Cultura, lenguaje y representación / Culture, Language and Representation

Pérez-Hernández, Lorena (2024): Metaphorical Conceptualization of the Big M. Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación, Vol. XXXIV, 59-82

ISSN 1697-7750 · E-ISSN 2340-4981

DOI: https://doi.org/10.6035/clr.7743

Universitat Jaume I

Metaphorical Conceptualization of the Big M

Conceptualización metafórica de la menopausia

Artículo recibido el / Article received: 2023-10-30

Artículo aceptado el / Article accepted: 2024-04-25

Resumen: A lo largo de la historia, la menopausia ha sido considerada alternativamente como un pecado, un tipo de neurosis, una enfermedad o una deficiencia. Recientemente ha sido reinterpretada de forma más positiva como un nuevo comienzo, un viaje de autodescubrimiento o una especie de energía interior. Cada una de estas conceptualizaciones metafóricas refleja una ideología particular asociada a perspectivas religiosas, biomédicas y feministas, entre otras. Sin embargo, el discurso de las mujeres sobre la menopausia ha sido históricamente escaso, ocultado y silenciado por el tabú social que rodea este tema. Esto ha cambiado en las últimas décadas al comenzar las mujeres a hablar abiertamente sobre sus experiencias menopáusicas en los medios de comunicación. Adoptando como marco el Análisis Crítico de la Metáfora, este estudio investiga la conceptualización contemporánea de la menopausia de las mujeres británicas. Los estudios sobre las metáforas de la menopausia son escasos y a menudo se llevan a cabo desde una perspectiva biomédica o sociológica (feminista), los dos contextos en los que tradicionalmente ha tenido lugar la mayoría de las conversaciones sobre la menopausia. Analizamos una colección de 300 expresiones metafóricas procedentes de testimonios de mujeres sobre su experiencia, sentimientos y pensamientos sobre la menopausia. El análisis cualitativo de los datos ofrece un retrato detallado de los marcos metafóricos que subyacen al discurso de las mujeres contemporáneas sobre la menopausia. Esta investigación pretende dar voz en este tema a las protagonistas reales: las mujeres que están atravesando una fase relevante de sus vidas.

Palabras clave: menopausia, metáfora conceptual, Análisis Crítico de la Metáfora, lingüística cognitiva.

Abstract: Throughout history, menopause has alternatively been framed as either a sin, a type of neurosis, a disease, or a deficiency. Only recently, it has been re-framed under a more positive light as a new beginning, a journey of self-discovery, or a sort of internal zest. Each of these metaphorical conceptualizations of menopause reflects a particular ideology stemming from religious, biomedical, and feminist viewpoints, among others. Women’s talk about menopause, however, has been historically scarce, hidden and silenced by the social taboo surrounding this matter. This has changed in the past few decades, with women openly talking about their menopausal experiences in the media. Adopting a Critical Metaphor Analysis framework, this study investigates contemporary women’s conceptualization of menopause as reflected on the metaphors they use to talk about it. Studies on the metaphors of menopause are scarce and often carried out from a biomedical or sociological (feminist) perspective, the two contexts in which most talk about menopause has traditionally taken place. We analyze a collection of 300 metaphorical expressions stemming from a multi-source corpus of women’s testimonials about their experience, feelings, and thoughts about menopause. The qualitative analysis of the data offers a fine-grained portrayal of the metaphorical frames that underlie the discourse of contemporary women about menopause. Through our investigation, we aim to ultimately give the floor on this topic to the real protagonists: those ordinary women who are undergoing a relevant phase of their lives.

Key words: menopause, conceptual metaphor, Critical Metaphor Analysis, cognitive linguistics.

1. INTRODUCTION

Metaphors play a pivotal role in shaping our perceptions and understanding of complex topics. They map our knowledge from familiar domains onto abstract ones, thus serving as powerful tools for comprehension and communication, amounting to approximately 20% of our discourse (Steen et al., 2010). Over the past few decades, research has shown that metaphors can mold our thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and even our recollections (Sontag, 1978; Lakoff and Johnson, 1980; Lakoff, 1987; Thibodeau & Boroditsky, 2011; Thibodeau et al., 2019). In this study, we delve into the intricate world of the metaphorical conceptualization of menopause. Society has traditionally placed a taboo on this natural phase of women’s life, thus imposing silence on a topic that many women still do not feel at ease talking about. This silence mandate reflects itself in the names commonly used to refer to menopause (e.g., the big M, the change, the visitor, etc.), which often involve metonymies, metaphors, and other patterns of conceptual interaction to avoid literal reference. The discourse of menopause has often been circumscribed to medical settings, where it has been conceptualized as a condition that needs treatment due to its associated negative physical, emotional, and social consequences (see Niland, 2010 for a comprehensive summary of this view). The negative portrayal and subsequent medicalization of menopause in the biomedical discourse has been contested by several waves of feminist movements and cross-cultural sociological studies which have surfaced a more diverse, as well as positive conceptualization of menopause (see Dickson, 1990; and Quental et al. 2023 for an overview).

It has become increasingly apparent that there is a crucial need to shift our gaze from a medicalized discourse of menopause towards the actual narratives and testimonies of women experiencing it. These first-hand accounts represent an invaluable resource for uncovering alternative metaphorical frames that can reshape the discourse around menopause. However, in-depth analyses of the metaphorical conceptualization of menopause within cognitive linguistics and conceptual metaphor theory are scarce (Bogo Jorgensen, 2020, 2021, 2022). In our study, we embark on this vital journey, emphasizing the exploration of women's personal stories and experiences during menopause. By delving into their narratives, we specially aim to unearth the metaphorical frames they use to talk about this phase of life. This endeavor may not only acknowledge the diversity of women's experiences but also allow for a more balanced and empowering perspective on menopause, one that also celebrates its unique aspects and fosters a more supportive societal understanding of this natural phase of life.

We approach this objective from a Critical Metaphor Analysis theoretical framework (Charteris-Black, 2004; Wodak and Meyer, 2009; Hart, 2019), and we aim at contrasting biomedical and feminist metaphorical conceptualizations of menopause, both ideologically charged visions of the matter under consideration, with those emerging from the analysis of the everyday life language used by real contemporary women. The final aim is to offer a faithful and updated view of what menopause means for those who experience it firsthand.

The study is based on a collection of 300 metaphorical expressions stemming from testimonials of menopausal, perimenopausal, and postmenopausal British women. For each metaphorical expression, their source and target domains have been identified and classified in relation to their axiological portrayal of menopause, and their discourse function (descriptive or evaluative). A detailed qualitative analysis of the most pervasive metaphors in the data has then been carried out to unveil the characteristics of contemporary women’s views of menopause as reflected in their metaphorical language.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical tools adopted for the present study and an overview of previous studies on the metaphorical conceptualization of menopause. Section 3 includes methodological considerations regarding the criteria for corpus selection, the protocol for metaphor identification, and the data annotation scheme. Section 4 offers a description and discussion of the four main conceptual metaphors of menopause identified in the analysis. The final section summarizes the main findings of the study and suggests some paths for further research.

