumptions and biases on menstruation references. With this knowledge, our ultimate purpose is to propose inclusive and gender-sensitive alternatives in the future. Through this multifaceted analysis, we aspire to contribute meaningfully to the ongoing transformation of the narrative, fostering a language that embraces the natural and positive essence of menstruation within the broader female experience.

1.1. Menstruation through the ages. biases in medical discourse

From a scientific perspective, it may be assumed that medical discourse is devoid of stereotypes and biased assumptions (Blázquez Rodríguez, 2023: 133). This belief is particularly rooted in the expectation that specialised language in the medical field is objective, accurate, and respectful, given its significant impact on society and its role in disseminating fair practices (Bobel, 2010; Foucault, 1973; Hyland, 2010; McHugh, 2020; Pao, 2023). Consequently, the recurring metaphors on menstruation in medical language may be initially expected as distant from stereotyped images or stigma, considering the professional overtone attributed to the prototypical discourse of medicine (Bonilla Campos, 2023; Northup, 2020; Pao, 2023; Wilce, 2009; Zeidler, 2013). However, numerous samples of medical and health discourse on menstruation through the ages demonstrate that figurative language referring to this natural process is mainly negative, undesirable, and therefore likely to be camouflaged (Blázquez Rodríguez, 2023; Gottlieb, 2020; Jeoung, 2023; Wood, 2020; Paterson, 2014).

Historically, the perception of menstruation by different doctors and within the medical field has evolved significantly (Barona, 2023: 48). Early medical perspectives often framed menstruation within a context of pathology or imbalance, viewing it as a discharge of toxins or impurities (Gottlieb, 2020; Jackson and Falmagne, 2013; Ussher and Perz, 2014). Ancient Greek and Roman physicians, such as Hippocrates, attributed menstrual symptoms to a supposed excess of "female humours" that needed to be purged from the body (Gómez Sánchez et al., 2012: 375).

During the Middle Ages, menstruation continued to be associated with notions of imbalance and impurity. Some medical practitioners, influenced by prevailing religious and cultural beliefs, regarded menstruation as a consequence of women’s inherent inferiority or as a form of punishment for Eve’s biblical transgressions (Barona, 2023; Gómez Sánchez et al., 2012).

In the 19th century, as medical understanding advanced, there was a gradual shift toward more scientific interpretations. However, many doctors still viewed menstruation through the optics of pathology. Menstrual disorders were often pathologized, and prevailing cultural norms influenced the medical discourse, reinforcing negative perceptions (Gómez Sánchez et al., 2012; Jeoung, 2023; Ussher and Perz, 2014).

The early to mid-20th century witnessed increased medicalisation of menstruation. (Ussher and Perz, 2014). Menstrual hygiene products were developed, and medical professionals contributed to the understanding of menstrual cycles (Donat Colomer, 2023; Margaix Fontestad, 2023). Nevertheless, societal taboos persisted, influencing medical discourse and the perception of menstruation as a topic not to be openly discussed (Bobel, 2010; McHugh, 2020; Newton, 2016; Wood, 2020).

In recent decades, there has been a growing acknowledgement within the medical community of the normalcy and importance of menstruation (Blázquez Rodríguez, 2023; Botello Hermosa y Casado Mejía, 2017). Efforts to destigmatise menstrual health (Blázquez Rodríguez, 2023; Hennegan et al., 2021), coupled with advancements in women’s health research, have contributed to a more nuanced understanding of menstruation as a natural and essential aspect of reproductive health (Espejo Martínez et al, 2019). Nevertheless, despite contemporary advancements in medical publications, a considerable portion of images and analogies employed today in reputed medical publications echoes the figurative language and stereotypes that have traditionally enshrouded the discourse on menstruation (Cimino et al, 1994; Jeoung, 2023; Patterson, 2014; Semino, 2011). This perpetuation of age-old linguistic constructs contributes to the endurance of negative connotations and a persistent inclination towards the concealment of menstruation references (Jeoung, 2023; Newton, 2016; Weedon, 1987; Wood, 2020). The traces of these linguistic patterns extend beyond menstruation to encompass the broader spectrum of language concerning women’s health phenomena (Espejo Martínez et al, 2019)

Throughout history, diverse cultural, religious, and social influences have shaped medical perspectives on menstruation, reflecting broader attitudes. The evolution of these perspectives highlights the intersectionality of medical discourse, gender norms, and cultural beliefs surrounding this natural bodily process, which contributes to the persistence of biases, stereotypes, and assumptions in the present discourse (Johnston-Robledo and Chrisler, 2020; McHugh, 2020; Patterson, 2014)

2. HEALTH AND GENDER-SENSITIVE PERSPECTIVES

2.1. DIGITENDER: A research project as a framework

The significance of addressing women’s health issues through a gender-sensitive view has become increasingly prominent in recent years (Espejo-Martínez et al, 2019; Idoiaga-Mondragon and Belasko-Txertudi, 2019; Luke, 1997; WHO, 2022). Responding to this imperative, our project emerged in pursuit of a more equitable society that values gender diversity.

This work is integrated into DIGITENDER, a gender terminology research project (DIGITENDER, TED2021-130040B-C21) that undertakes a comprehensive examination of language within women’s health discourse. This project is dedicated to digitising, processing, and digitally publishing open, multilingual terminology resources, with a specific emphasis on gender perspectives in the digital realm. The integrative objective is to generate an extensive and accessible resource set capable of mitigating gender bias in language usage across diverse digital platforms.

At the heart of the research project is the development of a centralised repository containing gender-sensitive terminology. This repository is envisioned as a practical tool for individuals and organisations committed to fostering inclusive and equitable language practices. Our study involves an in-depth analysis of existing terminology resources, the establishment of a digital infrastructure for data storage and dissemination, and the implementation of a community-driven approach to ensure continuous evolution and enhancement of the resources.

In essence, our project aspires to make meaningful contributions toward fostering a more inclusive and gender-sensitive digital society.

DIGITENDER is also related to the creation of WHealth, an extensive open-access repository of terms, which serves as a fundamental aspect of the above-described initiative. WHealth aims to bring visibility to health problems and issues impacting women, addressing topics such as menstruation, infertility, menopause, and eating disorders. Through this comprehensive resource, the project seeks to empower the public with relevant information, challenging taboos and stereotypes that can contribute to health problems and their assumption as biased or limiting processes.

2.2. Menstruation and gender considerations

The definition given by Oxford Dictionary for menstruation is:

The discharge of blood and fragments of endometrium from the vagina at intervals of about one month in women of childbearing age (see menarche, menopause). Menstruation is that stage of the menstrual cycle during which the endometrium, thickened in readiness to receive a fertilized egg cell (ovum), is shed because fertilization has not occurred. The normal duration of discharge varies from three to seven days (…)

(Oxford Dictionary, 2023)

It is worth observing that this definition does not contain any references indicating that menstruation is an illness, a pathology, or a disease, but it alludes to a stage in a cycle when fecundation has not taken place. Therefore, it is assumed that additional constructs may have been culturally disseminated but not lexically supported or preliminarily prejudiced.

In terms of global health, a statement on menstrual health and rights was included in the 50th session of the Human Rights Council Panel discussion on menstrual hygiene management, human rights, and gender equality (2022). This initiative was relevant in the sense that previous global conferences and events did not consider this step significant, as mentioned on the World Health Organisation website:

Menstrual Health was not on the agenda of the International Conference on the Population and Development or the Millennium Declaration. Nor it is explicitly stated in the Sustainable Development Goals targets for goals 3 (health), 5 (gender equality) or 6 (water and sanitation).