2. CRITICAL METAPHOR ANALYSIS AND THE METAPHORICAL CONCEPTUALIZATION OF MENOPAUSE

The appeal of metaphors hinges on the user’s familiarity with the source domain, which offers knowledge and convenient expressions to understand and talk about a more abstract notion. In addition, their persuasive power has also been attested in the literature (Charteris-Black, 2011; Musolff, 2017). However, as Rosenblueth et al. (1943) rightly warned us, «the price of metaphor is eternal vigilance.» While metaphorical conceptualization is often convenient, it also conceals potential risks because concepts and reasoning patterns established in one domain (the source) are employed in another domain (the target) with the implicit assumption that they transfer with reasonably accurate validity. Even when used merely as a shortcut, and maybe in a colloquial manner, we tend to adopt the thought patterns of the more familiar source domain to reason and talk about the target domain. These framing effects of conceptual metaphor and their influence on how we perceive, act upon, and even recall facts have been unveiled in the works by philosophers, linguists, and psychologists (Sontag, 1978; Lakoff and Johnson, 1980; Thibodeau & Boroditsky, 2011; Pérez-Hernández and Pérez Sobrino, 2024). The choice of a metaphor against others is not inconsequential. Metaphors may lead to different emotional reactions and diverse logical conclusions about a topic (Hart, 2019). They can also divert attention to some aspects of a matter, while blinding us about other equally relevant issues. In this connection, metaphor is a powerful ideological tool as has been extensively argued in a large body of literature carried out within Critical Metaphor Analysis, which also involves the exposure of biased metaphors, the promotion of an active resistance against them, and the creation of alternative, more appropriate mappings to reframe discourse on certain topics (Charteris-Black, 2004; Wodak and Meyer, 2009; Hart, 2019). Among them, there are investigations on the replacement of metaphors about immigration (Santa Ana, 2002), the misleading assumptions of science metaphors (Nerlich and Hellsten, 2004), the ineffectiveness and potential risk of cancer metaphors (Sontag, 1978; Hauser and Schwarz, 2015; Hendricks et al., 2018; Semino et al., 2016), the more recent re-frame Covid initiative (Olza et al., 2021; Pérez Sobrino et al., 2022), and works on metaphor on climate change (Flusberg et al.,2017).

The notion of metaphor resistance has been amply dealt with in Gibbs and Siman (2021), who pointed out the need speakers have of sometimes resisting or rejecting metaphors for various reasons: their meaningfulness, their incoherence, their lack of explanatory power, their creation of interpretation biases (e.g. in science), the inferences they may trigger about a particular issue in different contexts (e.g., the war metaphor in relation to cancer or COVID), their stigmatization of a social group, etc. Additionally, as shown in Wackers et al. (2021), since metaphors are a matter of thought, language, and communication, they can be resisted in one or more of these dimensions. Yet another factor affecting the resistance against a metaphor has been shown to be their offensive or derogatory nature, with «extreme metaphors» of this type being more readily «resisted» by speakers (de Lavalette et al., 2019; Hart, 2021).

To be effective, resistance metaphors should be linked to existing ones through the preservation of the same source domain (Santa Ana, 2002; Wackers and Plug, 2022). By way of illustration, Santa Ana (2002: 298) suggests that if, for instance, immigrants are metaphorically conceptualized as flowing water, it would be a good idea to preserve the same source domain while enriching it with new positive values as in «in the American Southwest, the immigrant stream makes the desert bloom.»

Still, the emergence of new metaphors that oppose existing ones to subvert their negative assumptions is a heterogeneous process. As observed in Gibbs and Siman (2021), there are many ways in which new metaphors can stand up against previous metaphorical conceptualizations. Speakers may dislike and resist a particular metaphor (e.g., I prefer to think of my cancer treatment as a journey rather than a war). But this rejection may also be partial and affect only certain aspects of a metaphorical mapping (e.g., in the love is a Journey metaphor, people may like the fact that love surmounts all obstacles but dislike the fact that love journeys are often plagued with interruptions and changes of itinerary). It is also possible to find contradictory positions in people’s resistance of metaphors (e.g., important is big, but «Good things come in small packages»). Conscious rebellion about a metaphor in a particular setting does not necessarily reflect a total rejection of that metaphor in all contexts. Metaphors can be resisted individually, as the result of personal experience (i.e., war metaphor against cancer, Sontag (1978)), or collectively, such as the immigration is flowing water metaphor, identified in Santa Ana et al. (1998) and since then amply condemned in subsequent studies (Santa Ana, 2002; Hart, 2010; Montagut & Moragas-Fernández, 2020; Porto, 2022). There are other cases in which the opposition to metaphors comes naturally from the speakers themselves rather than being the result of scientific analysis, and experts’ proposals. In this connection, Hart (2011) showed how readers rejected the inferences derived from radical anti-immigration metaphors.

The remainder of this section offers a summary of those metaphors of menopause that have conformed the main discourses about this matter to date. This will allow a comparison with those metaphors in use in UK women’s present-day talk about this topic and shed light on their adherence or resistance to those traditional mainstream metaphors of menopause. As Lazar et al. (2019) point out, menopause is a major life change often expressed in semantically dense figurative language. Its conceptualization often falls into one of two fragmentary and reductionist views which focus either on its biological or sociocultural dimensions (Voda and George, 1986).

The biomedical portrait of menopause makes use of the breakdown metaphor, based on the more general women’s bodies as reproductive machines. It conceptualizes this event as a factory (ovarian factory) that is failing, resulting in failed production (deficiency of reproductive hormones) and, therefore, leading to degeneration, loss of femineity and ageing (Martin,1987). This view goes back to the middle 20th century when menopause was also considered a struggle against the consequences of such breakdown (Deutsch, 1945). Metaphors at work in the biomedical conceptualization of menopause largely overlook its positive side (see Niland, 2010 for an exhaustive account).

The sociocultural view of menopause emerged in 1970s in reaction to the biomedical view and its medicalization (Dickson, 1990). Menopause is conceptualized as a natural process or phase of life, as well as a culturally constructed heterogeneous event that is diversely conceptualized as either a conflict or critical point in western culture, or a period with a high social prestige in eastern societies (Flint, 1975; Wilbush, 1982). As observed by Charlap (2015), some cultures even lack a word to describe this life process. Kabir and Chan’s (2023) meta-analysis of twelve papers focusing on menopausal experiences of Chinese women showed that cultural stereotypes could even have an impact on how they perceived their menopausal symptoms. In the same line, Jin et al. (2015) argue that Asian midlife women, notably Chinese, have lower rates of physical and psychological symptoms and more favorable attitudes regarding menopause than other ethnic groups. The sociocultural understanding of menopause has also changed over time. Thus, it has been variously conceptualized as a sin in Victorian times, as neurosis in the early 20th century, as a disease in the late 20th century, and either as a health condition/issue or a natural phase of life in recent times.

Menopause metaphors found within the sociocultural, feminist stance are resistance metaphors that focus mainly on its positive aspects. Zeserson (2001) identified the metaphor ‘chi no michi’ (path of blood) in the discourse about menopause of Japanese women, where blood metonymically stands for women, and showed how this metaphor challenges purely biomedical explanations and amounts to resistance against globalizing definitions of the embodied experience of menopause. In this connection, in a study aimed at improving human-computer interaction systems, Lazar et al. (2019), analyzed women’s talk about menopause in a Reddit forum and found that they made use of certain recurring conceptual projections. Thus, menopause was conceptualized as either a stranger in the body (an alien, a beast, or a possessor), a journey, an expiration date, or a learning process. From a feminist literary criticism approach, Quental et al. (2023) unveiled certain metaphors aimed at destigmatizing menopause in the works of contemporary feminist writers (Margaret Mead, Virginia Woolf, and Julia Kristeva), as well as in a collection of women’s testimonials in 150 articles published in The Guardian between 2005 and 2020. These metaphors included: (1) «killing the angel in the house» (liberation from gendered social expectations and from the reproductive mandate), (2) discovering the «foreigner» within; and (3) the [menopause] «zest».

All in all, since the 19th century to our days, the discourse about menopause has gone from an initial silencing to a rise in awareness based on its negative physical, psychological, and emotional aspects, its subsequent stigmatization, and a recent re-framing in a more positive view. As Geddes (2022) points out, menopause «is having a moment» with a rise of news coverage in the media (Orgard and Rottenberg, 2023). Despite this rise in visibility, specific studies about the metaphorical conceptualization of menopause are scarce. This paper attempts to fill this gap by analyzing the metaphors about menopause in the discourse of a collection of present-day perimenopausal, menopausal, and postmenopausal UK women.

3. CORPUS AND METHODOLOGY

This section describes the criteria for corpus selection, the protocol for metaphor identification, and the data annotation scheme. Albeit being qualitative in nature, the present study adopts a corpus-based approach with data stemming from actual communicative use. The sampling for analysis consists of 300 metaphorical expressions about menopausal experiences retrieved from a variety of sources. Compared to simple Google searches, the sources chosen for analysis were selected to ensure the diversity and representativity of the sample.

To guarantee the diversity of the corpus, sources include testimonials of women talking about their menopausal experience in different contexts, from private online clinics websites to non-profit online health charities, the media, academic archives, or associations of women activists:

- menopause websites and online clinics aimed at commercializing a variety of advisory and medical services related to menopause:

The Menopause Centre [www.mymenopausecentre.com]

Health and Her [www.healthandher.com]

Medical Prime [www.medicalprime.co.uk]

- commercial companies:

Boots-Menopause Stories [www.boots.com]

- non-profit health charities aimed at educating and advising women and the general public about menopause and related issues (e.g. nutrition during menopause):

The Menopause Charity [www.themenopausecharity.org]

British Nutrition Foundation

[https://www.nutrition.org.uk]

- associations of women activists:

Menopause Mandate [www.menopausemandate.com]

- the media, including newspapers, magazines, and TV broadcasts offering testimonials of well-known public figures, as well as of non-public local women:

The Guardian [www.theguardian.com]

The Courier [www.thecourier.co.uk]

The Daily Mail [www.dailymail.co.uk]

BBC [https://www.bbc.com]

- academic websites:

The Silent Archive-University of Leicester-Spoken testimonies of menopause [https://le.ac.uk/emoha/themes/the-silent-archive]

University of Leeds

[https://ahc.leeds.ac.uk/]

Emma’s menopause blog (University of Huddersfield)

[https://www.hud.ac.uk/news/wellbeing-blogs/emmas-menopause-blog/]

University of Warwick

[https://warwick.ac.uk/services/socialinclusion/projects/groups/personalstories/#menopause]

To minimized potential biases in the selection of the examples and to maximize the representativity of the final corpus, I gathered the first metaphorical expressions from each of the websites, in order of appearance, until the number of required examples was obtained (50 examples per source type). Table 1 illustrates the distribution of the metaphorical expressions comprising the final corpus per source type.

Table 1. Metaphorical expressions per source type

|

N |

Clinics |

50 |

Menopause Center 29 |

Health and Her 13 |

Medical Prime 8 |

Commercial Companies |

50 |

Boots 50 |

Non-profit Health Charities |

50 |

The Menopause Charity 43 |

British Nutrition Foundation 7 |

Associations of Women Activists |

50 |

The Menopause Mandate 50 |

Media |

50 |

The Guardian 14 |

The Daily Mail 12 |

The Courier 13 |

BBC 11 |

Academics |

50 |

U. Leeds 3 |

U. Warwick 25 |

U. Huddersfield 9 |

Silent Archives 13 |

TOTAL |

300 |

Sources include testimonials from women talking about their diverse menopausal experiences with symptoms raging from mild to severe, thus further contributing to the variety and representativity of the final corpus of data.

The texts were carefully examined to identify metaphorical expressions that women used to describe their experiences with menopause. Since the automatic identification of metaphors is not yet possible, the retrieval of metaphorical expressions was carried out in accordance with the protocol outlined in the Metaphor Identification Procedure of the Vrije Universiteit-MIPVU (Steen et al., 2010: 769). This method includes several systematic steps for identifying metaphor-related utterances. As per the MIPVU procedure, the meanings of words in the selected expressions were cross-checked in a dictionary to determine if a more basic, concrete, human-related meaning could also fit the context of the utterance. If such a basic meaning could be identified for a word and if the contextual and basic meanings were distinct but related by some similarity (e.g., navigate and sail menopause), then the expression was marked as potentially involving a metaphor. This protocol has been adapted to the needs and characteristics of the present study as follows.

- Identification of target domains. Since all testimonials have as their main goal to explain the menopausal experience of the speaker (i.e. its physical and emotional symptoms, social consequences, duration, etc.), it was hypothesized that the general target domain is the notion of menopause itself or of some of its symptoms. These different dimensions of the notion of menopause, as the target domains, are the recipients of the positive and negative inferences generated by the metaphors at work.

- Identification of source domains. Once a specific dimension of the target domain has been identified in step 1, I proceeded to analyze the rest of the co-text in search of verbal elements conveying descriptive or evaluative information about it. Among them, those that comply with the requirements of the MIPVU procedure, as described above, were annotated as potential source domains.

- Identification of conceptual mapping. In this step of the process, it was determined whether the mapping connected two independent concepts or whether it took place within one single domain. Only in the first case was the mapping considered an instance of metaphor. Additionally, the transition from linguistic to conceptual metaphor was based on careful consideration of the full co-text containing the linguistic examples. Thus, a linguistic metaphor was only coded as a potential conceptual metaphor if additional terms in the co-text or in other testimonials corroborated the choice of source domain. Additionally, previous studies on metaphors and existing classifications of conceptual metaphor repositories (i.e., the MetaNet Metaphor Wiki; Dodge et al. 2015; Grady’s (1997) classification of primary metaphors) were also consulted in the process of metaphor identification. Most disagreements were due to coding errors that were resolved through discussion.

- Control of analysts’ bias. The coding process was performed by a linguistics graduate student, a cognitive linguistics doctoral student, and the author herself. The graduate student received specific instruction on conceptual metaphor and training on metaphor coding procedure. The doctoral student only required training in established criteria for metaphor coding. Only those examples that received full agreement were included in the final corpus of analysis.

The implementation of this protocol resulted in the identification of 300 metaphorical expressions which were then manually annotated to ease the qualitative analysis of the most relevant metaphors underlying the conceptualization of menopause. The annotation scheme comprised 7 categories: (1) source domain, (2) target domain (different dimensions of the concept of menopause), (3) co-text, (4) source type (online clinics, commercial companies, health charities, activists’ associations, media (newspapers and TV), and academic websites), (5) link to source, (6) discourse function (descriptive/evaluative), and (7) axiological value (positive/negative).

The annotation plan was designed to facilitate the subsequent qualitative analysis in relation to the diverse aspects of menopause (i.e., duration, physical symptoms and effects, social consequences, etc.) that are highlighted by the different metaphorical mappings, as well as to the discourse functions of the metaphors identified in the study, and their axiological values.