(WHO, 2022)

Additionally, some specific actions are also expressly mentioned in this representative organisation’s publications for a positive approach to be attributed to menstruation:

WHO calls for three actions. Firstly, to recognize and frame menstruation as a health issue, not a hygiene issue – a health issue with physical, psychological, and social dimensions, and one that needs to be addressed in the perspective of a life course – from before menarche to after menopause. Secondly, to recognize that menstrual health means that women and girls and other people who menstruate have access to information and education about it; to the menstrual products they need; water, sanitation, and disposal facilities; to competent and empathic care when needed; to live, study and work in an environment in which menstruation is seen as positive and healthy, not something to be ashamed of; and to fully participate in work and social activities. Thirdly, to ensure that these activities are included in the relevant sectoral work plans and budgets, and their performance is measured […] WHO is also committed to breaking the silence and stigma associated with menstruation and to make schools, health facilities and other workplaces (including WHO’s workplaces), menstruation responsive.

(WHO, 2022)

Given the aforesaid reflections, it is manifested that WHO’s directives align closely with the goals of our research project in promoting gender sensitivity. This organisation emphasises the need to destigmatise menstruation and eliminate negative assumptions. Notably, WHO advocates for comprehensive menstrual health, encompassing access to information, education, menstrual products, water, sanitation, and disposal facilities, as well as empathic care. Importantly, it calls for an environment where menstruation is viewed positively, devoid of shame, enabling individuals to fully participate in various aspects of life. It is conceived, therefore, that language is to be integrated into the positive atmosphere promoted and appealed to by this representative body.

The WHO statement serves as a powerful validation of our project’s objectives, signalling the global recognition of menstruation as a gendered subject that requires dedicated attention. The acknowledgement of menstrual health as a priority by a global institution in 2022 underscores the overdue need for such initiatives and challenges to transform existing societies.

Furthermore, the identification of menstruation as a gender issue (Song et al., 2016: 185) discloses the evident disparity in the cultural and linguistic treatment of non-female reproductive or hormonal processes in terms of neutrality, which entails a stark contrast with the embarrassment, stigma or pathology-based attitudes exhibited toward individuals menstruating. (Espejo Martínez et al., 2019: 206). Hence the need for a gender-sensitive approach and the core of this research work.

By fostering inclusive, respectful, and equitable language after showing linguistic evidence of unfair and impartial conceptions, our project aims to contribute to breaking the silence and destigmatising menstruation, ultimately enhancing equality among individuals preliminarily prejudiced.

2.3. Metaphors and gendered women’s health discourse

The utilisation of metaphors in medical discourse is linguistically substantiated, as referenced in a prior work by Navarro-i-Ferrando (2017). This assertion is grounded in the recognition that metaphors serve a fundamental role in bridging our comprehension of the world with the language employed in scientific contexts (Brown, 2003; Navarro-i-Ferrando, 2017). In our work, the intricate interplay between metaphorical language and medical discourse becomes evident as well, with an essential contribution to shaping our understanding of complex concepts within the realm of women’s health.

The integral role of metaphors in scientific language, particularly in conceptualisation and theory representation, has been underlined by scholars for decades, and more recently by Navarro-i-Ferrando in his article (2017: 164), where he expressly alludes to several authors and experts who agree on the relevance of metaphors in science and medicine (Black, 1962; Gentner and Gentner, 1983; Kuhn, 1993). As referenced by Navarro-i-Ferrando (ibid.) recent in-depth analyses by Brown (2003: 11) and Zeidler (2013: 101) further illuminate the significance of metaphors in scientific discourse. In the field of Medicine, researchers have approached discourse through genre analysis, as stated by Navarro-i-Ferrando (Yanoff, 1988; Salager-Meyer, 1994; Gotti and Salager-Meyer, 2006; Navarro-i-Ferrando, 2017; Wilce, 2009) and terminology studies (Dirckx, 1983; Cimino et al., 1994).

A noteworthy contribution involves the qualitative analysis of specific metaphors within medical discourse (Navarro-i-Ferrando, 2016, 2017; Semino et al., 2004; Semino, 2008, 2011). According to Semino (2011: 130), metaphors exhibit distinct adaptations across genres with varying social scopes, particularly in terms of communicative and conceptual functions. Research in healthcare and illness, influenced by Sontag’s seminal work Illness as Metaphor (1978: 18), often adopts a sociological perspective, exploring metaphor usage in therapy, doctor-patient communication, and healing processes (Demjén and Semino, 2016).

In this case, our corpus study has also contributed significantly by revealing the pervasive nature of metaphors in technical medical texts (Mungra, 2007; Navarro-i-Ferrando, 2017), although not exactly to improve communicative interaction or healing attitudes, but to extend, and somewhat endorse, traditional beliefs and conventions on embarrassment and impurity in menstruation.

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Metaphors, gender, and corpus analysis

The corpus analysis serves as both the methodological approach and the analytical tool for identifying prominent figurative patterns and examining their contextual usage, including gendered nuances and recurrent themes (Timofeeva and Vargas-Sierra, 2015). Specialized software, particularly Sketch Engine (2023), facilitated the compilation, location, and contextual analysis of recurring metaphors. This software enabled not only the quantification and identification of key terms and related metaphors but also the automation of processes preceding the qualitative study of gendered conceptions and usual connotations. Particularly noteworthy functions included the ’Wordlist’ feature for identifying frequent items according to predefined categories and the ’Concordance’ function for displaying frequent keywords in context, facilitating a more nuanced interpretation and evaluation of connotations.

The selection of the corpus source was deliberate and meticulous, taking into account factors such as the recent publication of the monograph that inspired the study, the inclusion of a historical review on menstruation, the predominantly biomedical and scientific discourse, and the expertise of the contributing authors (Leech, 2007). The corpus, compiled via Sketch Engine, is derived from a reputable treatise on menstruation titled «La menstruación: de la ideología al símbolo» (Donat Colomer, 2023), authored by esteemed experts, men and women. It represents an innovative and comprehensive resource for Spanish discourse on menstruation, integrating current knowledge, frequent terminology, new perspectives on biomedical discourse, and authentic scientific language in women’s health.

While biased metaphors and stereotyped images may initially appear concentrated in chapters discussing the historical evolution of menstruation discourse, the qualitative analysis revealed their pervasive presence throughout the corpus. Although adverse and stigmatised patterns are more prevalent in historical references, recurring figurative elements across chapters disclose the persistence of negative associations. The corpus-based study provides statistical confirmation of the gendered analogies and stigmatisation within menstruation discourse, offering a comprehensive and representative sample for analysis (Berber Sardinha, 2002; Bowker and Pearson, 2002; Leech, 2007; Vargas-Sierra, 2012).

The representativeness and value of the corpus stem from its association with a reputable publication, its recent release, its acceptance within the expert community, and the support provided by Sketch Engine. This software enables the identification and display of total frequencies, occurrences, collocates, and contexts based on predefined criteria and categories, facilitating rigorous analysis and interpretation (Baker, 2003; Bowker and Pearson, 2002; Croft, 1991). Following this initial observation, qualitative exploration serves as the next logical step to enhance data interpretation, particularly concerning gendered concepts.