4. ANALYSIS: MENOPAUSE METAPHORS

As advanced in section 2, throughout the 20th century and to our date the official discourse of menopause has fluctuated between the diametrically opposed positions represented by the biomedical and feminist communities. The former has highlighted those aspects of menopause that are relevant from a medical perspective, therefore adopting a metaphorical view of menopause as a health condition that needs to be treated. This discourse has been largely amplified by the pharmaceutical lobbies eager to find a market for their products (e.g., Hormone Replacement Treatments, vaginal gels and rings, etc.). At the other end of the spectrum, feminist groups have reacted to the medicalization of menopause by embracing several metaphors that focus on the positive effects of this phase of life and portrayed it as a liberation, a new beginning, or a sort of internal zest.

This section offers a qualitative analysis of the main four metaphors used by ordinary UK women in their conceptualization of menopause. As shall be explained in sections 4.1 to 4.4, they succeed in offering a rich characterization of this phase of life. The metaphors they use allow them to offer vivid descriptions of their feelings, as well as of the physical changes that they have undergone because of menopause, without limiting its characterization to either a negative health condition or a positive liberation force. Table 2 offers a summary of the metaphors found in the corpus and the number of occurrences for each of them:

Table 2. Menopause metaphors in the corpus of analysis

MENOPAUSE METAPHORS |

N |

MENOPAUSE IS A JOURNEY |

106 |

MENOPAUSE IS A FORCE |

65 |

DIVIDED SELF METAPHOR |

52 |

MENOPAUSE IS A STRUGGLE/FIGHT |

47 |

MENOPAUSE IS A CONTAINER |

12 |

MENOPAUSE IS A BUSINESS |

9 |

MENOPAUSE IS A GAME |

6 |

MENOPAUSE IS A THIEF |

2 |

MENOPAUSE IS A NON-CONFORMIST PERSON |

1 |

TOTAL |

300 |

As can be observed, there are four metaphors that stand up from the rest: menopause is a journey, menopause is a force, menopause is a struggle/fight, and the divided self metaphor. Unlike other more creative mappings (e.g. menopause is a game, menopause is a thief), these four metaphors are pervasive in the discourse of different women in our corpus, thus signaling their relevance in their conceptualization of menopause. Most testimonials make use of a combination of them, which seems only logical since each of them highlights different aspects of a multifaceted entity. Each of them is analyzed in the following sections in relation to their discourse functions (i.e. descriptive vs. evaluative) and their axiology (i.e. positive vs. negative).

4.1. Menopause is a journey

Journeys are a recursive source domain in many well-known conceptual metaphors involved in the conceptualization of notions that conform to the more abstract event-structure metaphor (e.g., life is a journey, love is a journey, etc., Lakoff, 1993). In a similar vein, in their testimonials, women often refer to their menopause as an unchosen, unexpected journey that often starts abruptly without prior notice. The journey metaphor is flexible enough to accommodate difference experiences of sudden, as well as smooth onsets of menopause:

- My perimenopause journey began in my mid 40’s in 2010, although I didn’t realise that was what it was. [My Menopause Centre]

- My journey began with a crash landing; I am discomfited to confess that at the age of 43, I had been diagnosed as perimenopausal. [The Menopause Charity]

Menopause is often depicted as a journey of self-discovery in which women embarked unprepared, thus alluding to the taboo nature of this process and the silence that has traditionally surrounded it:

- Ultimately, this journey of self-discovery led to me asking for a divorce […] I quickly realised that I was travelling into menopause without a guide. […] Surely there should be a leaflet that says: ‘Welcome to the first destination on your menopause holiday! Here’s some information to help you – what to pack, what you need.’ [My Menopause Centre]

The source domain of journeys also provides conceptual fabric to understand that menopause is not a unique event, but that it consists of several distinct phases which are conceptualized as landmarks or destinations along the journey, the first one being the perimenopause (example 1), followed by menopause (examples 2, 3, 4, and 5), and post menopause (example 6):

- When I talk about my ‘menopause holiday’, I’m describing my journey to many destinations along the way to menopause, with a lot of suitcases being packed and unpacked as I tried to decide what I needed to take with me. Now I can admit that, at first, I didn’t recognise any of these menopause destinations that I was fortunate enough to visit – and I know there are many more destinations to come. Alas, my HRT journey has ended abruptly while I undergo tests, but that’s another story. I still have many more destinations to visit on my menopause holiday, though my suitcases are now significantly better equipped. I wish I had known more when I first set off on my journey, but it isn’t too late – it never is. [The Menopause Charity]

- ‘I’m partway into a journey I didn’t know I’d begun. It started around 2015, and happened so slowly it took me around a year to work out what was happening. [My Menopause Centre]

- She sent me for blood tests and to my shock, the results showed I was way past menopause. [My Menopause Centre]

As in any journey, the traveler may be accompanied, and in the case of menopause there is the fixed company of hormonal changes which often take the steering wheel, hence making women lose control of their journey:

- I know what it’s like to live with your hormones in the driving seat. [My Menopause Centre]

The journey metaphor can take different specific configurations. It can be a long road trip or a sea crossing, a short but intense roller-coaster ride, a brief walk through muddy waters, an open air travel or a dark one through a tunnel, a surface trip or one that goes deep into the ground. Each of these journey metaphors allows women to verbalize their diverse menopausal experiences. Thus, the highly volatile emotional changes brought about by menopause find a vivid source domain in the roller-coaster metaphor:

- Personally, perimenopause has been an emotional rollercoaster. [British Nutrition Foundation]

The state of depression experienced by some women during their menopause is conceptualized as a downward trip into the depths. In these cases, the journey metaphor combines with the good is up/bad is down, and the container metaphors. Thus, menopause is conceptualized as a container which is the destination of a downward journey. Women reaching that destination are affected by its negative effects:

- I would never have imagined, three years ago, in the depths of the menopause… [Medical Prime]

Road trip metaphors can also help women express some of the negative aspects of the menopause journey, with hormonal unbalances understood as bumps along the road:

- There is still a long road ahead of me, but now I finally feel I have the right support in place for when I hit those hormonal bumps, which I inevitably I will. [The Menopause Charity]

The road trip metaphor often combines with the image of a tunnel which activates the correlation metaphor good is light/bad is darkness, thus highlighting the difficulties or rough patches of this journey:

- I’m coming out of the other side of menopause.[My Menopause Centre]

In yet other testimonials these difficulties are alternatively conceptualized as a tiresome walk through watery terrains or as sailing through a rough sea:

- Conversely at 47 I am wading through the perimenopause and my own confidence and certitudes can get railroaded by fears of anxiety or self doubt. [Health & Her]

- I finally started HRT mid-2017, but it was not plain sailing. [The Menopause Charity

- «navigating their own menopausal journeys.» [My Menopause Centre]

But not all trips are dark, rough, and bumpy. They can also be slow and pleasant, full of new landscapes and discoveries. Additionally, travelling is also culturally associated with a sense of liberation and a feeling of freedom. Therefore, this same source domain is useful in the conceptualization of menopause for those women whose experience of it is less traumatic or for those who choose to look on the bright side of this phase of their lives:

- When I was younger, there was always a finish line, but now I’m at the stage where there isn’t – this is my life and if I don’t do my best to be strong and healthy and grateful for what I’ve got, then I’m missing something. Instead of tearing down the motorway, I’m going down all the little side roads enjoying the view. And that’s hugely liberating.» [My Menopause Centre]

In these cases, the tunnel metaphor holds a promising destination once one gets through to the other side:

- […] and said that we could look forward to experiencing a ‘post-menopausal zest’ when we got through to the other side. I laughed when she said it and thought, that doesn’t seem very likely. But she was so right – now I’m there – insomnia gone, full of energy, no more night sweats, only very occasional flushes and a newfound confidence and stronger sense of self. I’m enjoying looking after myself during this stage of life. [The Guardian]

As shown in this section, the journey metaphor is useful in structuring women’s knowledge of the different phases they go through during menopause and their associated feelings. Thirty-seven out of one hundred and six (35%) of the instances of the menopause is a journey metaphor have a descriptive function that presents menopause as a process consisting in several stages (destinations) in a neutral fashion. The remaining sixty-nine examples of the menopause is a journey metaphor (65% of the total) have been found to be evaluative in nature. Although most of the latter (51 instances) offer a negative conceptualization of menopause as a long, bumpy road, such negative portrayal is also sometimes resisted by exploiting the metaphor in a more positive way (18 instances), and picturing some of the destinations of the journey as promising and desirable places (e.g., she feels now she has come through menopause, she has entered a new stage of 'freedom, self-knowledge, purpose and a life that’s no longer worrying about your fertility' [The Daily Mail]; Now I can admit that, at first, I didn’t recognize any of these menopause destinations that I was fortunate enough to visit [The Menopause Charity]). This metaphor, therefore, allows women to express both the negative, but also the positive aspects of the menopause journey.

4.2. Menopause is a force

The second most pervasive group of metaphors in our data involves the use of force schemata as source domains, as illustrated by the following testimonials:

- It’s great that there’s so much more talk about menopause now. If I had known right from the start what was happening it wouldn’t have hit me so hard, and that’s why I’m sharing my story. [My Menopause Centre]

- But then the menopause kicked in […] Then the deep menopausal symptoms hit and I thought I was going mad. [My Menopause Centre]

- so instead of building up slowly through perimenopause, my symptoms had all crashed in on me at once. [My Menopause Centre]

In examples (17) and (18), menopause is depicted as an agent exerting a sort of violent force on the woman (i.e., hit me so hard, kicked in). In (19) the exertion of the force is presented as the result of an involuntary action, nonetheless, impacting the woman in a destructive way (i.e., crashed in on me). Other words that activate the force frame are those of «impact» and «stunned» in examples (20) and (21), respectively:

- The menopause had an impact on me, it was incredibly physical. [U. of Leeds]

- During a routine gynae exam, another doctor suggested it might be menopause. I was completely stunned. [My Menopause Centre]

In both cases the metaphorical expression of menopause is part of a pattern of conceptual interaction with metonymic mappings. In (20), the impact is the effect of the exertion of the force (cause). Similarly, in (21) the state described by the adjective stunned is the effect of the exertion of the force (cause).

These examples are linguistic realizations of the menopause is a force metaphor, which may be considered as a subcase of the well-attested metaphor causes are forces (Dodge et al. 2015). The multiple symptoms of menopause act as the causing agents that exert negative forces onto women. As argued in Johnson (1987: 42), these metaphors have an experiential basis.

In order to survive as organisms, we must interact with our environment. All such causal interaction requires the exertion of force, either as we act upon other objects, or as we are acted upon by them. Therefore, in our efforts at comprehending our experience, structures of force come to play a central role. Since our experience is held together by forceful activity, our web of meanings is connected by the structures of such activity.

(Johnson, 1987: 42)

The gestalt structure for force, which underlies the conceptualization of menopause in examples (17)-(21), involves several features such as its interactional nature, its directionality, a particular path of motion, the involvement of an agent (origin) and a patient (target), the existence of different degrees of power or intensity, etc. As examples (17)-(21) illustrate, menopause is conceptualized as a powerful agent that exerts its force on women (targets). Most testimonials depict this force as one of high intensity through a careful choice of verbs (i.e., impact, hit, kicked in, stun, or crash in); as well as by means of intensifying adverbs (so hard, incredibly, completely). Thus, menopause is a forceful agent that exerts its effects on different aspects of a woman’s life, including her emotions, mental stability, career, family relations, and sexual interactions, among others.

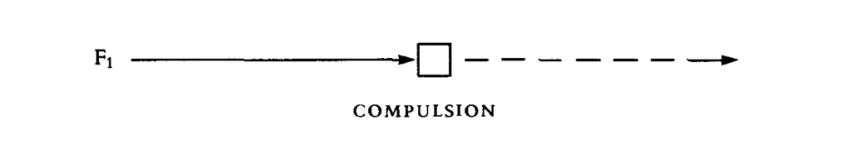

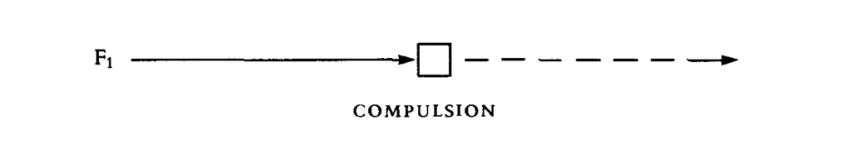

Johnson (1987: 45) distinguishes seven specific force schemata depending on the degree of intensity of the force and the existence of blockages to the exertion of the force (e.g., compulsion, blockage, counterforce, diversion, removal of restraint, enablement, attraction).

The metaphorical expressions found in the testimonials reflect several of these schemata. In some of them menopause is conceptualized as a compulsion schemata (i.e., as an irresistible force that comes from nowhere and is difficult to resist).

Figure 1. Compulsion Schema (Johnson, 1987)

Example (22) illustrates the compulsion schema, where menopause is an irresistible force that moves the woman out of her comfort zone:

- I’d never found it easy to talk about sex, but this had forced me out of my comfort zone, to communicate about what felt good for me, what worked and what didn’t. And Andrew listened, responded. [My Menopause Centre]

In some cases, the force exerted on the target can be iterative, consisting in several blows, as in example (23):

- This felt like one blow too many. I couldn’t stop thinking, why me? [My Menopause Centre]

Alternatively, menopause can also be metaphorically depicted as a destructive force that makes a woman’s life collapse:

- When your whole life collapses, you can start to treat it like Jenga. I picked the bits of my personality I liked, and decided to keep those and then tried to pull out the unhealthier aspects – like being too hard on myself – and work on those. […] It took a while to rebuild my life. [My Menopause Centre]

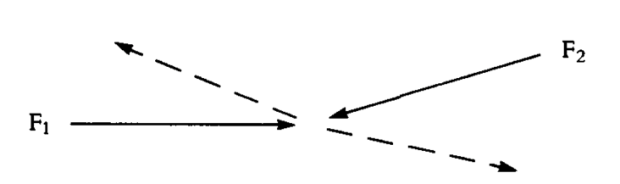

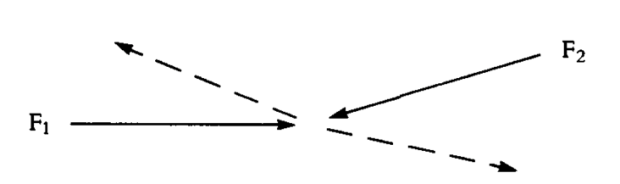

Other expressions illustrate the diversion schema, where one of the force vectors is diverted as the result of the causal interaction with a more powerful opposed force.