3.2. Figurativeness in the corpus

Our research methodology has been delineated aiming to assess the prevalence of figurative patterns associated with gendered concepts (Fernández Díaz, 2013: 50), which act as influencers of social perceptions within menstruation discourse. We posit that these linguistic elements play a crucial role in shaping cultural stereotypes and biases related to women’s health, portraying menstruation as a pathology, an unhygienic concern, or a concealed process evoking shame (Jeoung, 2023; Newton, 2016; Wood, 2020).

Our investigation initiates with the creation of a specialised ad-hoc corpus (Bowker and Pearson, 2002) in Spanish, consisting of approximately 90,000 words. Despite its modest size and consideration as small (Berber Sardinha, 2002; Vargas-Sierra, 2012), the corpus is strategically tailored to the specialised focus of our research (Leech et al., 1994). As advanced in the section above, text samples are sourced from a credible publication on women’s health, authored by medical professionals and experts (Donat Colomer, 2023), ensuring representativeness according to our study’s objectives (Leech et al., 1994).

The compilation process involved the inclusion of the whole book as a scholarly compendium notable for its up-to-the-minute and extensive coverage of menstruation. This book includes a comprehensive tour, incorporating anthropological, historical, psychological, and biological perspectives along with recommendations on women’s care and details on menstrual alterations, providing a thorough review of its significance both historically and in contemporary contexts. (This compilation was facilitated through the automation capabilities of the Sketch Engine software (2023), optimising data quantification and enhancing research efficiency.

In the initial phase of the corpus analysis, we adopt a quantitative approach, focusing on keywords and expressions, particularly perception nouns and adjectives, given their presence in triggering metaphorical senses (Baker, 2003; Cifuentes Honrubia, 1994; Croft, 1991; Gordon and Lakoff, 1971; Halliday, 1978, 1994; Langacker, 2008). This quantitative assessment provides an empirical measure of the significance and prominence of these elements in the discourse.

Furthermore, to comprehensively understand the conceptual landscape of women’s health discourse on menstruation, we identify and quantify three mental conceptions arising from the quantitative stage: menstruation is a pathology, menstruation is against hygiene, and menstruation is to be camouflaged. Employing these keywords and their synonymous as search prompts, as well as observing the segments surrounding them, we determine the prevalence of metaphorical sequences, exploring not only their frequency but also their emotional transcendence.

This single-minded approach extends our research scope, offering insights into the connotational nuances of recurrent metaphorical sequences within the discourse. It unveils not only the analogies present, but also their positive or negative implications, contributing to a more refined understanding of how metaphors are intertwined with menstruation discourse shaping cultural narratives on women’s health.

Following the quantitative analysis, we progress to qualitative scrutiny, exploring contextual overtones of frequent linguistic patterns. Our objective is to identify specific metaphors and connotations related to menstruation (Timofeeva and Vargas-Sierra, 2015). This qualitative analysis provides insights into the figurative dimensions present in the language related to menstruation across historical periods.

In summary, our corpus analysis methodology leverages the automation capabilities of Sketch Engine to compile and search a specialised corpus. This approach allows us to investigate the frequency, figurativeness, and biased content of language related to menstruation. We assert that frequency indicates linguistic relevance and authenticity, while metaphorical and connotational dimensions reveal the extent of embedded stereotypes and biases.

By employing this methodology, we aim to offer a comprehensive understanding of the metaphorical components within women’s health discourse, shedding light on their societal impact.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results gleaned from our corpus analysis manifest the dominant metaphorical patterns embedded in women’s health discourse, particularly within the realm of menstruation. Our investigation unveils the sociocultural lenses that have influenced the language employed to articulate menstruation women’s experiences across different periods and cultures.

4.1. Metaphorical narratives as sociocultural constructs

Examining the data obtained through Sketch Engine search queries, the frequent use of revealing perception nouns such as pain, change, discomfort, unease, inconvenience, silence, irritability, odour, impurity, dirt, disgust, invisibility, upset, or burning pain contributes to a noticeably biased portrayal of menstruation as an unpleasant process, rather than a natural one. Specifically, out of a total frequency of 1,418 occurrences, these nouns constitute 438 (30.9%). Moreover, the contexts surrounding many other nouns, most of them sense-related references, including vision, quantity, intensity, heat, sensation, image, contact (especially blood contact), dryness, size, colour, perception, texture, and volume, also incorporate predominantly negative notions, resulting in an additional 301 occurrences with disagreeable connotations (see Figure 1).

Table 1. Recurring nouns. Source: Sketch Engine

NOUNS (66 items) / 1418 Total Frequency (F) |

Noun |

F |

Noun |

F |

Noun |

F |

Noun |

F |

1 ciclo |

272 |

14 imagen |

25 |

27 frío |

10 |

40 suciedad |

3 |

2 dolor |

173 |

15 espacio |

24 |

28 sequedad |

10 |

41 lengua |

3 |

3 cambio |

145 |

16 mirada |

24 |

29 tamaño |

10 |

42 asco |

3 |

4 experiencia |

128 |

17 contacto |

19 |

30 silencio |

9 |

43 fragancia |

3 |

5 visión |

52 |

18 luz |

18 |

31 color |

9 |

44 invisibilidad |

3 |

6 cantidad |

51 |

19 ojo |

17 |

32 percepción |

8 |

45 textura |

2 |

7 intensidad |

50 |

20 signo |

16 |

33 incomodidad |

8 |

46 disgusto |

2 |

8 calor |

38 |

21 secreción |

15 |

34 irritabilidad |

7 |

47 aroma |

2 |

9 molestia |

36 |

22 piel |

14 |

35 temperatura |

7 |

|

|

10 malestar |

35 |

23 fluido |

13 |

36 olor |

7 |

|

|

11 fuerza |

28 |

24 estímulo |

12 |

37 impureza |

5 |

|

|

12 vista |

25 |

25 sentimiento |

12 |

38 superficie |

4 |

|

|

13 sensación |

25 |

26 humedad |

11 |

39 nariz |

4 |

|

|

The analysis of our corpus reveals a significant tapestry of metaphors and fundamental analogies intricately interlaced into the discourse on women’s health. These linguistic constructions vividly portray conventional sociocultural perspectives on menstruation and how women face them, as emphasised by Northrup (2020). The significance of this revelation lies in recognising language as a medium that conveys deeply rooted beliefs.

To exemplify the correspondences related to the fundamental constructs in focus, some of the search findings are exhibited below in Table 2. In this context, the presented capture in Figure 1 depicts a search query for pathology- or illness-centred key nouns, displaying a primary mental conception defining the corpus. The substantial total frequency of these terms related to illness is notable, amounting to 119 occurrences (exclusively as nouns; key adjectives are additional). A sample of accompanying contextual segments is also provided to offer further insights into metaphorical assumptions and their lexical impact. It is worth noting that considering menstruation a pathology or insisting on its symptomatology conveys a figurative interpretation given the scientific evidence and the official recommendations for this cyclic phenomenon to be conceived as a natural process rather than as a disease. Continuous references to menstruation effects, signs, symptoms, pains, and incapacities may be cognitively identified by women as a confirmation that they are ill while menstruating, which is neither exact nor technically true.

Table 2. Frequency of illness-based key nouns with a sample of contextual segments.

Source: Sketch Engine

NOUN (5 items) /119 Total frequency (F) |

Noun |

Frequency |

1 enfermedad |

59 |

2 malestar |

31 |

3 patología |

21 |

4 sufrimiento |

7 |

5 dolencia |

1 |

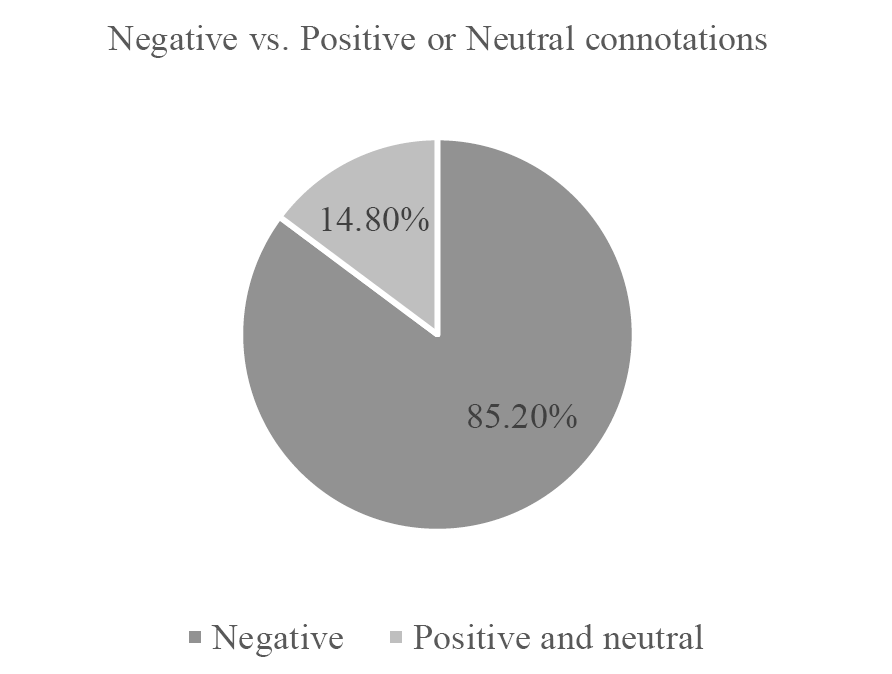

Figure 1. Sample of contexts for ’patología’. Source: Sketch Engine

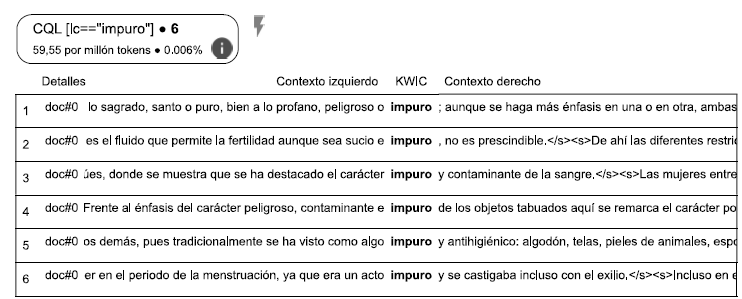

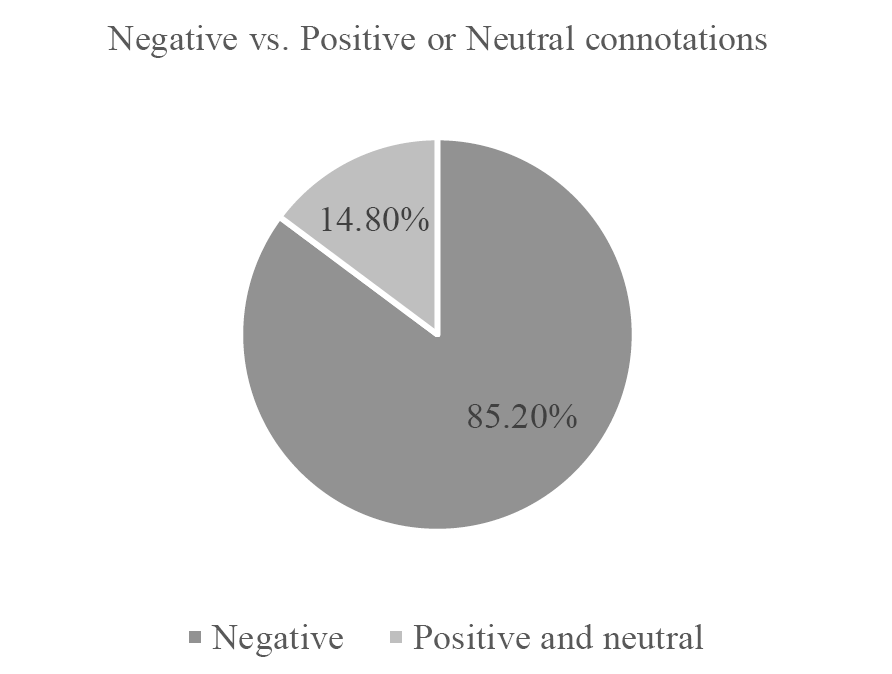

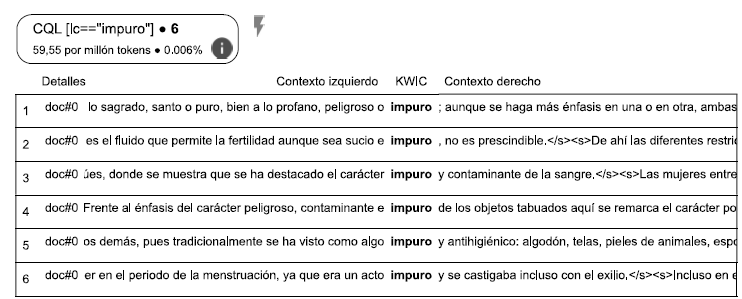

The sample below corresponds to a short collection of recurring nouns with meanings close to the concept of hygiene, dirt, impurity, and their frame semantic field. The contextual examples exposed contain hygiene-based key adjectives, but the content they refer to is determining to understand a wide range of figurative patterns concerning menstruation which are frequently remarked on all over the ages, persisting to the present.

It is interesting to refine that the contextual display of these key adjectives encompasses not only their literal meaning but also a figurative sense, which is visibly influenced by cultural, religious, or mythological factors among others. What we can find frequently expressed in the corpus is not only a set of allusions to dirt or unhygienic circumstances but also some references to spiritual impurity or contamination. This final inference is very revealing to understand the extent to which menstruation may have been prejudiced and gendered, which is likely to have affected and probably still affects women’s cognitive interpretation of their condition when menstruating.

Table 3. Frequency of hygiene-based key nouns with a sample of contextual segments including hygiene-based key adjectives. Source: Sketch Engine

NOUN (5 items) /37 Total frequency (F) |

Noun |

Frequency |

1 higiene |

22 |

2 impureza |

5 |

3 olor |

4 |

4 suciedad |

3 |

5 asco |

3 |

Figure 2. Sample of contexts for ’impuro’ and ’sucio’ as adjectives. Source: Sketch Engine

In the following figure, the affluence of key nouns related to shame, embarrassment, and taboo is evident, providing a direct explanation for the presence of terms related to concealment, silence, distance, and references to limitation or handicaps, among other similar notions. The contextual selection, with ’embarrassment’ as a core term, contains a substantial visual representation of prevalent metaphors resulting in stereotypes on menstruation, which may have prompted women to camouflage their condition on numerous occasions.