Figure 2. Diversion Schema (Johnson, 1987)

Examples (25) and (26) illustrate the diversion schema at work in the menopause metaphors. In (25) the woman’s love for her job collides with the symptoms of menopause which leads her off her desired path into relinquishing a potential new position. In (26) again, menopause takes a woman off her chosen path, forcing her to stay at home instead of attending her professional duties.

- In September, she will return to school as a part-time teacher, the symptoms of the menopause having forced her to step back from a role she loved. [The Guardian]

- […] and often forced me to stay home. [The Guardian]

Interestingly enough, in some cases, the force schema is inverted, and women are the ones that are conceptualized as forces, while menopause functions as a restraining force preventing their normal movements and functions. This is the case in example (27) which exemplifies the menopause is a cage metaphor, where menopause is represented as a container (i.e., a cage) that limits women’s freedom of action.

- I felt like a cage was constructing itself around me, putting up barriers to hinder me from functioning as before. [Health & Her]

In these cases, women’ feelings are also conceptualized as pressurized forces that need an outlet to avoid a metaphorical emotional burst:

- Life is still full-on, and I still have menopause symptoms, but I have an outlet now. Some days I’ll come to practice all stressed and nervous, but I’ll grab my bass and just let it all out. [My Menopause Centre]

The metaphors in this group have an evaluative function. As shown in examples (17) to (28), most of them (65 instances, 80%) depict menopause under a negative light, but forces need not be axiologically negative. In fact, 20% of the testimonials metaphorically portray menopause in terms of a compulsion schema that leads to positive consequences for the woman’s life. See examples (29) and (30).

- The changing hormones that gave me the oomph to start to question what was going on, and to start to put myself first. [My Menopause Centre]

- It forced me to start looking after myself after years of only looking after everyone else. [Health & Her]

This positive rendering of the menopause is a force metaphor is at the basis of other equally positive views of menopause that have also emerged in the testimonials under scrutiny. Among these resistance metaphors, there are some instances that present menopause as a liberating force (see example 31) that frees women from their reproductive role in society.

- It’s time to talk about the menopause… and freedom at last. The menopause comes,» says Kristin Scott Thomas’s character in Fleabag, «and it is the most wonderful fucking thing in the world.» «You’re free, no longer a slave, no longer a machine with parts. You’re just a person.» [The Guardian]

Example 32 also highlights this liberating effect of menopause by means of a metonymic mapping where «middle finger» stands for a non-conformist person, which then maps metaphorically onto the target domain of menopause. Both examples elaborate on the idea that menopausal experiences are forces that push women towards non-conformism and liberation from social impositions (i.e., motherhood, caring, beauty slavery, and eternal youth mandates, among others):

- I also educated myself about the hormonal changes I was going through. I learnt that as oestrogen declines, we have less of a tendency to want to nurture any offspring (which is one of oestrogen’s many roles!), plus we have a relative rise in testosterone, meaning we are more inclined to look after number one. In my work as a fitness trainer, I’d done some official learning around the menopause, and the trainer on the course called it ‘the middle finger years’, which really resonated with me! [My Menopause Centre]

4.3. The divided Self Metaphor

menopause is a journey and menopause is a force metaphors offer women a means to reflect and talk about the various phases and effects of menopause on their physical, emotional, social, and professional life. In addition, the divided person metaphor, which recurrently emerges in the examined testimonials, equips them with the essential conceptual framework to comprehend the nature and scope of its effects. It also aids in articulating their self-perceptions during this phase of life.

Lakoff's (1996) theory on the conceptual structure of the self establishes a system of conventional conceptual metaphors that seem to underlie our understanding of what a human being is. In this framework, a person is conceptualized as a composite entity comprised of a subject and a self, embodying what Lakoff refers to as the divided person metaphor. The subject represents the locus of reason, consciousness, and subjective experiences, whereas the self encompasses other aspects, including one's physical body, emotions, present and past social face, among others. Typically, the subject maintains control over the self, particularly when it resides in its expected position within or above the self. However, there are instances when the subject loses control over the self, resulting in a scenario where the latter lacks guidance (lost self metaphor). When incompatible aspects or interests within an individual come into conflict, they are metaphorically conceptualized as distinct individuals engaged in discord (termed "different selves") or as individuals occupying different locations (referred to as the split and scattered self metaphor). Many of the testimonials under scrutiny include metaphorical expressions that capture a disconnection between subject and self. In examples (33) to (35) women manifest this dissociation by expressing their incapacity to recognize their old selves.

- Chris would always tell me I looked lovely, but my changing body was an unavoidable reminder that I didn’t feel like myself anymore. [My Menopause Centre]

- I almost didn’t know myself anymore. [My Menopause Centre]

- That wasn’t me at all. [My Menopause Centre]

In (36), a woman elaborates the metaphor further to express that the subject has left the self and is now outside of it.

- I stopped feeling like ‘myself’. I couldn’t pin it down or put it into words, just a feeling that I was outside of myself or just not in touch with my old self. I really disliked my new self. Grumpy, short-tempered, anxious. [The Guardian

Example (37) conveys the same feeling of detachment by pointing to an absent subject which has been replaced by an alien, who is now in control of her body (self), and example (38) makes manifest that the subject does not like her new self which is represented by a changing body and new emotions, usually including a considerable amount of rage and emotional instability.

- She asked if it felt like an alien had taken over my body. And that’s exactly what it was like. [My Menopause Centre]

- I hated the person I saw staring back at me in the mirror. [The Menopause Charity]

The absence of a subject or the feeling of disconnection with it leaves the self without guidance, a lost self, as in example (39):

- I felt very different, as though I’d lost myself somewhere. I was feeling really hideous and not like myself. [The Menopause Charity]

In addition, a split self is not functional. Since subject and self are disconnected the human being cannot function properly. For this reason, most women openly manifest their desire to recover their old selves, and their happiness when this occurs, as illustrated in examples (40) to (42):

- I want to get through this. I want to be me again. [The Menopause Centre]

- Hormonal Replacement Treatment […] it’s helped me feel like myself again.

[The Menopause Centre]

- But more importantly, I feel like Vicky again. [The Menopause Centre]

The divided self metaphor is mainly used with an evaluative function (96% of the instances). As was the case with the conceptualizations of menopause as a journey or a force, the divided self metaphor is flexible enough to accommodate both the negative aspects of menopause (conceptualized as the loss of own’s self, 56% of the examples) and a positive representation of menopause (40% of the examples) as a process with a happy ending in which either the old self is rescued (examples 41 and 42) or alternatively, women come to terms and realize the advantages of their new selves (example 43):

- It’s a new you, and that’s wonderful. [Health & Her]

4.4. menopause is a struggle/fight

Given its conceptualization as a compulsion force that impacts women’s lives to the point of detaching them from their own selves, it is no surprise that the fourth most common metaphor at work in the testimonials under consideration is one that projects the source domain of war over the target domain of menopause. These examples are expressions of the more general disease treatment is a war metaphor (Dodge et al. 2015). Menopause is thus metaphorically portrayed as a fight against many diverse adversaries, such as one’s new self and the new body and negative feelings that come along with it, as illustrated in examples (44) and (45).

- ‘I’m nearly 40, I’m done for, doesn’t matter what I wear, I just always feel awful’. Then at some point I decided I’m going to fight against that feeling. [Health & Her]

- I’m also more able to cope with stuff, definitely a bit wiser, less likely to topple at the first hurdle. I still want to live and love and have fun. I’m just having to fight a bit harder to get there. [The Guardian]

Interestingly enough, women also use the war metaphor to express their feelings against the social pressure to medicalize the process of menopause (see example 46).