It is convenient to bear in mind that the frequency of these perception keywords is relevant in the corpus not only due to the number of occurrences but also given the scientific character of the publication which originated the compilation (Colomer Ed., 2023). In fact, it could be verified in our analysis that the abundance of some perception nouns and adjectives is evident, despite the preliminary assumption of objectivity we may associate with science and medicine (Hyland, 2010). Additionally, the biased sense of such key terms and the contexts they are integrated into also unveils evidence of gendered discourse.

Table 4. Frequency of taboo- and concealment-based key nouns with a sample of contextual segments including embarrassment as a core term. Source: Sketch Engine

NOUN (9 items) /83 Total frequency (F) |

Noun |

Frequency |

1 tabú |

22 |

2 vergüenza |

19 |

3 aislamiento |

10 |

4 distancia |

8 |

5 silencio |

8 |

6 ocultamiento |

7 |

7 mito |

4 |

8 reclusión |

3 |

9 limitación |

2 |

Figure 3. Sample of contexts for ’vergüenza’. Source: Sketch Engine

4.2. Stereotyped beliefs and gendered attitudes

The most prevalent metaphorical patterns related to menstruation are presented in the following table, offering an overview of the most common ones to provide a comprehensive understanding of the cognitive constructs that may influence women and their health. Notably, health and hygiene are frequently referenced, often intertwined with taboos or shame, as well as terms associated with silence or concealment. The recurring notion of limitation is also substantial, reflecting the impact of the unfavourable atmosphere created by these metaphorical representations.

Table 5 discloses a general overview of the main metaphorical segments and their basic interpretation in the corpus. Interestingly, only one of the conceptions shows menstruation as a positive condition – that is when it refers to the origin of fecundation as the origin of a new life. The rest of the constructs are negative, adverse and in many cases visibly prejudiced.

Table 5. Recurring figurative patterns and common conceptions.

Source: Designed by the author from Sketch Engine results

Health |

Hygiene |

Need for camouflage and origin of limitations |

Menstruation= illness, pathology |

Menstruation= unhygienic period (with insistence on hygiene references) |

Menstruation= embarrassment, shame, humiliation, indignity… |

Menstruation= lack of harmony, imbalance, disorder |

Menstruation= impurity, dirt, and stains |

Menstruation= taboo, false beliefs, silence, and inaccurate health myth |

Menstruation= social disease |

Menstruation= disgusting smells, repugnant vapours, revulsion, repulsion |

Menstruation= seclusion, isolation, secret, need for distance… |

Menstruation= disease transmission vehicle |

Menstruation= poisonous agents, contaminant |

Menstruation= dark, muted, opaque and dull condition |

Menstruation= mood distortion, pain, tension, fear, lack of motivation, discouragement, and uncontrolled changes |

Menstruation= malignant fluids |

Menstruation= impediment, handicap, inability, limitation, and interference |

Menstruation= origin of life and fecundation– the only positive reference. |

Menstruation= decomposition |

Menstruation= annoying time, difficulties, dissuasive moment |

Menstruation results in à weakness, incapacity, negative mental condition, physical incompetence, unfitness, psychological debility, physical fragility, frailty. |

Menstruation results in à repugnance, rejection, disgust, discontent, resistance, antipathy… |

Menstruation results in à taboo, silence, distance, seclusion, isolation, reclusion, concealment, silence, social rejection, guilt, fears, contempt… |

A more in-depth contextual analysis uncovers a troubling reality conveyed by the discourse – the persistence of gender stereotypes and normalised imagery. Metaphors and emotionally charged language portray menstruation as a period associated with notions of illness, pain, apathy, dirt, impurity, repugnance, disgust, and the necessity for seclusion, concealment (Figure 4 below), or isolation in women, among other concepts. These exclusive associations, defining and impacting only women, have been scientifically normalised (Espejo-Martínez et al., 2019; Fernández Díaz, 2013), extensively propagated, and socially embraced for centuries, as evident in the observed contextual samples from the corpus (Table 5).

Figure 4. Example of recurring contexts with ’ocultamiento’ as a key noun. Source: Sketch Engine

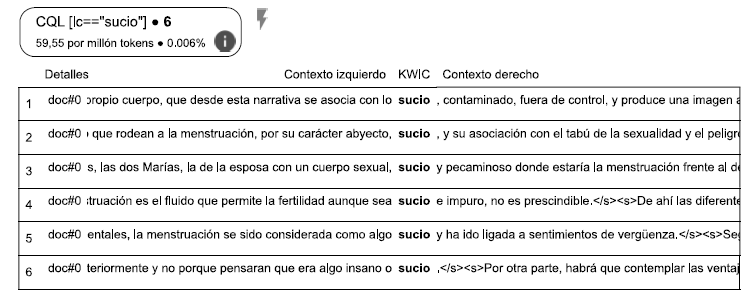

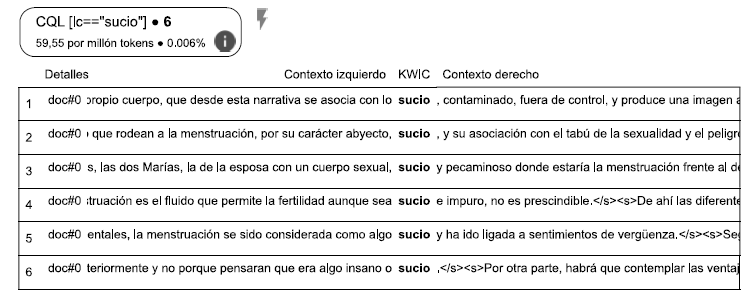

In terms of occurrences, most metaphorical associations are related to health, since menstruation is directly related to this women’s dimension. For example, the frequency of pathology-based perception terms is 119, whereas 37 occurrences in total correspond to key hygiene words (not all, but the basic ones) and 83 are references to taboos, embarrassment, concealment, or limitations arising from social rejection.

The following graph (Figure 5) shows the exact percentages of key nouns for each cognitive conception, which is of visual help to understand the effect of each one.

Figure 5. Occurrence of key nouns introducing metaphorical patterns.

Source: Designed by the author from Sketch Engine results

Significantly, with about 35% of terms referring to embarrassment, limitation and need for seclusion, the constructs we can consider the most prejudiced figurative conceptions are not only affluent but also revealing on the sociocultural effect the language of menstruation has and may have had.

Moreover, at first sight, it can be confirmed with the analysis of main contexts that the intensity of connotations related to the taboo-concealment group of nouns, is more notable than in the rest of the cases, although some hygiene contexts are also charged with an intense connotation of rejection.

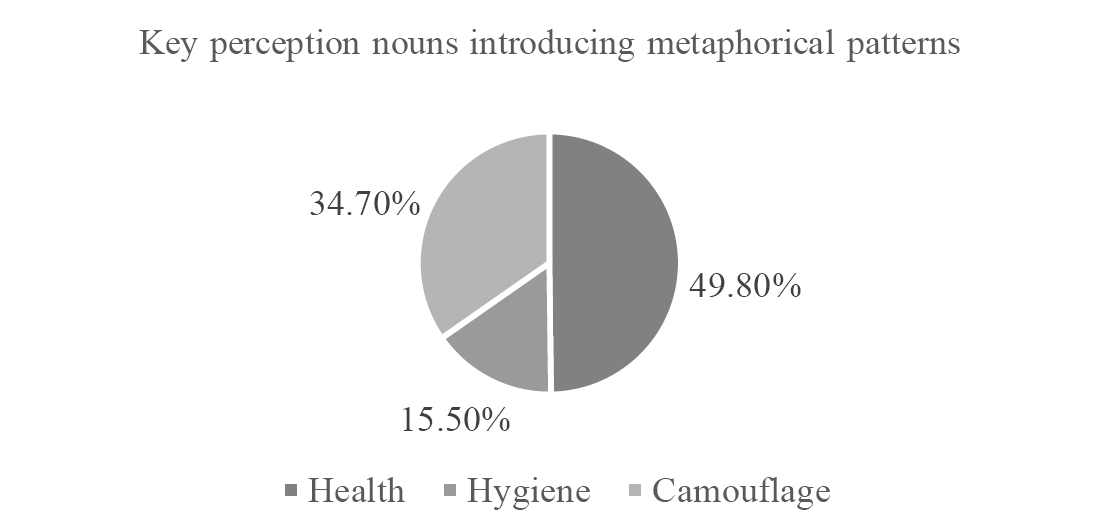

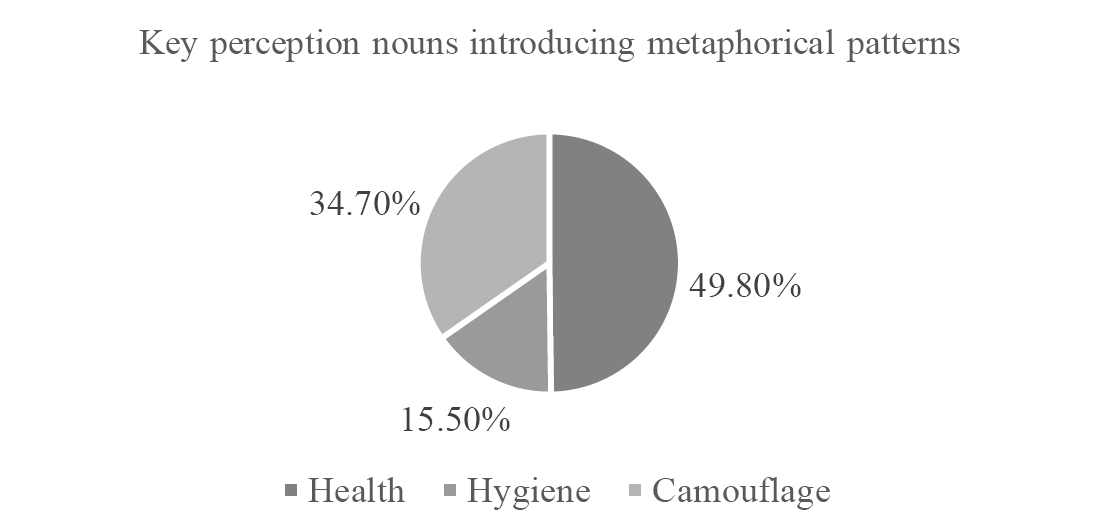

4.3. Impact of negative connotations

In the prevailing recurring elements and their respective contexts, the associations and emotions tied to menstruation predominantly gravitate towards the negative end of the spectrum. This prevalent negativity contributes to the reinforcement of gendered perceptions and biases surrounding women’s health. It is noteworthy, however, that one notable exception exists – instances where joy and positivity are commonly linked to menstruation, especially in the context of fecundation and fertility. Yet, across most cases, the discourse appears distinctly polarised, with negative effects or considerations not merely emphasised but almost exclusively referenced. In Figure 6, we can see how the connotations are distributed in figurative patterns. It shows how a significant majority of connotations related to menstruation through metaphorical content are adverse.

Figure 6. Connotations in metaphoric segments.

Source: Designed by the author from Sketch Engine results

The overwhelming prevalence of negative connotations uncovered in the corpus analysis prompts a critical reflection, particularly in light of the recommendations outlined by the World Health Organization (WHO) in their 2022 statement on Women’s Health Rights. The WHO emphasises the importance of recognising menstruation as a woman’s health condition, urging a shift from viewing it through the perspective of pathology, hygiene or stigma. In contrast, the notable number of negative conceptions identified in the discourse contradicts the WHO’s call for acknowledging the positive aspects of menstruation. This dissonance highlights a significant gap between the recommended approach and the prevailing language constructs in women’s health discourse.

Admitting the positive character of menstruation is fundamental not only to respecting women’s condition and promoting equality but also to preventing gender-based discrimination. The extensive presence of negative conceptions, as revealed by our analysis, calls for concerted efforts to foster more positive attitudes and cultivate inclusive language practices. Efforts in this direction are crucial to aligning with global initiatives that seek to destigmatise menstruation and promote a more respectful and equitable narrative.

Addressing this disjunction between recommended principles and the actual language use necessitates a multifaceted approach. Initiatives focusing on terminology, awareness (Cabré, 1999), and advocacy can play a crucial role in transforming social perceptions. Gender-sensitive resources aimed at healthcare professionals, scholars, educators, and the general public can contribute to dismantling ingrained stereotypes and fostering a more nuanced understanding of menstruation.

Moreover, media campaigns and public discourse initiatives can be instrumental in reshaping cultural attitudes. By promoting positive narratives and debunking myths surrounding menstruation, these efforts can contribute to creating an environment where women’s health is discussed openly, respectfully, and free from the burden of gender biases (Hennegan et al., 2021).

In conclusion, the dissonance between the prevalent negative connotations in women’s health discourse and the recommended positive approach by global health authorities calls for urgent attention and action. By embracing inclusive language, challenging stereotypes, and fostering positive attitudes, we can contribute to a cultural shift that respects and celebrates the natural and essential aspects of women’s health. This transformation is not only essential for individual well-being but also sustains the broader goals of gender equality and the promotion of women’s health rights on a global scale.

4.4. Gender-sensitive approaches and their expected influence on women’s experiences

The comprehensive exploration of metaphorical patterns within the discourse on menstruation has offered profound insights into the influential role these linguistic elements play in shaping social perceptions and cultural biases. Our examination has effectively demonstrated that recurring metaphors, coupled with prevailing connotations, are fundamental components that significantly influence the societal understanding of menstruation.

As proven in the corpus, menstruation is subjected to pathologisation, with symptoms magnified to depict it as a disease rather than a natural process. Moreover, references to dirt and lack of hygiene have been recurrent, extending to include mentions of disgusting smells and colours, contrary to the World Health Organization’s recommendations. This analysis reaffirms that menstruation is frequently portrayed as a phenomenon to be concealed, rooted in feelings of embarrassment, shame, and negative influence.

What emerges starkly from this analysis is the prevalence of negative connotations and emotions linked to menstruation. This exposes the pervasive presence of stigmatised beliefs and enduring stereotypes, significantly impacting how women’s experiences are perceived and communicated in the public sphere (Coupland, 2003). The language and discourse surrounding menstruation have long been entrenched with biases, contributing to a narrative that can adversely affect individuals experiencing menstruation (Weedon, 1987).

The results exhibit the enduring influence of conventional perceptions and biases preserved in women’s health discourse (Northup, 2020). These stereotypical conceptions have been expanded and culturally transmitted through language and specialised discourse, shaping women’s experiences and affecting their self-perception (Northup, 2020; Slade et. al., 2009). It becomes evident that specialised terminology plays an essential role (Alcaraz et al., 2007; Ciapuscio and Kuguel, 2002) in defining how women understand and relate to their own bodies and natural processes (Foucault, 1973).