- My five-year struggle to avoid anti-depressants and get the right HRT. [The Menopause Charity]

In this metaphorical fight, women perceive themselves as the sufferers or victims:

- Louise said: «I suffered from night sweats, sometimes two to three times a night, and often five days a week. [U. of Leeds]

In turn, menopause is seen as the adversary who can take many different forms. In examples (48) and (49) it is alternatively personified as a silent assailant that appears without prior notice in her life or as a thief who steals relevant physical, emotional, and personal features of a woman, thus being responsible to a certain extent of the disconnection between subject and self, as shown in relation to the divided person metaphor.

- Menopause crept up on me with a variety of different symptoms that appeared out of nowhere. [The Menopause Charity]

- My friend jokes that she's been the victim of 'The Menopause Thief': he's taken her figure, quite a bit of her hair, her sex drive, and what she describes as 'my sense of myself as a woman'. I know what she means. He's taken quite a few bits of me, too. [The Daily Mail]

In those cases in which menopausal symptoms are mild, the fight is conceptualized as a game, in which women even have allies (e.g., hormonal replacement treatment), as in (50):

- HRT can be a total game-changer, so make sure you understand the benefits of it before you dismiss it like I had. [My Menopause Centre]

In other cases, especially those in which women have to face the worst menopausal symptoms (e.g., hot flushes, mental fog, rage fits, depression, etc.), the fight intensifies and is conceptualized as a full war:

- I tried to battle on but the hot flushes crept up over a year. [My Menopause Centre]

- When she was battling a host of other worsening menopausal symptoms. [The Menopause Charity]

The Menopause is a struggle/fight metaphor is eminently evaluative. All instances of this metaphor found in our data provide a negative portrayal of the menopause and of its various stages and effects.

As shown in this section, the analysis of the corpus data yields four main metaphorical mappings at work in UK women’s discourse about menopause (i.e., menopause is a journey, menopause is a force, the divided self metaphor, and menopause is a struggle/battle). As has been made manifest, most of the instances of these metaphors in our corpus describe the effects of menopause and evaluate them negatively. However, except for the menopause is a struggle/battle metaphor, the other three metaphorical renderings of menopause have also been shown to be flexible enough to accommodate both negative and positive portrayals of this stage of life. The divided self metaphor, in particular, yields a similar number of axiologically positive and negative instances. While those metaphors found in the biomedical literature focus exclusively on the negative aspects of menopause (Deutsch, 1945; Martin, 1987; Niland, 2010), and those found in feminist contexts tend to highlight what is positive about this process (Zeserson, 2001; Quental et al. 2023), three of the metaphors used by UK women identified in our corpus offer a richer view of this stage of their lives by depicting its hardships as well as its advantages.

5. CONCLUSIONS

UK women’s conceptualization of menopause involves mainly four conceptual metaphors: Menopause is a journey, Menopause is a force, The divided person metaphor, and Menopause is a struggle/fight. These conceptual mappings allow them to draw a faithful portrait of this phase of their lives, including its development, its different stages, and its negative and positive aspects.

Unlike biomedical discourse, ordinary women’s metaphorical talk about menopause does not make an extensive use of the Menopause is a health condition metaphor (Niland, 2010) or other conceptual mappings that involve its medicalization (i.e., Breakdown system and broken factory metaphors; Deutsch, 1945; Martin, 1987). The metaphorical conceptualization of menopause by ordinary UK women does not reflect an understanding of menopause in terms of an illness or health condition. Neither do they focus exclusively on a positive re-framing of menopause, as is the case with those metaphors stemming from sociological (feminist) perspectives (Menopause is a liberation/zest).

Our data shows that UK women resist those biased metaphors stemming from the biomedical and the feminist realms, and promote, through their use, alternative metaphorical conceptualizations of menopause which suit better its ambiguous nature and its varied effects on women. All metaphors at work in the testimonials under scrutiny reflect the relevance of this period of any woman’s life. Three of them (Menopause is a journey, Menopause is a force, The divided person metaphor) cover all aspects of the impact of menopause, both positive (liberating force), and negative (physical, emotional, social impact), in their lives. One of the positive effects of menopause is its capacity to push women towards non-conformism and liberation from social impositions (i.e., the motherhood, caring, beauty and eternal youth mandates). Further research should compare the metaphors arising in the language of UK women with those underlying the conceptualization of menopause by women belonging to other cultures in which some of those social mandates do not end with menopause (e.g., Mediterranean cultures in which women are expected to care for their relatives, including their elder, and also their grandchildren, long after they have entered their menopausal age).

REFERENCES

Bogo Jorgensen, Pernille (2020). Metaphor across genres and languages: How menopause is represented in Danish and American women's magazines and online discussion fora background. Researching and Applying Metaphor (RaAM) conference, 18-21 June. Norway University of Applied Sciences. Hamar, Norway.

Bogo Jorgensen, Pernille (2021). ‘It’s as natural as having a child’: How health ideologies surrounding menopause are expressed in women’s magazine. International Pragmatics conference (Ipra), 27 June to 2 July, Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW) Winterthur, Switzerland.

Bogo Jorgensen, Pernille (2022). ‘Menopause puts a strain on relationships’: Metaphor scenarios in discourses on menopause. Researching and Applying Metaphor (RaAM), 21-24 September. University of Bialystok, Poland.

Charlap, Cécile (2015). La fabrique de la ménopause. CNRS.

Charteris-Black, Jonathan (2004). Corpus approaches to Critical Metaphor Analysis. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230000612

Charteris-Black, Jonathan (2011). Politicians and rhetoric: The persuasive power of metaphor. 2nd Edition, Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230319899

de Lavalette, Kiki. Y. R., Andone, Corina, and Gerard J. Steen (2019). ‘I did not say that the government should be plundering anybody’s savings’: Resistance to metaphors expressing starting points in parliamentary debates. Journal of Language and Politics, 18(5), 718-738. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.18066.ren

Deutsch, Helene (1945). The psychology of women (Vol. 2). Grune and Stratton.

Dickson, Geri L. (1990). The metalanguage of menopause research. IMAGE: Journal of nursing scholarship, 22(3),168-173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1990.tb00202.x

Dodge, Ellen, Hong, Jisup, and Elise Stickles (2015). MetaNet: Deep semantic automatic metaphor analysis. In E. Shutova, B. B. Klebanov, & P. Lichtenstein (Eds.), Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Metaphor in NLP (pp. 40-49). NAACL HLT 2015.

Flint, Marcha (1975). The menopause: Reward or punishment? Psychosomatics, 16(4), 161-165. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(75)71183-0

Flusberg, Stephen J., Matlock, Teenie and Paul H. Thibodeau (2017). Metaphors for the war (or race) against climate change. Environmental Communication, 11(6), 769-783. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2017.1289111

Geddes, Linda (2022). It’s the great menopause gold rush. Guardian, 26 January. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2022/jan/26/from-vaginal-laser-treatment-to-spa-breaks-its-the-great-menopause-gold-rush (accessed 19 October 2023).

Gibbs, Raymond and Josie Siman (2021). How we resist metaphors. Language and Cognition, 13(4), 670-692. https://doi.org/10.1017/langcog.2021.18

Grady, Joseph E. (1997). Foundations of meaning: primary metaphors and primary scenes. PhD Dissertation. University of California.