Our findings emphasise the dire need for a gender-sensitive approach in women’s health discourse. Language is not just a tool for communication but a reflection of social values and beliefs. To foster a more inclusive and equitable society, it is imperative to address the deeply rooted stigmas and biases that language perpetuates.

Conclusively, the results of this study highlight the extensive influence of language on women’s health and experience. By unravelling the connotations and metaphors within menstruation discourse, we take a critical step towards challenging and reshaping cultural perceptions, ultimately fostering a more informed and gender-sensitive society. This journey from analysis to advocacy underscores the imperative for more respectful, inclusive, and gender-sensitive language practices as we strive to cultivate a linguistic landscape that respects, includes, and empowers women in discussions about their health and experiences.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The in-depth exploration of metaphors within the medical discourse on menstruation has yielded essential insights into their profound impact on cultural biases and social perceptions. This investigation effectively illustrates that recurring metaphors and persistent connotations in specialised and scientific publications are determining elements in shaping general attitudes and assumptions towards menstruation. Specifically, our analysis affirms the prevalent pathologisation of menstruation, figuratively magnifying or scorning its symptoms as if it were an annoying disease rather than a natural process. Additionally, references to dirt and hygiene-related negativity, including allusions to unpleasant smells and fluids, persist against WHO’s recommendations. Eventually, we have concluded that menstruation is shown as a phenomenon to be concealed, obscured, silenced, or masked due to the embarrassment, shame, and negative influence it allegedly entails.

Undoubtedly, a noteworthy revelation from our study is the prevalence of negative connotations and emotions linked with menstruation, uncovering deeply ingrained stigmatised beliefs and enduring stereotypes. These pervasive unfavourable perceptions significantly impact how women’s experiences are perceived and communicated within the public domain. On this point, our corpus analysis has proven that the metaphorical language surrounding menstruation has been entrenched with unsympathetic biases, perpetuating a narrative that can adversely affect individuals undergoing menstruation.

In response to these findings, our research assumes a broader mission – one committed to transforming gendered perceptions into more constructive and equitable alternatives. We firmly assert that employing gender-sensitive terminology is fundamental in challenging the existing circumstances. Through advocating for the creation and dissemination of inclusive language resources taking this research as a starting point, our project endeavours to disrupt the cycle of stereotypes and biases pervasive in women’s health discourse.

In essence, this research is intended to serve as a catalyst, emphasising the claim for more respectful, inclusive, and gender-sensitive language practices. As we move forward, our goal is to cultivate a society where women’s health language is not only precise and rigorous but also unprejudiced and respectful, laying the foundation for a more equitable and enlightened discourse.

REFERENCES

Alcaraz Varó, Enrique, José Mateo Martínez y Francisco Yus Ramos (Eds.), (2007). Las lenguas profesionales y académicas. Ariel

Baker, Mark C. (2003). Lexical Categories. Cambridge University Press.

Barona, Josep L. (2023). Naturaleza femenina y menstruación: genealogía de una construcción histórico-cultural. In La menstruación: de la biología al símbolo (pp. 19-77). Universidad de Valencia.

Berber Sardinha, Toni (2002). Corpora eletrônicos na pesquisa em tradução. Cadernos de Tradução, 1(9), 15-59.

Black, Max (1962). Models and Metaphors, Cornell University Press.

Blázquez Rodríguez, M. Isabel (2023). Análisis antropológico de la menstruación: del tabú al estigma, expresiones culturales y activismo. In La menstruación: de la biología al símbolo (pp. 133-198). Universidad de Valencia.

Bobel, Chris (2010). New blood: Third-wave feminism and the politics of menstruation. Rutgers University Press.

Bonilla Campos, Amparo (2023). La menstruación desde una aproximación psicológica. In La menstruación: de la biología al símbolo (pp. 79-132). Universidad de Valencia.

Botello Hermosa, Alicia and Rosa Casado Mejía (2017). Significado cultural de la menstruación en mujeres españolas. Ciencia y enfermería, 23(3), 89-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95532017000300089

Bowker, Lynne and Jennifer Pearson (2002). Working with specialized language. A practical guide to using corpora. Routledge.

Brown, Theodore. L. (2003). Making truth: Metaphor in science. University of Illinois Press.

Burrows, Anne and Johnson, Sally (2005). Girls’ experiences of menarche and menstruation. Journal of Reproductive and infant Psychology, 23(3), 235-249. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830500165846

Cabré, Mª Teresa (1999). La terminología: representación y comunicación. Elementos para una teoría de base comunicativa y otros artículos. Institut Universitari de Lingüística Aplicada.

Ciapuscio, Guiomar E. and Inés Kuguel (2002). Hacia una tipología del discurso especializado: aspectos teóricos y aplicados. In J. García Palacios (Ed.), Texto, terminología y traducción, (pp. 37-74). Almar.

Cifuentes Honrubia, José L. (1994). Gramática cognitiva. Fundamentos críticos. Eudema

Cimino, James J., Paul D., Clayton, George Hripcsak and Stephen B. Johnson (1994). Knowledge-based approaches to the maintenance of a large controlled medical terminology. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 1(1), 35-50.

Concise Medical Dictionary. (n.d.) Menstruation. In Oxfordreference.com. Oxford University Press. Retrieved December 12, 2023, from https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780199557141.001.0001/acref-9780199557141-e-6104.

Coupland, Nikolas (2003) Sociolinguistic Authenticities, Journal of Sociolinguistics, 7(3), 417-431. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9481.00233

Croft, William (1991). Syntactic Categories and Grammatical Relations: The Cognitive Organization of Information. University of Chicago Press.

Demjén, Zsófia., & Semino, Elena (2016). Introduction: Metaphor and language. In The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language (pp. 19-28). Routledge.

Dirckx, John. H. (1976). The language of medicine: its evolution, structure and dynamics. Harper and Row.

Donat Colomer, Francisco (Ed.). (2023). La menstruación: de la biología al símbolo. Universitat de València.

Donat Colomer, Francisco (2023). La menstruación desde el punto de vista biológico. In La menstruación: de la biología al símbolo (pp. 199-248). Universidad de Valencia.

Donat Colomer, Francisco (2023). Alteraciones de la menstruación. En La menstruación: de la biología al símbolo. (pp. 249-308). Universidad de Valencia.

Espejo Martínez, Ana B., Mª Teresa González Lucena, Belén Garrido Luque and Mª Ángeles Álvarez Soriano (2019). Ginecología y obstetricia ¿Influye el género? In M.T. Ruiz Cantero (Coord.) Perspectivas de Género en Medicina, Monografías 39 (pp. 206-236). Fundación Dr. Antoni Esteve.

Fernández Díaz, Edulgerio (2013). La cuestión del género, ¿Un aporte a la comprensión de la mujer? Una reflexión desde la bioética personalista. Revista del Cuerpo Médico Hospital Nacional Almanzor Aguinaga Asenjo, 6(4), 47-56.

Foucault, Michael (1973). The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. Routledge.

Gentner, Dedre and Donald R. Gentner (1983). Flowing waters or teeming crowds: Mental models of electricity. Mental models, 99, 129. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781315802725-10

Gómez-Sánchez, Pío I., Yaira Y. Pardo-Mora, Helena P. Hernández-Aguirre, Sandra P. Jiménez-Robayo and Juan C. Pardo-Lugo (2012). Menstruation in history. Investigación y Educación en enfermería, 30(3), 371-377.

Gordon, David and George Lakoff (1971). Conversational postulates. Papers from the Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, 7, 63-84.

Gottlieb, Alma (2020). Menstrual taboos: Moving beyond the curse. The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies, 143-162. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_14

Gotti, Maurizio and Françoise Salager-Meyer (Eds.), (2006). Advances in medical discourse analysis: Oral and written contexts (Vol. 45). Peter Lang.

Halliday, Michael A.K. (1978). Language as Social Semiotic. Arnold.

Halliday, Michael A.K. (1994). An Introduction to Functional Grammar. Arnold.

Hennegan, Julie, Inga T. Winkler, Chris Bobel, Danielle Keiser, Janie Hampton, Gerda Larsson, Venkatraman Chandra-Mouli, Marina Plesons and Thérèse Mahon (2021). Menstrual health: a definition for policy, practice, and research. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 29 (1), 31-38. https://doi.org/10.1080%2F26410397.2021.1911618

Hyland, Ken (2010). Constructing proximity: Relating to readers in popular and professional science. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 9(2), 116-127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2010.02.003

Idoiaga-Mondragon, Naia. and Belasko-Txertudi, Maitane (2019). Understanding menstruation: Influence of gender and ideological factors. A study of young people’s social representations. Feminism & Psychology, 29(3), 357-373.

Jackson, Theresa E., and Falmagne, Rachel J. (2013). Women wearing white: Discourses of menstruation and the experience of menarche. Feminism & Psychology, 23(3), 379-398. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0959353512473812

Jeoung, Hannah (2023). Pathological Periods: Analysis of the Limited Discourse and Stigmatization of Menstruation. Pathways: Stanford Journal of Public Health (SJPH), 1(1).

Johnston-Robledo, Ingrid and Chrisler, Joan C. (2020). The menstrual mark: Menstruation as social stigma. The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies, 181-199. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kuhn, Thomas S. (1979). Metaphor in science. Metaphor and thought, 2, 533-542. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139173865.024

Langacker Ronald W. (2008), Cognitive Grammar. A Basic Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Leech, Geoffrey, Brian Francis and Xunfeng Xu (1994). The use of computer corpora in the textual demonstrability of gradience in linguistic categories. In C. Fuchs and B. Victorri (Eds.), Continuity in linguistic semantics (pp. 57-76). John Benjamins.

Leech, Geoffrey (2007). New resources, or just better old ones? The holy grail of representativeness. In M. Hundt, N. Nesselhauf, and C. Biewer (Eds.), Corpus linguistics and the web (pp. 133-150). Rodopi.

Luke, Haida (1997). The gendered discourses of menstruation. Social Alternatives, 16(1), 28-30.

Margaix Fontestad, Lourdes (2023). Cuidados durante la menstruación. In La menstruación: de la biología al símbolo (pp. 309-355). Universidad de Valencia.

McHugh, Maureen C. (2020). Menstrual shame: Exploring the role of ’menstrual moaning’. The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies, 409-422. Palgrave Macmillan. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_32

Mungra, Philippa (2007). Metaphors among titles of medical publications: An observational study. Ibérica, Revista de la Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos, (14), 99-121.

Navarro-Fernando, Ignasi (2016). Metaphorical aspects in cancer discourse. In P. Ordóñez-López and N. Edo-Marzá (Eds.), Medical Discourse in Professional, Academic and Popular Settings, (pp.125-148), Multilingual Matters.

Navarro-Ferrando, Ignasi (2017). Conceptual metaphor types in oncology. Ibérica, 34, 163-186.

Newton, Victoria L. (2016). Everyday discourses of menstruation. London: Palgrave Macmillan. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-48775-9

Northup, Christiane (2020). Women’s Bodies, Women’s Wisdom: Creating Physical and Emotional Health and Healing (Revised 5th Edition). Bantam.

Pao, Vaveine P. S. (2023). Social Stigma Centred around Menstruation: A Reflective Review. Frontier Anthropology, 11, 51-58.

Patterson, Ashley (2014). The social construction and resistance of menstruation as a public spectacle. Illuminating how identities, stereotypes and inequalities matter through gender studies, 91-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8718-5_8

Salager-Meyer, Françoise (1994). Hedges and textual communicative function in medical English written discourse. English for specific purposes, 13(2), 149-170. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0889-4906(94)90013-2

Semino, Elena (2008). Metaphor in discourse (p. 81). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Semino, Elena (2011). The adaptation of metaphors across genres. Review of Cognitive Linguistics. Published under the auspices of the Spanish Cognitive Linguistics Association, 9(1), 130-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1075/bct.56.07sem

Semino, Elena, John Heywood and Mick Short (2004). Methodological problems in the analysis of metaphors in a corpus of conversations about cancer. Journal of pragmatics, 36(7), 1271-1294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2003.10.013

Sketch Engine (2023), Sketch Engine [Software]. http://www.sketchengine.eu

Slade, Pauline, Annette Haywood and Helen King (2009). A qualitative investigation of women’s experiences of the self and others in relation to their menstrual cycle. British journal of health psychology, 14(1), 127-141. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910708x304441

Song, Michael M., Cheryl K., Simonsen, Joanna D. Wilson and Marjorie R. Jenkins (2016). Development of a PubMed Based Search Tool for Identifying Sex and Gender Specific Health Literature. Journal of Women’s Health, 25(2), 181-187. http://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2015.5217

Sontag, Susan (1978). Illness as Metaphor. Straus and Giroux.

Timofeeva-Timofeev, Larissa. and Chelo Vargas-Sierra (2015). On terminological figurativeness: From theory to practice. Terminology. International Journal of Theoretical and Applied Issues in Specialized Communication, 21(1), 102-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1075/term.21.1.05tim

Ussher, Jane M., and Perz, Janette (2014). «I Used to Think I Was Going A Little Crazy»: Women’s resistance to the pathologization of premenstrual change. In Women Voicing Resistance (pp. 84-101). Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203094365-6

Vargas-Sierra, Chelo (2012). La tecnología de corpus en el contexto profesional y académico de la traducción y la terminología: panorama actual, recursos y perspectivas. In M.A. Candel Mora and E. Ortega Arjonilla (Coords.), Tecnología, Traducción y Cultura, (pp. 67–99). Tirant Lo Blanch.

Weedon, Chris (1987). Feminist practice and poststructuralist theory. Blackwell.

Wilce, James M. (2009). Medical discourse. Annual review of anthropology, 38, 199-215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-091908-164450

Wood, Jill M. (2020). (In) visible bleeding: the menstrual concealment imperative. The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies, 319-336. Palgrave Macmillan. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_25

World Health Organisation (2022), Statement on Menstrual Health and Rights. 50th Session of the Human Rights Council. United Nations Agency for Global Health and Safety.

Yanoff, Karin L. (1988). The rhetoric of medical discourse: An analysis of the major genres. University of Pennsylvania.

Zeidler, Pawel (2013). Models and metaphors as research tools in science (Vol. 10). LIT Verlag Münster.

Notas

1 This publication forms part of the research project «Digitisation, processing and online publication of open, multilingual and gender-sensitive terminology resources in the digital society (DIGITENDER)» (TED2021-130040B-C21), funded by Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Agencia Estatal de Investigación (10.13039/501100011033) and by the European Union «Next GenerationEU»/Plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia. [Volver]