Hart, Christopher (2010). Critical Discourse Analysis and Cognitive Science: New Perspectives on Immigration Discourse. Basingstoke: Palgrave

Hart, Christopher (2011). Legitimizing assertions and the logico-rhetorical module: evidence and epistemic vigilance in media discourse on immigration. Discourse Studies, 13(6), 751-814. https://doi.org/10.1177/146144561142136

Hart, Christopher (2019). Discourse. In E. Dąbrowska and D. Divjak (Eds.), Cognitive Linguistics - A survey of linguistic subfields (pp. 82-107). De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110626452

Hart, Christopher (2021). Animals vs. armies: Resistance to extreme metaphors in anti-immigration discourse. Journal of Language and Politics, 20(2), 226-253. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.20032.har

Hauser, David J. and Norbert Schwarz (2015). The war on prevention: Bellicose cancer metaphors hurt (some) prevention intentions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(1), 66-77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214557006

Hendricks, Rose K., Demjen, Zsófia, Semino, Elena and Lera Boroditsky (2018). Emotional implications of metaphor: consequences of metaphor framing for mindset about cancer. Metaphor and Symbol, 33(4), 267-279. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2018.1549835

Jin, Feng, Tao, MinFang, Teng, YinCheng, HongFang, Shao, ChangBing Li and Edward Mills (2015). Knowledge and attitude towards menopause and hormone replacement therapy in Chinese women. Gynecologic Obstetric Investigations 79(1), 40-5. https://doi.org/10.1159/000365172

Johnson, Mark (1987). The body in the mind. The bodily basis of meaning, imagination, and reasoning. University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, George (1987). Women, Fire and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind. University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, George (1993). A contemporary theory of metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and Thought (pp. 202-251). Cambridge University Press.

Lakoff, George (1996). Sorry I am not myself today: the metaphor system for conceptualizing the self. In G. Facounnier and E. Sweetser (Eds.), Spaces, worlds, and grammars. University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, George and Mark Johnson (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

Kabir, Md Ruhul and Kara Chan (2023). Menopausal experiences of women of Chinese ethnicity: A meta-ethnography. PLoS ONE, 18(9), e0289322. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0289322

Lazar, Amanda, Makoto Su, Norman, Bardzell, Jeffrey and Shaowen Bardzell (2019). Parting the Red Sea: Sociotechnical systems and lived experiences of menopause. CHI, 4-9, paper 480.

Martin, Emily (1987). The woman in the body: A cultural analysis of reproduction. Beacon.

Montagut, Marta and Carlota, M. Moragas-Fernández (2020). The European refugee crisis discourse in the Spanish Press: Mapping humanization and dehumanization frames through metaphors. International Journal of Communication, 14, 69-91.

Musolff, Andreas (2017). How metaphors can shape political reality: The figurative scenarios at the heart of Brexit. Papers in Language and Communication Studies, 1, 2-16.

Nerlich, Brigitte and Ilina Hellsten (2004). Genomics: shifts in metaphorical landscape between 2000 and 2003. New Genetics and Society, 23(3), 255-268. https://doi.org/10.1080/1463677042000305039

Niland, Patricia Ruth (2010). Metaphors of menopause in medicine. Master’s Dissertation. Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand.

Olza, Inés, Koller, Veronika, Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide, Pérez Sobrino, Paula and Elena Semino (2021). The #ReframeCovid initiative. From Twitter to society via metaphor. Metaphor and the Social World, 11(1), 98-20. https://doi.org/10.1075/msw.00013.olz

Orgard, Shani and Catherine Rottenberg (2023). The menopause moment: The rising visibility of ‘the change’ in UK news coverage. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494231159

Pérez-Hernández, Lorena and Paula Pérez Sobrino (2024). Consequences of metaphor frames for education: from beliefs to facts through language. Cognitive Studies/ Études cognitives, 24, 3074. https://doi.org/10.11649/cs.3074

Pérez-Sobrino, Paula, Semino, Elena, Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide, Koller, Veronika and Inés Olza (2022). Acting like a hedgehog in times of pandemic: Metaphorical creativity in the #ReframeCovid collection. Metaphor and Symbol, 37(2), 127-139. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2021.1949599

Porto, M. Dolores (2022) Water Metaphors and Evaluation of Syrian Migration: The Flow of Refugees in the Spanish Press. Metaphor and Symbol, 37(3), 252-267, http://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2021.1973871

Quental, Camila, Rojas Gaviria, Pilar and Céline del Bucchia (2023). The dialectic of (menopause) zest: Breaking the mold of organizational irrelevance. Gender, Work and Organization, 30(5), 1816-38. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.13017

Rosenblueth, Arturo, Wiener, Norbert and Julian Biegelow(1943). Behavior, purpose and teleology, Philosophy of Science,10, 18-24. https://doi.org/10.1086/286788

Santa Ana, Otto, Morán, Juan, and Cynthia Sánchez (1998). Awash under a Brown Tide: Immigration Metaphors in California Public and Print Media Discourse. Aztlán, 23(2), 137-177.

Santa Ana, Otto (2002). Brown tide rising: Metaphors of latinos in contemporary American public discourse. University of Texas Press.

Semino, Elena, Demmen, Jane and Zsófia Demjen (2016). An integrated approach to metaphor and framing in cognition, discourse, and practice, with an application to metaphors for cancer. Applied Linguistics (5), 1e22 https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amw028

Sontag, Susan (1979). Illness as Metaphor. Allen Lane.

Steen, Gerard, Dorst, Aletta G., Herrman, J.Berenike, Kaal, Anna, Krennmayr, Tina and Tryenje Pasma (2010). A Method for Linguistic Metaphor Identification: From MIP to MIPVU. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/celcr.14

Thibodeau, Paul H. and Lera Boroditsky (2011). Metaphors we think with: The role of metaphor in reasoning. PLoS ONE, 6(2), e16782.

Thibodeau, Paul H., Fleming, James and Maya Lannen (2019). Variation in methods for studying political metaphor: Comparing experiments and discourse analysis. In J. Perrez, M. Reuchamps and P. Thibodeau (Eds.), Variations in political metaphor (pp. 177-194). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/dapsac.85.08thi

Voda, Ann M. and Theresa George (1986). Menopause. In H.H. Werkey and J.J. Fitzpatrick (Eds.), Annual Review of Nursing Research, 4, 55-75. Springer. http://doi.org/10.1891/0739-6686.4.1.55

Wackers, Dunja, Y. M., Plug, José H. and Gerard J. Steen (2021). «For crying out loud, don’t call me a warrior»: Standpoints of resistance against violence metaphors for cancer. Journal of Pragmatics, 174: 68-77. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.12.021

Wackers, Dunja Y. M. and H. José Plug (2022). Countering Undesirable Implications of Violence Metaphors for Cancer through Metaphor Extension. Metaphor and Symbol, 37(1), 55-70. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2021.1948334

Wilbush, Joel (1982). Historical perspective: Climacteric expression and social context. Maturitas, 4, 195-205. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-5122(82)90049-4

Wodak, Ruth, and Michael Meyer (2009). Critical Discourse Analysis: History, Agenda, Theory, and Methodology. In R. Wodak and M. Meyer (Eds.). Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis (pp. 1-33). London: Sage.

Zeserson, Jan M. (2001). Chi no michi as metaphor: conversations with Japanese women about menopause. Anthropology & Medicine, 8(2-3), 177-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/13648470120101363

Notes

1 This publication is part of the R&D&i project PID2020-118349GB-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (Spain). [Volver]